Copyright © 1996 Addison-Wesley Longman, Inc

The second chapter of the book, The Design and Implementation of the 4.4BSD Operating System is excerpted here with the permission of the publisher. No part of it may be further reproduced or distributed without the publisher's express written permission. The rest of the book explores the concepts introduced in this chapter in incredible detail and is an excellent reference for anyone with an interest in BSD UNIX. More information about this book is available from the publisher, with whom you can also sign up to receive news of related titles. Information about BSD courses is available from Kirk McKusick.

- 2. Design Overview of 4.4BSD

- 2.1. 4.4BSD Facilities and the Kernel

- 2.2. Kernel Organization

- 2.3. Kernel Services

- 2.4. Process Management

- 2.5. Memory Management

- 2.6. I/O System

- 2.7. Filesystems

- 2.8. Filestores

- 2.9. Network Filesystem

- 2.10. Terminals

- 2.11. Interprocess Communication

- 2.12. Network Communication

- 2.13. Network Implementation

- 2.14. System Operation

- References

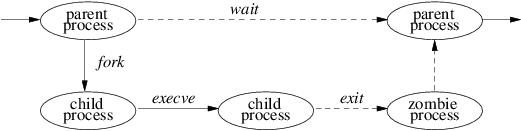

- 2.1. Process lifecycle

- 2.2. A small filesystem

- 2.1. 4.4BSD Facilities and the Kernel

- 2.2. Kernel Organization

- 2.3. Kernel Services

- 2.4. Process Management

- 2.5. Memory Management

- 2.6. I/O System

- 2.7. Filesystems

- 2.8. Filestores

- 2.9. Network Filesystem

- 2.10. Terminals

- 2.11. Interprocess Communication

- 2.12. Network Communication

- 2.13. Network Implementation

- 2.14. System Operation

- References

The 4.4BSD kernel provides four basic facilities: processes, a filesystem, communications, and system startup. This section outlines where each of these four basic services is described in this book.

Processes constitute a thread of control in an address space. Mechanisms for creating, terminating, and otherwise controlling processes are described in Chapter 4. The system multiplexes separate virtual-address spaces for each process; this memory management is discussed in Chapter 5.

The user interface to the filesystem and devices is similar; common aspects are discussed in Chapter 6. The filesystem is a set of named files, organized in a tree-structured hierarchy of directories, and of operations to manipulate them, as presented in Chapter 7. Files reside on physical media such as disks. 4.4BSD supports several organizations of data on the disk, as set forth in Chapter 8. Access to files on remote machines is the subject of Chapter 9. Terminals are used to access the system; their operation is the subject of Chapter 10.

Communication mechanisms provided by traditional UNIX systems include simplex reliable byte streams between related processes (see pipes, Section 11.1), and notification of exceptional events (see signals, Section 4.7). 4.4BSD also has a general interprocess-communication facility. This facility, described in Chapter 11, uses access mechanisms distinct from those of the filesystem, but, once a connection is set up, a process can access it as though it were a pipe. There is a general networking framework, discussed in Chapter 12, that is normally used as a layer underlying the IPC facility. Chapter 13 describes a particular networking implementation in detail.

Any real operating system has operational issues, such as how to start it running. Startup and operational issues are described in Chapter 14.

Sections 2.3 through 2.14 present introductory material related to Chapters 3 through 14. We shall define terms, mention basic system calls, and explore historical developments. Finally, we shall give the reasons for many major design decisions.

The kernel is the part of the system that runs in protected mode and mediates access by all user programs to the underlying hardware (e.g., CPU, disks, terminals, network links) and software constructs (e.g., filesystem, network protocols). The kernel provides the basic system facilities; it creates and manages processes, and provides functions to access the filesystem and communication facilities. These functions, called system calls appear to user processes as library subroutines. These system calls are the only interface that processes have to these facilities. Details of the system-call mechanism are given in Chapter 3, as are descriptions of several kernel mechanisms that do not execute as the direct result of a process doing a system call.

A kernel in traditional operating-system terminology, is a small nucleus of software that provides only the minimal facilities necessary for implementing additional operating-system services. In contemporary research operating systems -- such as Chorus [Rozier et al, 1988], Mach [Accetta et al, 1986], Tunis [Ewens et al, 1985], and the V Kernel [Cheriton, 1988] -- this division of functionality is more than just a logical one. Services such as filesystems and networking protocols are implemented as client application processes of the nucleus or kernel.

