Transactions¶

Summary

- Transactions are proposals to update the ledger

- A transaction proposal will only be committed if:

- It doesn’t contain double-spends

- It is contractually valid

- It is signed by the required parties

Video¶

Overview¶

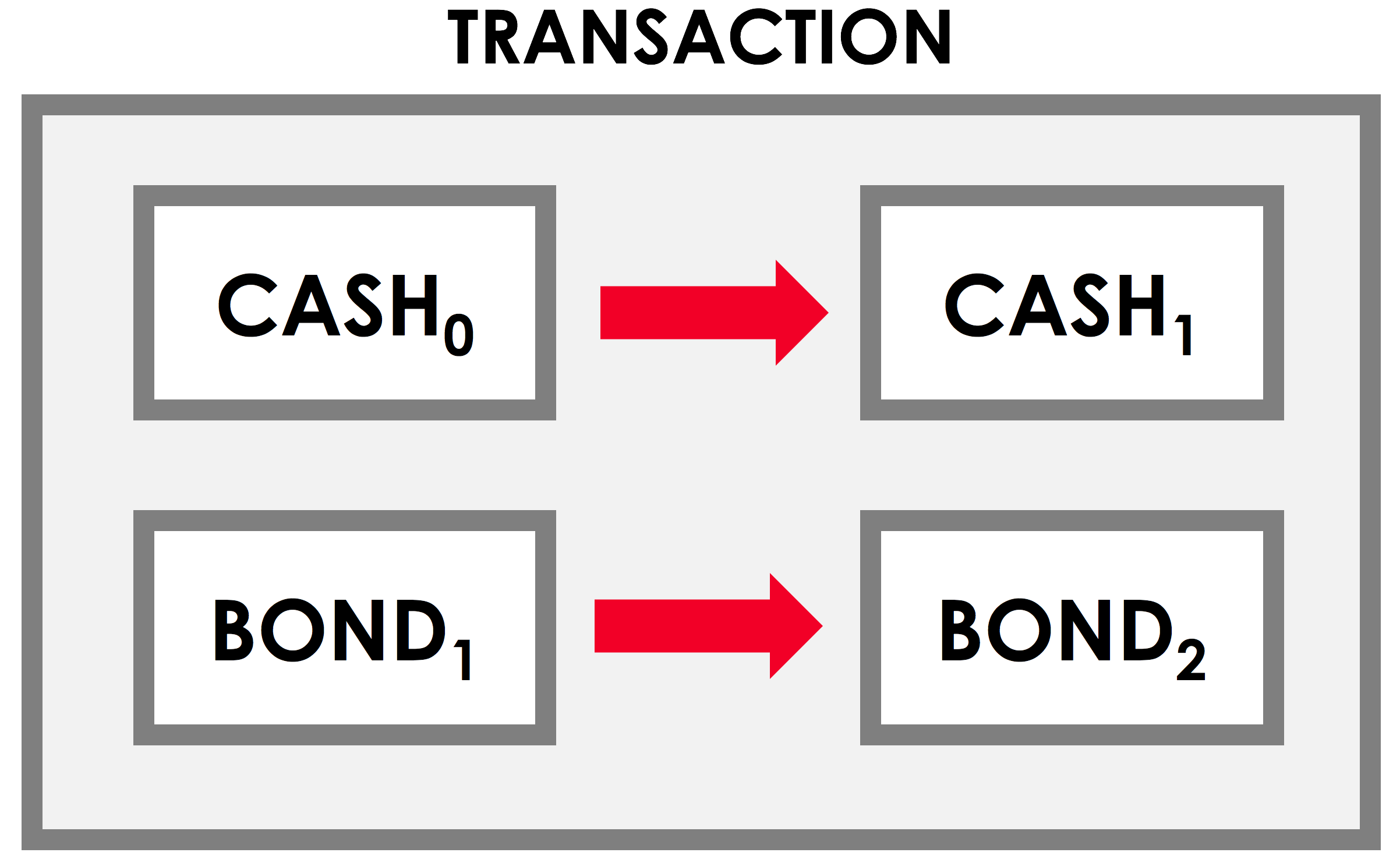

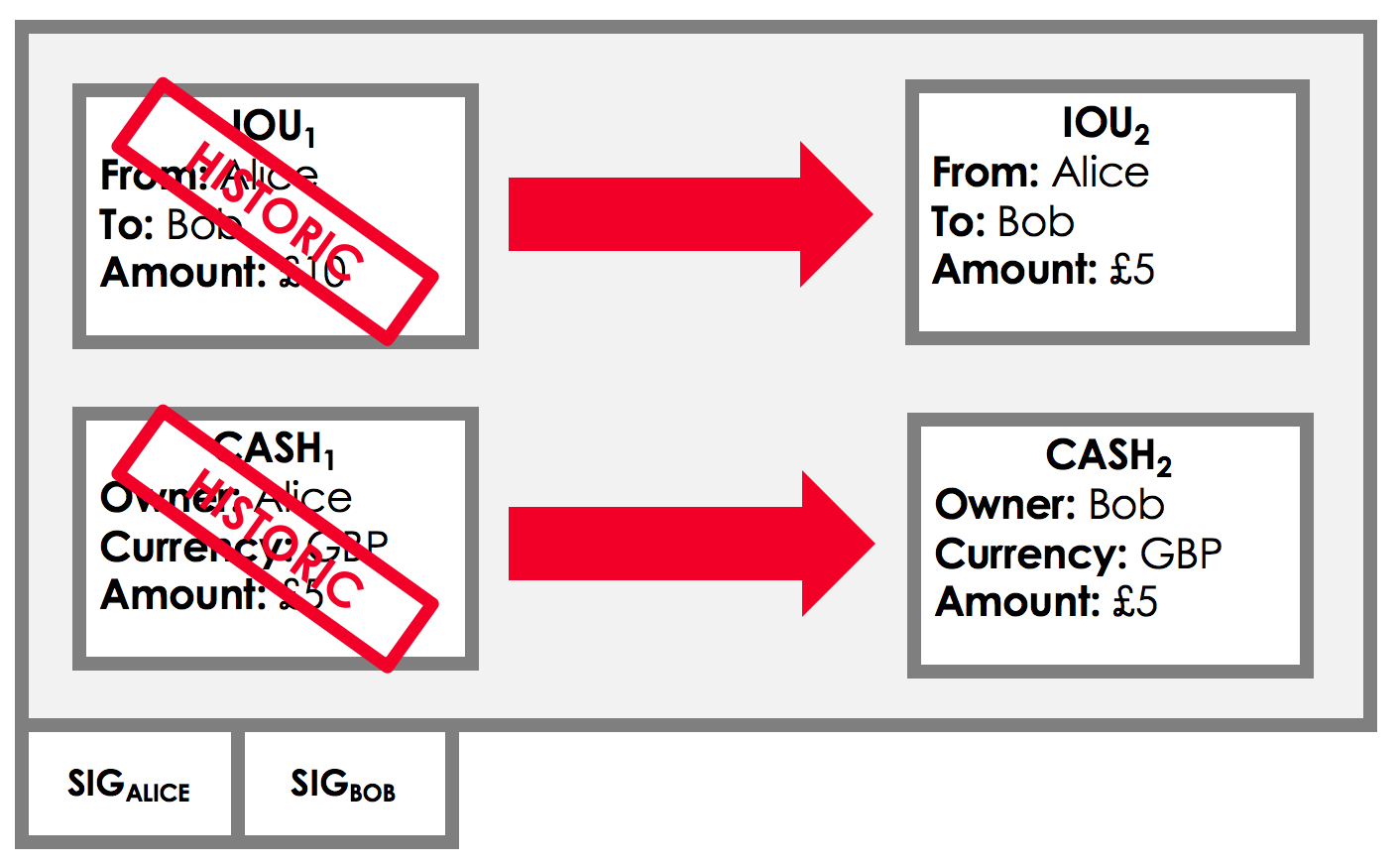

Corda uses a UTXO (unspent transaction output) model where every state on the ledger is immutable. The ledger evolves over time by applying transactions, which update the ledger by marking zero or more existing ledger states as historic (the inputs) and producing zero or more new ledger states (the outputs). Transactions represent a single link in the state sequences seen in States.

