Documents are CouchDB’s central data structure. To best understand and use CouchDB, you need to think in documents. This chapter walks you though the lifecycle of designing and saving a document. We’ll follow up by reading documents and aggregating and querying them with views. In the next section, you’ll see how CouchDB can also transform documents into other formats.

Documents are self-contained units of data. You might have heard the term record to describe something similar. Your data is usually made up of small native types such as integers and strings. Documents are the first level of abstraction over these native types. They provide some structure and logically group the primitive data. The height of a person might be encoded as an integer (176), but this integer is usually part of a larger structure that contains a label ("height": 176) and related data ({"name":"Chris", "height": 176}).

How many data items you put into your documents depends on your application and a bit on how you want to use views (later), but generally, a document roughly corresponds to an object instance in your programming language. Are you running an online shop? You will have items and sales and comments for your items. They all make good candidates for objects and subsequently documents.

Documents differ subtly from garden-variety objects, in that they usually have authors, and CRUD operations. Document-based software (like the word-processors and spreadsheets of yore) builds its storage model around saving documents, so that authors get back what they created. Similarly, in a CouchDB application, you may find yourself giving greater leeway to the presentation layer. If instead of adding timestamps to your data in a controller, you allow the user to control them, you get draft status and the ability to publish articles in the future for free. (By viewing published docs using an endkey of now.)

Document integrity… Validation functions are available so that you don’t have to worry about bad data causing errors in your system. Often in document-based software, the client application edits and manipulates the data, saving it back. As long as you give the user the document they asked you to save, they’ll be happy.

Say your users can comment on the item (“lovely book”); you have the option to store the comments as an array, on the item-document. This makes it trivial to find the item’s comments, but, as they say, “it doesn’t scale”. A popular item could have tens of comments, or even hundreds, or more.

Instead of storing a list on the item-document, in this case it may be better to model comments into a collection of documents. There are patterns for accessing collections, which CouchDB makes easy. You likely only want to show ten or twenty at a time, and provide “previous” and “next” links. By handling comments as individual entities, you can group them with views. A group could be the entire collection or slices of ten or twenty, sorted by the item they apply to, so it’s easy to grab the set you need.

A rule of thumb: Break up into documents everything that you will be handling separately in your application. Items are single, and comments are single, but you don’t need to break them into smaller pieces. Views are a convenient way to group your documents in meaningful ways. We’ll cover views for comments in Chapter 10: Related Comments with View Collation.

Let’s go through building our example application to show you in practice how to work with documents.

The first step in designing any application (once you know what the program is for and have the user-interaction nailed down) is deciding on the format it will use to represent and store data. Our example blog is written in JavaScript. A few lines back we said documents roughly represent your data objects, in this case there is a an exact correspondence. CouchDB borrowed the JSON data format from JavaScript; this allows us to directly use documents as native objects when programming. This is really convenient and leads to fewer problems down the road (if you ever worked with an ORM system, you might know what we are hinting at).