The 4.4BSD kernel is not partitioned into multiple processes. This basic design decision was made in the earliest versions of UNIX. The first two implementations by Ken Thompson had no memory mapping, and thus made no hardware-enforced distinction between user and kernel space [Ritchie, 1988]. A message-passing system could have been implemented as readily as the actually implemented model of kernel and user processes. The monolithic kernel was chosen for simplicity and performance. And the early kernels were small; the inclusion of facilities such as networking into the kernel has increased its size. The current trend in operating-systems research is to reduce the kernel size by placing such services in user space.

Users ordinarily interact with the system through a command-language interpreter, called a shell, and perhaps through additional user application programs. Such programs and the shell are implemented with processes. Details of such programs are beyond the scope of this book, which instead concentrates almost exclusively on the kernel.

Sections 2.3 and 2.4 describe the services provided by the 4.4BSD kernel, and give an overview of the latter's design. Later chapters describe the detailed design and implementation of these services as they appear in 4.4BSD.

In this section, we view the organization of the 4.4BSD kernel in two ways:

As a static body of software, categorized by the functionality offered by the modules that make up the kernel

By its dynamic operation, categorized according to the services provided to users

The largest part of the kernel implements the system services that applications access through system calls. In 4.4BSD, this software has been organized according to the following:

Basic kernel facilities: timer and system-clock handling, descriptor management, and process management

Memory-management support: paging and swapping

Generic system interfaces: the I/O, control, and multiplexing operations performed on descriptors

The filesystem: files, directories, pathname translation, file locking, and I/O buffer management

Terminal-handling support: the terminal-interface driver and terminal line disciplines

Interprocess-communication facilities: sockets

Support for network communication: communication protocols and generic network facilities, such as routing

| Category | Lines of code | Percentage of kernel |

|---|---|---|

| total machine independent | 162,617 | 80.4 |

| headers | 9,393 | 4.6 |

| initialization | 1,107 | 0.6 |

| kernel facilities | 8,793 | 4.4 |

| generic interfaces | 4,782 | 2.4 |

| interprocess communication | 4,540 | 2.2 |

| terminal handling | 3,911 | 1.9 |

| virtual memory | 11,813 | 5.8 |

| vnode management | 7,954 | 3.9 |

| filesystem naming | 6,550 | 3.2 |

| fast filestore | 4,365 | 2.2 |

| log-structure filestore | 4,337 | 2.1 |

| memory-based filestore | 645 | 0.3 |

| cd9660 filesystem | 4,177 | 2.1 |

| miscellaneous filesystems (10) | 12,695 | 6.3 |

| network filesystem | 17,199 | 8.5 |

| network communication | 8,630 | 4.3 |

| internet protocols | 11,984 | 5.9 |

| ISO protocols | 23,924 | 11.8 |

| X.25 protocols | 10,626 | 5.3 |

| XNS protocols | 5,192 | 2.6 |

Most of the software in these categories is machine independent and is portable across different hardware architectures.

The machine-dependent aspects of the kernel are isolated from the mainstream code. In particular, none of the machine-independent code contains conditional code for specific architecture. When an architecture-dependent action is needed, the machine-independent code calls an architecture-dependent function that is located in the machine-dependent code. The software that is machine dependent includes

Low-level system-startup actions

Trap and fault handling

Low-level manipulation of the run-time context of a process

Configuration and initialization of hardware devices

Run-time support for I/O devices

| Category | Lines of code | Percentage of kernel |

|---|---|---|

| total machine dependent | 39,634 | 19.6 |

| machine dependent headers | 1,562 | 0.8 |

| device driver headers | 3,495 | 1.7 |

| device driver source | 17,506 | 8.7 |

| virtual memory | 3,087 | 1.5 |

| other machine dependent | 6,287 | 3.1 |

| routines in assembly language | 3,014 | 1.5 |

| HP/UX compatibility | 4,683 | 2.3 |

Table 2.1, “Machine-independent software in the 4.4BSD kernel” summarizes the machine-independent software that constitutes the 4.4BSD kernel for the HP300. The numbers in column 2 are for lines of C source code, header files, and assembly language. Virtually all the software in the kernel is written in the C programming language; less than 2 percent is written in assembly language. As the statistics in Table 2.2, “Machine-dependent software for the HP300 in the 4.4BSD kernel” show, the machine-dependent software, excluding HP/UX and device support, accounts for a minuscule 6.9 percent of the kernel.

Only a small part of the kernel is devoted to initializing the system. This code is used when the system is bootstrapped into operation and is responsible for setting up the kernel hardware and software environment (see Chapter 14). Some operating systems (especially those with limited physical memory) discard or overlay the software that performs these functions after that software has been executed. The 4.4BSD kernel does not reclaim the memory used by the startup code because that memory space is barely 0.5 percent of the kernel resources used on a typical machine. Also, the startup code does not appear in one place in the kernel -- it is scattered throughout, and it usually appears in places logically associated with what is being initialized.