Here is an example of an update transaction, with two inputs and two outputs:

A transaction can contain any number of inputs and outputs of any type:

- They can include many different state types (e.g. both cash and bonds)

- They can be issuances (have zero inputs) or exits (have zero outputs)

- They can merge or split fungible assets (e.g. combining a $2 state and a $5 state into a $7 cash state)

Transactions are atomic: either all the transaction’s proposed changes are accepted, or none are.

There are two basic types of transactions:

- Notary-change transactions (used to change a state’s notary - see Notaries)

- General transactions (used for everything else)

Transaction chains¶

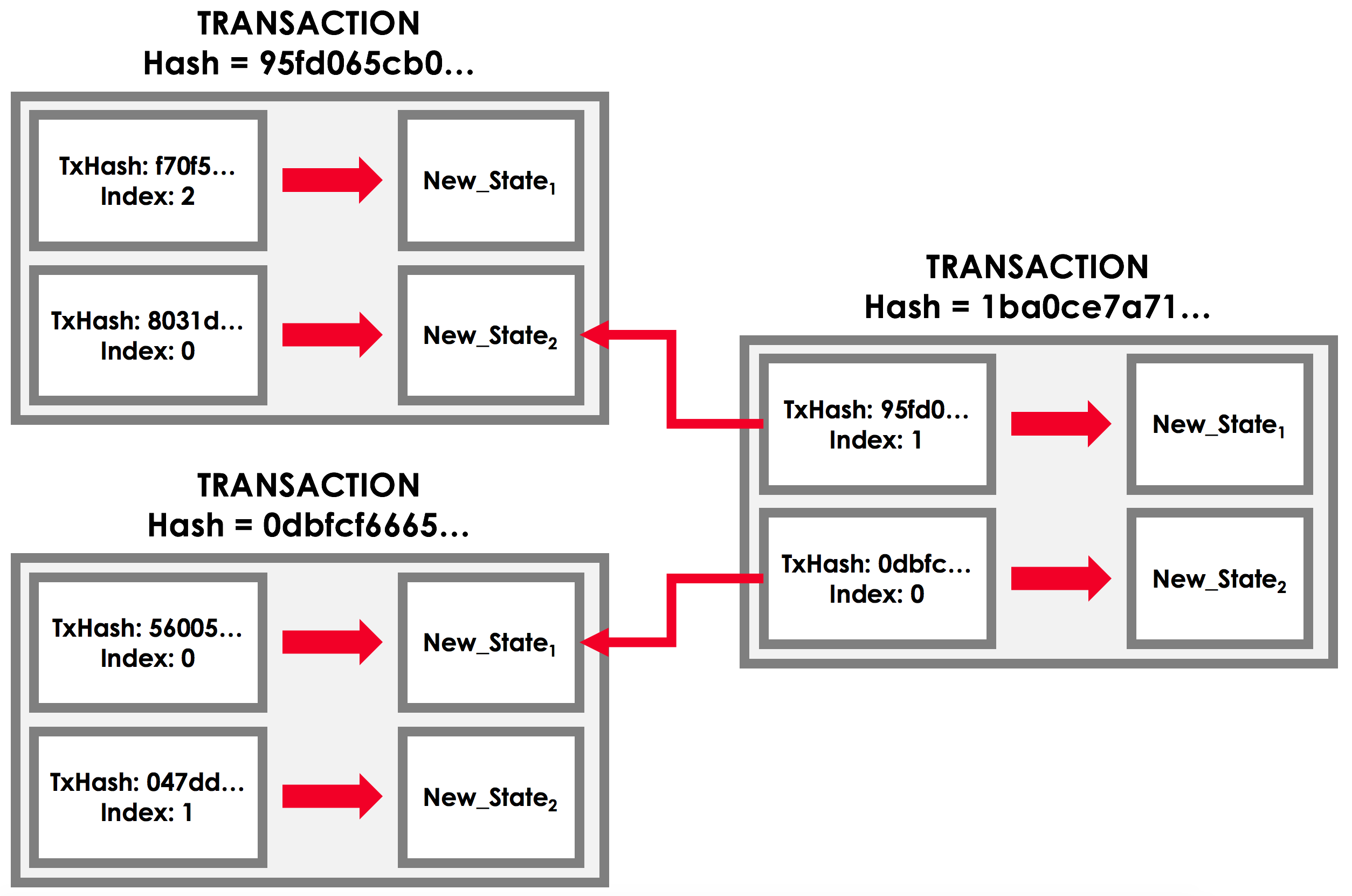

When creating a new transaction, the output states that the transaction will propose do not exist yet, and must therefore be created by the proposer(s) of the transaction. However, the input states already exist as the outputs of previous transactions. We therefore include them in the proposed transaction by reference.

These input states references are a combination of:

- The hash of the transaction that created the input

- The input’s index in the outputs of the previous transaction

This situation can be illustrated as follows:

These input state references link together transactions over time, forming what is known as a transaction chain.