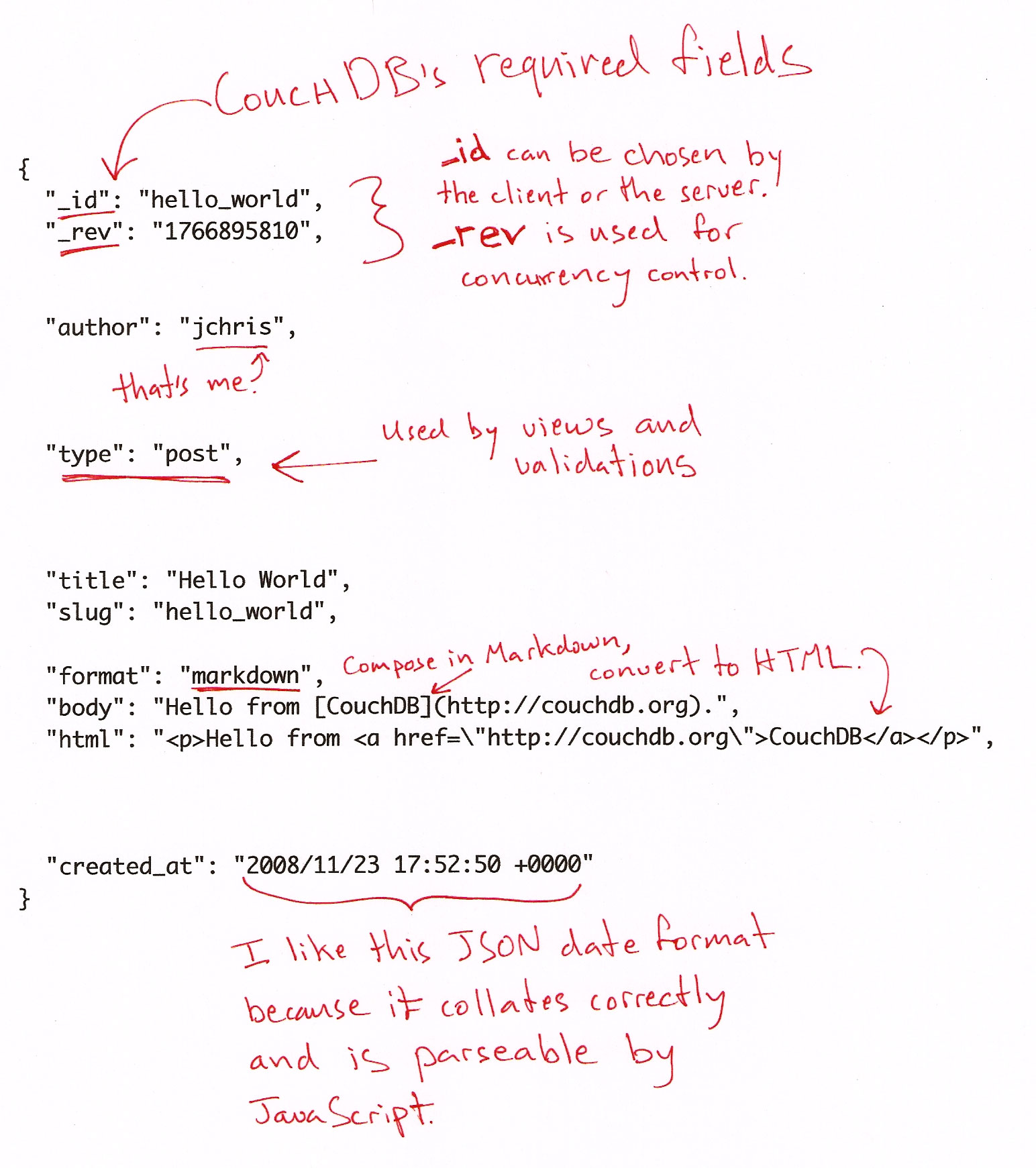

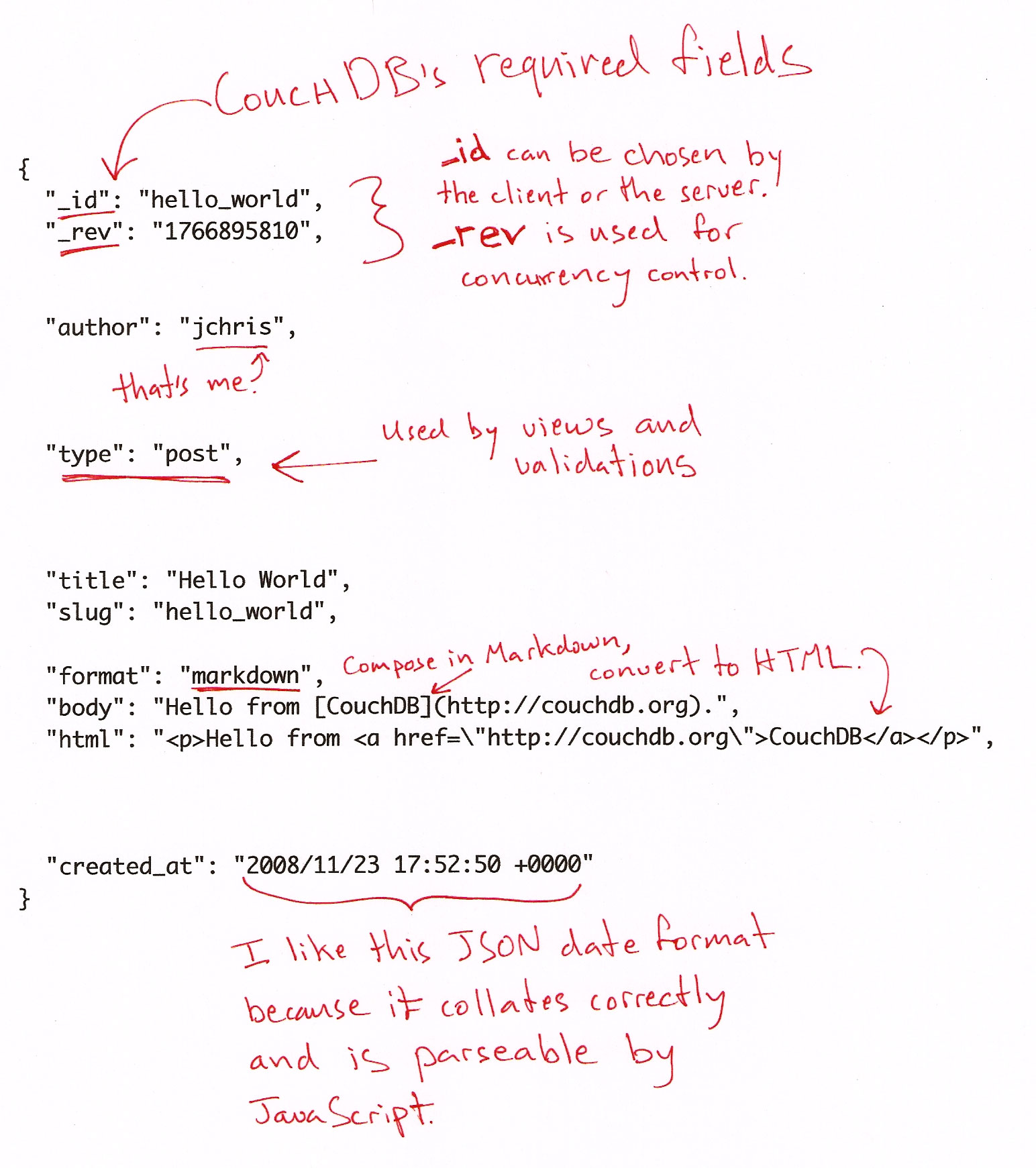

Let’s draft a JSON format for blog posts. We know we’ll need each post to have an author, a title, and a body. We know we’d like to use document ids to find documents, and that we’d also like to list them by creation date.

Figure: The JSON Post Format

{

"_id":"Hello-Sofa",

"_rev":"2-2143609722",

"type":"post",

"author":"jchris",

"title":"Hello Sofa",

"slug":"Hello-Sofa",

"tags":["example","blog post","json"],

"format":"markdown",

"body":"some markdown text",

"html":"<p>the html text</p>",

"created_at":"2009/05/25 06:10:40 +0000"

}

It should be pretty straightforward to see how JSON works. Curly braces ({}) wrap objects and objects are key-value lists. Keys are strings that are wrapped in double quotes ("") Finally, a value is a string, an integer, an object, or an array ([]). Keys and values are separated by a colon (:) and multiple keys and values by comma (,). That’s it. For a complete description of the JSON format see Appendix C.

Figure 1.1 shows a document that meets our requirements. The cool thing is: We just made it up on the spot. We didn’t go and define a schema, we didn’t prescribe how things should look like. We just created a document with whatever we just need. Now, requirements for objects change all the time during the development of an application. Coming up with a different document that meets new, evolved needs is just as easy.