The boundary between the kernel- and user-level code is enforced by hardware-protection facilities provided by the underlying hardware. The kernel operates in a separate address space that is inaccessible to user processes. Privileged operations -- such as starting I/O and halting the central processing unit (CPU) -- are available to only the kernel. Applications request services from the kernel with system calls. System calls are used to cause the kernel to execute complicated operations, such as writing data to secondary storage, and simple operations, such as returning the current time of day. All system calls appear synchronous to applications: The application does not run while the kernel does the actions associated with a system call. The kernel may finish some operations associated with a system call after it has returned. For example, a write system call will copy the data to be written from the user process to a kernel buffer while the process waits, but will usually return from the system call before the kernel buffer is written to the disk.

A system call usually is implemented as a hardware trap that changes the CPU's execution mode and the current address-space mapping. Parameters supplied by users in system calls are validated by the kernel before being used. Such checking ensures the integrity of the system. All parameters passed into the kernel are copied into the kernel's address space, to ensure that validated parameters are not changed as a side effect of the system call. System-call results are returned by the kernel, either in hardware registers or by their values being copied to user-specified memory addresses. Like parameters passed into the kernel, addresses used for the return of results must be validated to ensure that they are part of an application's address space. If the kernel encounters an error while processing a system call, it returns an error code to the user. For the C programming language, this error code is stored in the global variable errno, and the function that executed the system call returns the value -1.

User applications and the kernel operate independently of each other. 4.4BSD does not store I/O control blocks or other operating-system-related data structures in the application's address space. Each user-level application is provided an independent address space in which it executes. The kernel makes most state changes, such as suspending a process while another is running, invisible to the processes involved.

4.4BSD supports a multitasking environment. Each task or thread of execution is termed a process. The context of a 4.4BSD process consists of user-level state, including the contents of its address space and the run-time environment, and kernel-level state, which includes scheduling parameters, resource controls, and identification information. The context includes everything used by the kernel in providing services for the process. Users can create processes, control the processes' execution, and receive notification when the processes' execution status changes. Every process is assigned a unique value, termed a process identifier (PID). This value is used by the kernel to identify a process when reporting status changes to a user, and by a user when referencing a process in a system call.

The kernel creates a process by duplicating the context of another process. The new process is termed a child process of the original parent process The context duplicated in process creation includes both the user-level execution state of the process and the process's system state managed by the kernel. Important components of the kernel state are described in Chapter 4.

The process lifecycle is depicted in Figure 2.1, “Process lifecycle”. A process may create a new process that is a copy of the original by using the fork system call. The fork call returns twice: once in the parent process, where the return value is the process identifier of the child, and once in the child process, where the return value is 0. The parent-child relationship induces a hierarchical structure on the set of processes in the system. The new process shares all its parent's resources, such as file descriptors, signal-handling status, and memory layout.

Although there are occasions when the new process is intended to be a copy of the parent, the loading and execution of a different program is a more useful and typical action. A process can overlay itself with the memory image of another program, passing to the newly created image a set of parameters, using the system call execve. One parameter is the name of a file whose contents are in a format recognized by the system -- either a binary-executable file or a file that causes the execution of a specified interpreter program to process its contents.

A process may terminate by executing an exit system call, sending 8 bits of exit status to its parent. If a process wants to communicate more than a single byte of information with its parent, it must either set up an interprocess-communication channel using pipes or sockets, or use an intermediate file. Interprocess communication is discussed extensively in Chapter 11.

A process can suspend execution until any of its child processes terminate using the wait system call, which returns the PID and exit status of the terminated child process. A parent process can arrange to be notified by a signal when a child process exits or terminates abnormally. Using the wait4 system call, the parent can retrieve information about the event that caused termination of the child process and about resources consumed by the process during its lifetime. If a process is orphaned because its parent exits before it is finished, then the kernel arranges for the child's exit status to be passed back to a special system process init: see Sections 3.1 and 14.6).

The details of how the kernel creates and destroys processes are given in Chapter 5.

Processes are scheduled for execution according to a process-priority parameter. This priority is managed by a kernel-based scheduling algorithm. Users can influence the scheduling of a process by specifying a parameter (nice) that weights the overall scheduling priority, but are still obligated to share the underlying CPU resources according to the kernel's scheduling policy.

The system defines a set of signals that may be delivered to a process. Signals in 4.4BSD are modeled after hardware interrupts. A process may specify a user-level subroutine to be a handler to which a signal should be delivered. When a signal is generated, it is blocked from further occurrence while it is being caught by the handler. Catching a signal involves saving the current process context and building a new one in which to run the handler. The signal is then delivered to the handler, which can either abort the process or return to the executing process (perhaps after setting a global variable). If the handler returns, the signal is unblocked and can be generated (and caught) again.