Committing transactions¶

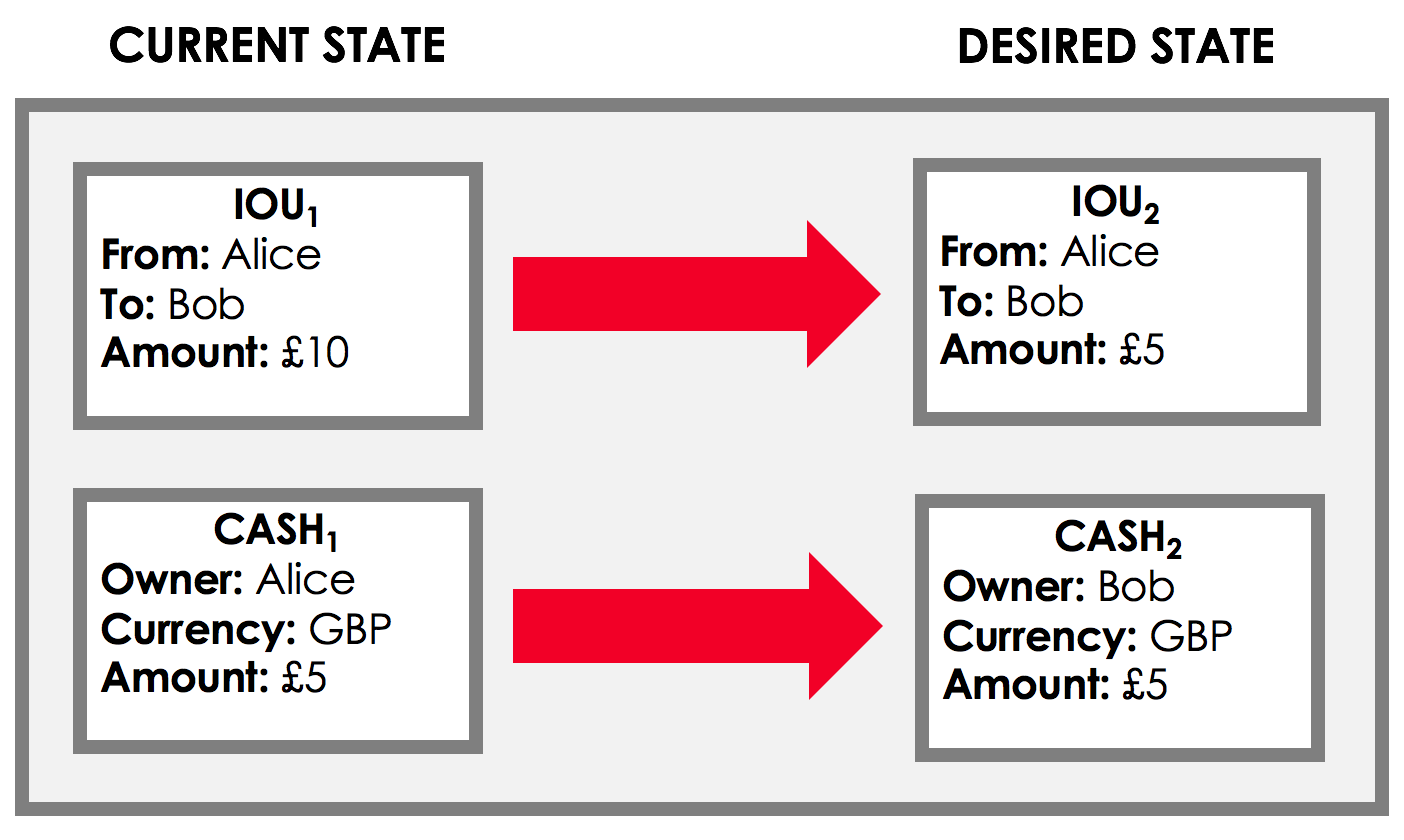

Initially, a transaction is just a proposal to update the ledger. It represents the future state of the ledger that is desired by the transaction builder(s):

To become reality, the transaction must receive signatures from all of the required signers (see Commands, below). Each required signer appends their signature to the transaction to indicate that they approve the proposal:

If all of the required signatures are gathered, the transaction becomes committed:

This means that:

- The transaction’s inputs are marked as historic, and cannot be used in any future transactions

- The transaction’s outputs become part of the current state of the ledger

Transaction validity¶

Each required signers should only sign the transaction if the following two conditions hold:

Transaction validity: For both the proposed transaction, and every transaction in the chain of transactions that created the current proposed transaction’s inputs:

- The transaction is digitally signed by all the required parties

- The transaction is contractually valid (see Contracts)

Transaction uniqueness: There exists no other committed transaction that has consumed any of the inputs to our proposed transaction (see Consensus)

If the transaction gathers all the required signatures but these conditions do not hold, the transaction’s outputs will not be valid, and will not be accepted as inputs to subsequent transactions.

Other transaction components¶

As well as input states and output states, transactions may contain:

- Commands

- Attachments

- Timestamps

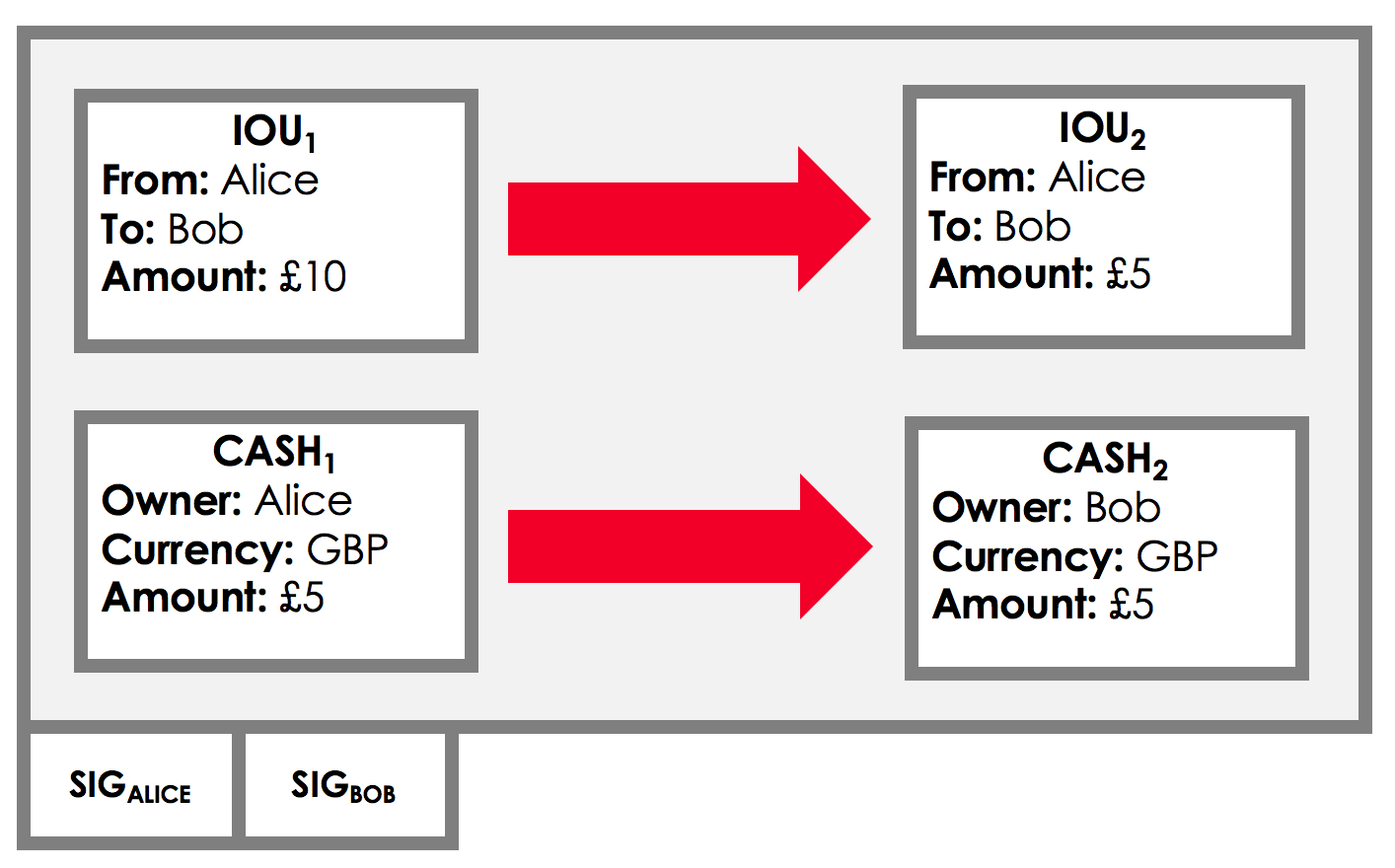

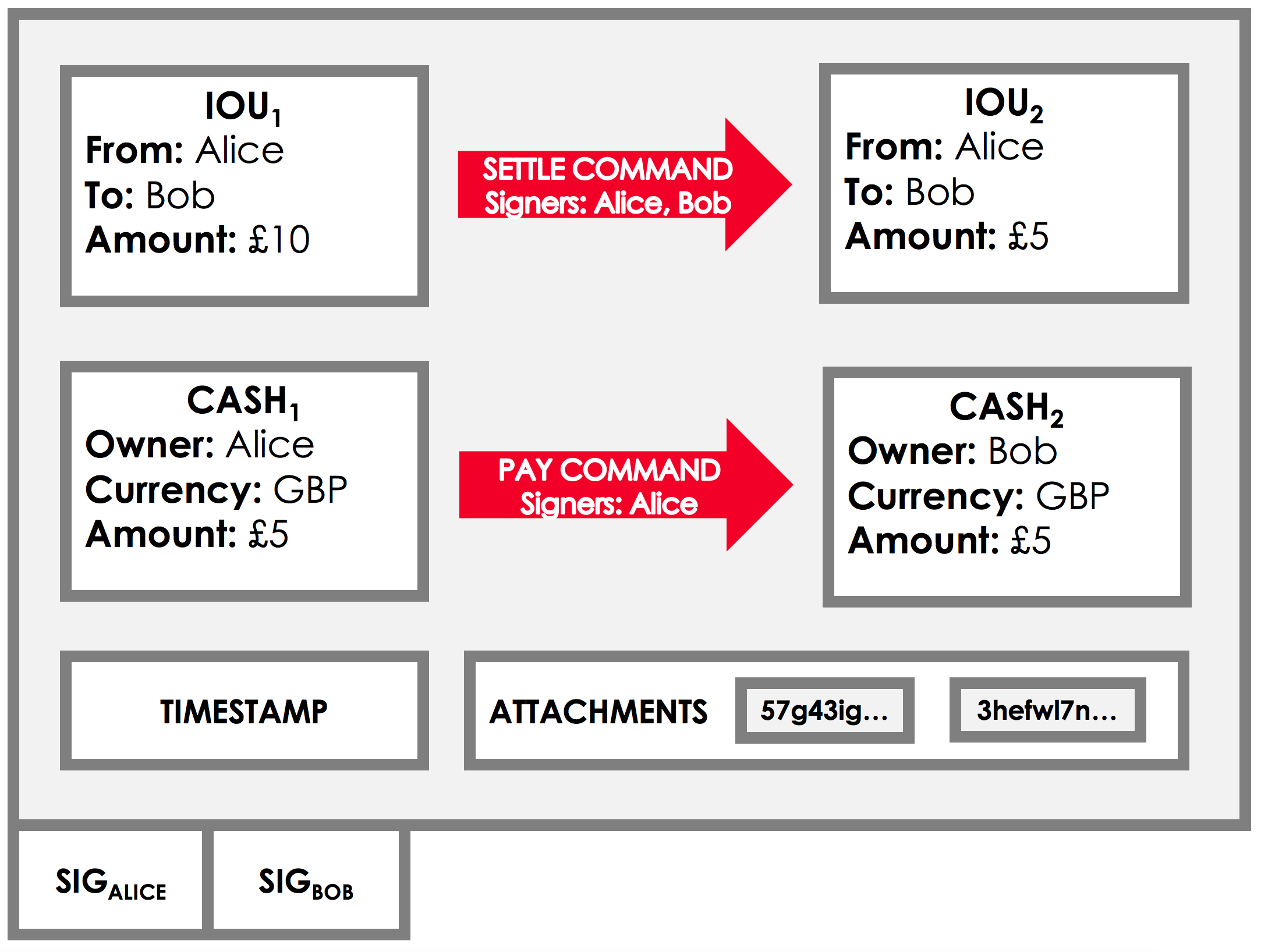

For example, a transaction where Alice pays off £5 of an IOU with Bob using a £5 cash payment, supported by two attachments and a timestamp, may look as follows:

We explore the role played by the remaining transaction components below.