Do I really look like a guy with a plan? You know what I am? I’m a dog chasing cars. I wouldn’t know what to do with one if I caught it. You know, I just… do things. The mob has plans, the cops have plans, Gordon’s got plans. You know, they’re schemers. Schemers trying to control their little worlds. I’m not a schemer. I try to show the schemers how pathetic their attempts to control things really are.

— The Joker, The Dark Knight

Let’s examine the document in a little more detail. The first two members (_id and _rev) are for CouchDB’s housekeeping and act as identification for a particular instance of a document. _id is easy: If I store something in CouchDB, it creates the _id and returns it to me. I can use the _id to build the URL where I can get my something back.

|

Your document’s _id defines the URL the document can be found under. Say you have a database movies. All documents can be found somewhere under the URL

/movies, but where exactly?

If you store a document with the _id Jabberwocky ({"_id":"Jabberwocky"}) into your movies database, it will be available under the URL /movies/Jabberwocky. So if you send a GET request to /movies/Jabberwocky, you will get back the JSON that makes up your document ({"_id":"Jabberwocky"}).

|

The _rev (or revision id) describes a version of a document. Each change creates a new document version (that again is self-contained), and updates the _rev. This becomes useful because when saving a document, you must provide an up to date _rev, so that CouchDB knows you’ve been working against the latest document version.

We touched on this in Chapter 2: Eventual Consistency. The revision id acts as a gatekeeper for writes to a document in CouchDB’s MVCC system. A document is a shared resource, many clients can read and write them at the same time. To make sure two writing clients don’t step on each others feet, each client must provide what it believes is the latest revision id of a document along with the proposed changes. If the on-disk revision id matches the provided _rev, CouchDB will accept the change. If it doesn’t, the update will be rejected. The client should read the latest version, integrate his changes and try saving again.

This mechanism ensures two things: A client can only overwrite a version it knows, and it can’t trip over changes made by other clients. This works without CouchDB having to manage explicit locks on any document. This ensures that no client has to wait for another client to complete any work. Updates are serialized, so CouchDB will never attempt to write documents faster than your disk can spin, and it also means that two mutually conflicting writes can’t be written at the same time.

Now on to the actual data. In the middle of the document you see

which is just an arbitrarily named key-value pair as far as CouchDB is concerned. For us, as we’re adding blog posts to Sofa, it has a little deeper meaning. To make writing views a little easier and to know how to validate differently structured documents, we use this trait so we know what kind of document we are dealing with. Again, this is purely by convention and you can make up your own, or you can infer the type of a document by its structure (“has an array with three elements”), we just thought this is easy to follow and we hope you agree.

The rest of the document’s members, author, title, slug, format, body and created_at are what we will be actually using and displaying in our application.

The first page we need to build, in order to get one of these blog entries into our post, is the interface for creating and editing posts.

Editing is more complex than just rendering posts for visitors to read, but that means once you’ve read this chapter, you’ll have seen most of the techniques we touch in the other chapters.

function(doc, req) {

// !json templates.edit

// !json blog

// !code vendor/couchapp/path.js

// !code vendor/couchapp/template.js

// we only show html

return template(templates.edit, {

doc : doc,

docid : toJSON((doc && doc._id) || null),

blog : blog,

assets : assetPath(),

index : listPath('index','recent-posts',{descending:true,limit:8})

});

}

The only missing piece of this puzzle is the HTML that it takes to save a document like this.

In your browser, visit http://127.0.0.1:5984/blog/_design/sofa/_show/edit and using your text editor, open the source file edit.html (or view source in your browser). Everything is ready to go, all we have to do is wire up CouchDB using in-page JavaScript.

needs updating for show

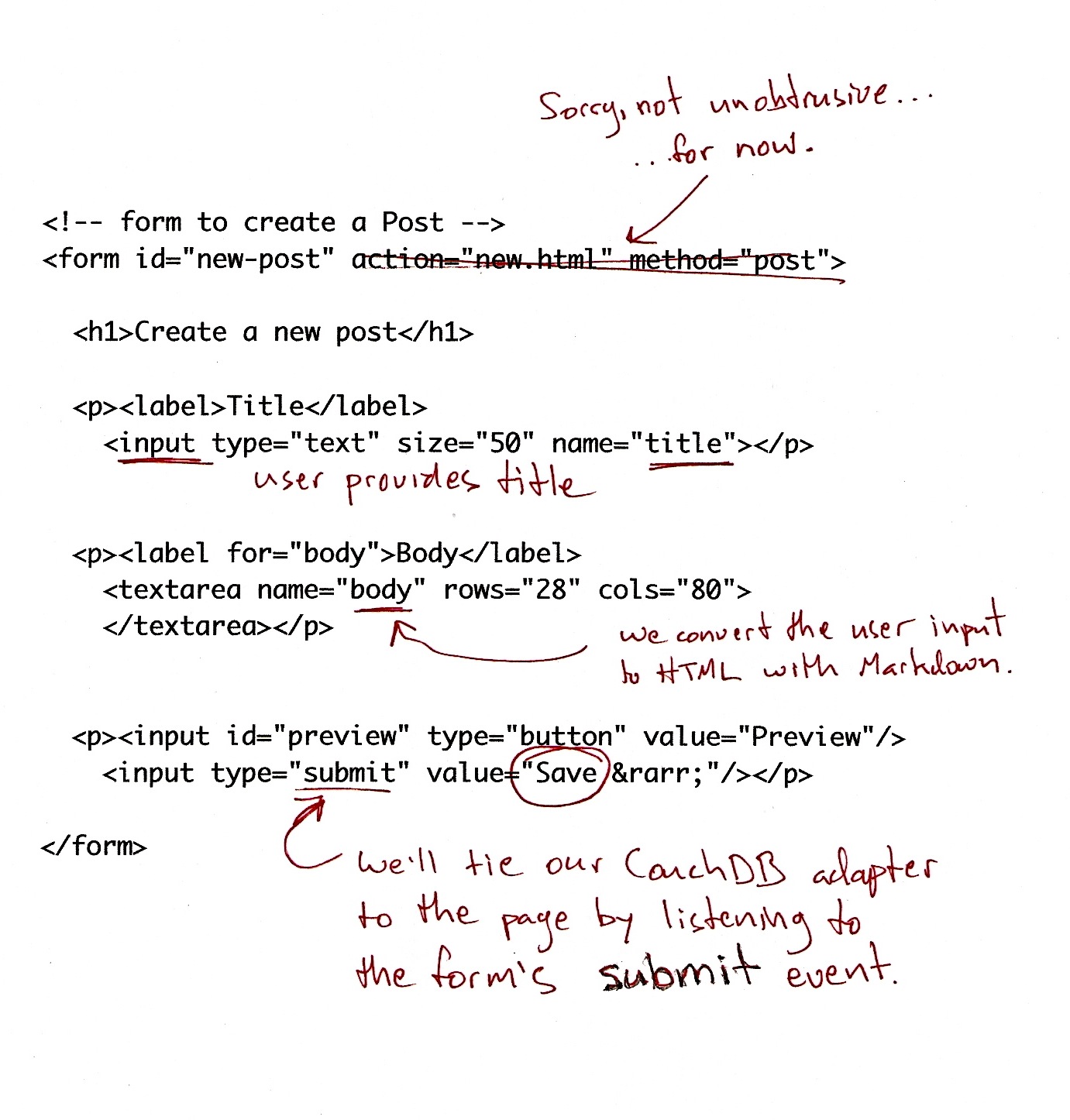

Figure: HTML listing for edit.html

<!-- form to create a Post -->

<form id="new-post" action="new.html" method="post">

<h1>Create a new post</h1>

<p><label>Title</label>

<input type="text" size="50" name="title"></p>

<p><label for="body">Body</label>

<textarea name="body" rows="28" cols="80">

</textarea></p>

<p><input id="preview" type="button" value="Preview"/>

<input type="submit" value="Save →"/></p>

</form>

When edit.html is complete it will be a complete blog post authoring tool, complete with Markdown format (and preview), and the ability to update existing blog posts.