Commands¶

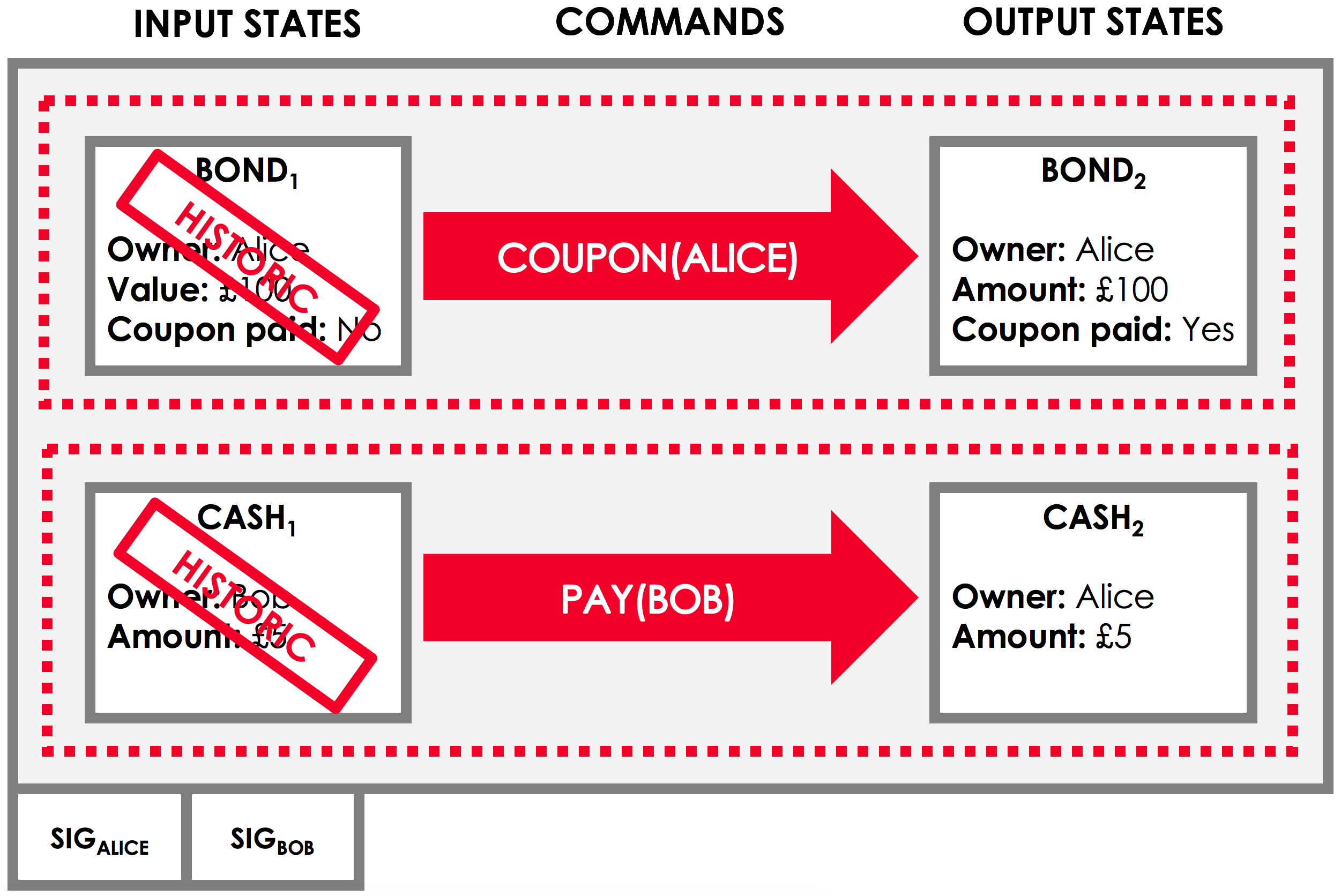

Suppose we have a transaction with a cash state and a bond state as inputs, and a cash state and a bond state as outputs. This transaction could represent two different scenarios:

- A bond purchase

- A coupon payment on a bond

We can imagine that we’d want to impose different rules on what constitutes a valid transaction depending on whether this is a purchase or a coupon payment. For example, in the case of a purchase, we would require a change in the bond’s current owner, whereas in the case of a coupon payment, we would require that the ownership of the bond does not change.

For this, we have commands. Including a command in a transaction allows us to indicate the transaction’s intent, affecting how we check the validity of the transaction.

Each command is also associated with a list of one or more signers. By taking the union of all the public keys listed in the commands, we get the list of the transaction’s required signers. In our example, we might imagine that:

- In a coupon payment on a bond, only the owner of the bond is required to sign

- In a cash payment, only the owner of the cash is required to sign

We can visualize this situation as follows:

Attachments¶

Sometimes, we have a large piece of data that can be reused across many different transactions. Some examples:

- A calendar of public holidays

- Supporting legal documentation

- A table of currency codes

For this use case, we have attachments. Each transaction can refer to zero or more attachments by hash. These attachments are ZIP/JAR files containing arbitrary content. The information in these files can then be used when checking the transaction’s validity.

Time-windows¶

In some cases, we want a transaction proposed to only be approved during a certain time-window. For example:

- An option can only be exercised after a certain date

- A bond may only be redeemed before its expiry date

In such cases, we can add a time-window to the transaction. Time-windows specify the time window during which the transaction can be committed. We discuss time-windows in the section on Time-windows.