We start with just a raw HTML document, containing a normal HTML form. We use JavaScript to convert user input into a JSON document and save it to CouchDB. In the spirit of focusing on CouchDB, we won’t dwell on the JavaScript here. It’s a combination of Sofa-specific application code and CouchApp’s JavaScript helpers. The basic story is that it watches for the user to click "Save", and then applies some callbacks to the document before sending it to CouchDB.

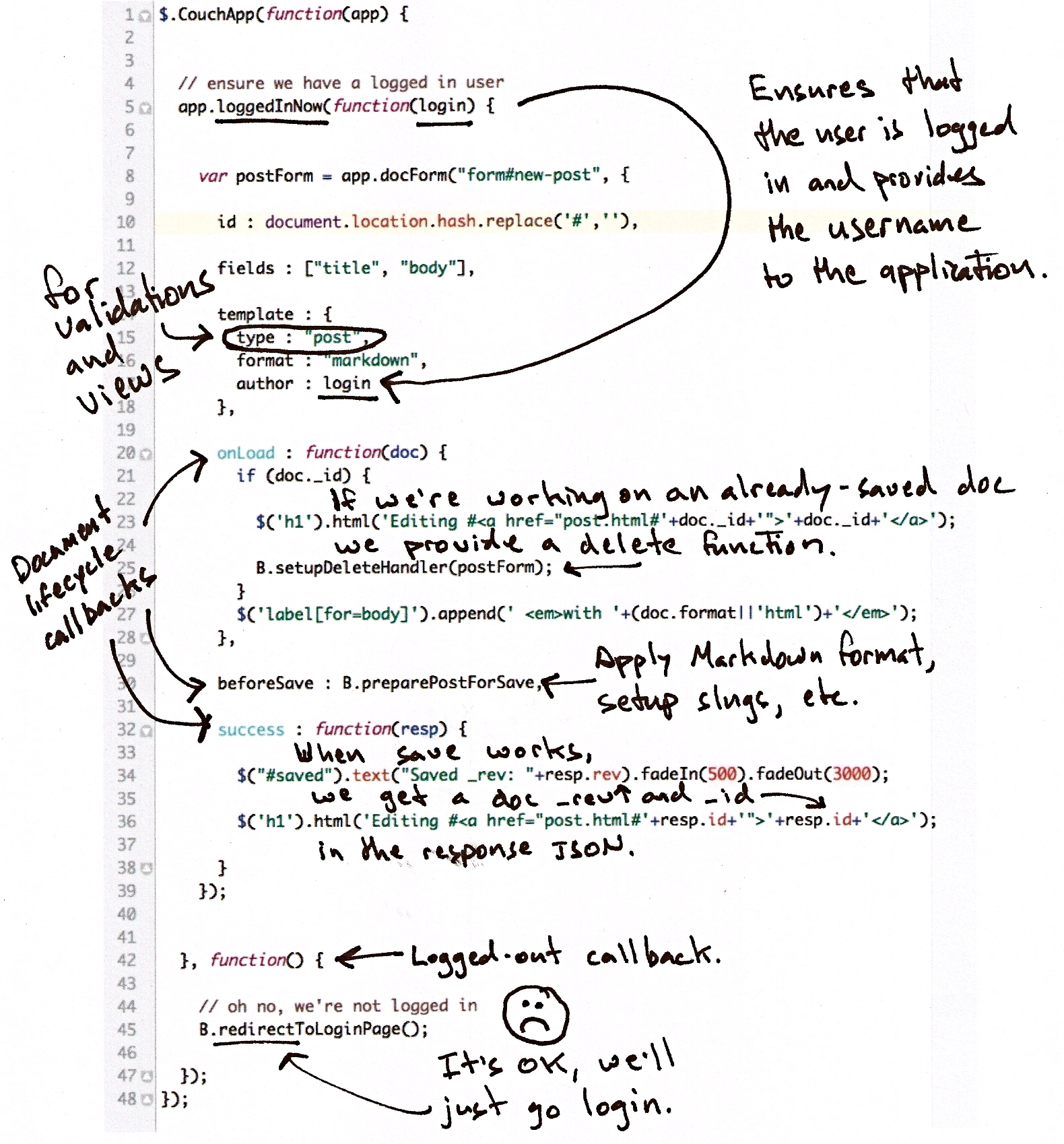

The JavaScript that drives blog post creation and editing centers around the HTML form from the previous figure. The CouchApp jQuery plugin provides some abstraction, so we don’t have to concern ourselves with the details of how the form is converted to a JSON document when the user hits the submit button.

$.CouchApp ensures that the user is logged in, and makes their information available to the application. We won’t go into the details of that now (as they are still in flux in CouchDB proper, Sofa’s authorization implementation is currently considered experimental.)

Figure: JavaScript callbacks for edit.html

$.CouchApp(function(app) {

// ensure we have a logged in user

app.ensureUser(function(user) {

var postForm = app.docForm("form#new-post", {

id : document.location.hash.replace('#',''),

fields : ["title", "body"],

template : {

type : "post",

format : "markdown",

author : user.name

},

onLoad : function(doc) {

if (doc._id) {

$('h1').html(

'Editing #<a href="post.html#'+doc._id+'">'

+ doc._id

+ '</a>'

);

}

$('label[for=body]')

.append(' <em>with '+(doc.format||'html')+'</em>');

},

beforeSave : B.preparePostForSave,

success : function(resp) {

$("#saved").text("Saved _rev: "+resp.rev)

.fadeIn(500).fadeOut(3000);

$('h1').html('Editing #<a href="post.html#'+resp.id+'">'+resp.id+'</a>');

}

});

}, function() {

// oh no, we're not logged in

app.go('login');

});

});

While trying not to get too deep into the JavaScript details, we’ll give a brief outline of what’s happening here. In the main function body, which executes once on page-load, we check to see that the user is logged in, then set up callbacks on the #new-post form.

When looking at the code, you see that app is an object passed into the page’s context, which has various helpers and methods, like docForm and loggedInNow.

CouchApp provides an API for mapping form fields to JSON objects. It also provides document-lifecycle callbacks, so the client application can do things like apply timestamps, render existing documents into the form, or do other processing when loading or editing the form.

Save your first post

Let’s see how this all works together! Fill out the form with some practice data, and hit "Save" to see a success response.

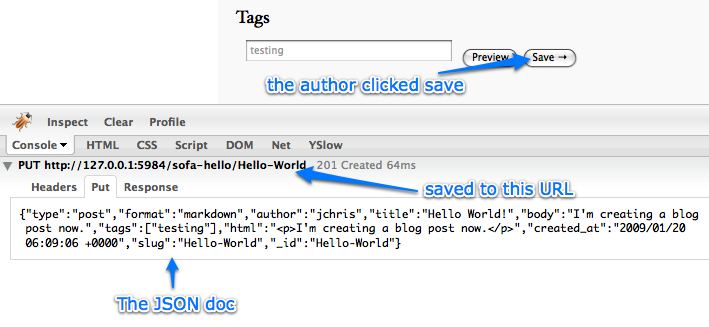

Screenshot: JSON over HTTP to save the blog post

The figure shows how JavaScript has used HTTP to PUT the document to a URL, constructed of the database name plus the document id. It also shows how the document is just sent as a JSON string in the body of the PUT request. If you were to GET the document URL, you’d see the same set of JSON data, with the addition of the _rev parameter as applied by CouchDB.

To see the JSON version of the document you’ve saved, you can also browse to it in Futon. Visit http://127.0.0.1:5984/_utils/database.html?blog/_all_docs and you should see a document with an id corresponding to the one you just saved. Click it to see what Sofa is sending to CouchDB.

Screenshot: Futon Document ViewThe document in Futon

We’ve covered how to design JSON formats for your application, how to enforce those designs with validation functions, the basics of how documents are saved, and maybe more than you wanted to know about the B-tree internals. In the next chapter we’ll show how to load documents from CouchDB and display them in the browser.