Alternatively, a process may specify that a signal is to be ignored, or that a default action, as determined by the kernel, is to be taken. The default action of certain signals is to terminate the process. This termination may be accompanied by creation of a core file that contains the current memory image of the process for use in postmortem debugging.

Some signals cannot be caught or ignored. These signals include SIGKILL, which kills runaway processes, and the job-control signal SIGSTOP.

A process may choose to have signals delivered on a special stack so that sophisticated software stack manipulations are possible. For example, a language supporting coroutines needs to provide a stack for each coroutine. The language run-time system can allocate these stacks by dividing up the single stack provided by 4.4BSD. If the kernel does not support a separate signal stack, the space allocated for each coroutine must be expanded by the amount of space required to catch a signal.

All signals have the same priority. If multiple signals are pending simultaneously, the order in which signals are delivered to a process is implementation specific. Signal handlers execute with the signal that caused their invocation to be blocked, but other signals may yet occur. Mechanisms are provided so that processes can protect critical sections of code against the occurrence of specified signals.

The detailed design and implementation of signals is described in Section 4.7.

Processes are organized into process groups. Process groups are used to control access to terminals and to provide a means of distributing signals to collections of related processes. A process inherits its process group from its parent process. Mechanisms are provided by the kernel to allow a process to alter its process group or the process group of its descendents. Creating a new process group is easy; the value of a new process group is ordinarily the process identifier of the creating process.

The group of processes in a process group is sometimes referred to as a job and is manipulated by high-level system software, such as the shell. A common kind of job created by a shell is a pipeline of several processes connected by pipes, such that the output of the first process is the input of the second, the output of the second is the input of the third, and so forth. The shell creates such a job by forking a process for each stage of the pipeline, then putting all those processes into a separate process group.

A user process can send a signal to each process in a process group, as well as to a single process. A process in a specific process group may receive software interrupts affecting the group, causing the group to suspend or resume execution, or to be interrupted or terminated.

A terminal has a process-group identifier assigned to it. This identifier is normally set to the identifier of a process group associated with the terminal. A job-control shell may create a number of process groups associated with the same terminal; the terminal is the controlling terminal for each process in these groups. A process may read from a descriptor for its controlling terminal only if the terminal's process-group identifier matches that of the process. If the identifiers do not match, the process will be blocked if it attempts to read from the terminal. By changing the process-group identifier of the terminal, a shell can arbitrate a terminal among several different jobs. This arbitration is called job control and is described, with process groups, in Section 4.8.

Just as a set of related processes can be collected into a process group, a set of process groups can be collected into a session. The main uses for sessions are to create an isolated environment for a daemon process and its children, and to collect together a user's login shell and the jobs that that shell spawns.

Each process has its own private address space. The address space is initially divided into three logical segments: text, data, and stack. The text segment is read-only and contains the machine instructions of a program. The data and stack segments are both readable and writable. The data segment contains the initialized and uninitialized data portions of a program, whereas the stack segment holds the application's run-time stack. On most machines, the stack segment is extended automatically by the kernel as the process executes. A process can expand or contract its data segment by making a system call, whereas a process can change the size of its text segment only when the segment's contents are overlaid with data from the filesystem, or when debugging takes place. The initial contents of the segments of a child process are duplicates of the segments of a parent process.

The entire contents of a process address space do not need to be resident for a process to execute. If a process references a part of its address space that is not resident in main memory, the system pages the necessary information into memory. When system resources are scarce, the system uses a two-level approach to maintain available resources. If a modest amount of memory is available, the system will take memory resources away from processes if these resources have not been used recently. Should there be a severe resource shortage, the system will resort to swapping the entire context of a process to secondary storage. The demand paging and swapping done by the system are effectively transparent to processes. A process may, however, advise the system about expected future memory utilization as a performance aid.

The support of large sparse address spaces, mapped files, and shared memory was a requirement for 4.2BSD. An interface was specified, called mmap, that allowed unrelated processes to request a shared mapping of a file into their address spaces. If multiple processes mapped the same file into their address spaces, changes to the file's portion of an address space by one process would be reflected in the area mapped by the other processes, as well as in the file itself. Ultimately, 4.2BSD was shipped without the mmap interface, because of pressure to make other features, such as networking, available.

Further development of the mmap interface continued during the work on 4.3BSD. Over 40 companies and research groups participated in the discussions leading to the revised architecture that was described in the Berkeley Software Architecture Manual [McKusick et al, 1994]. Several of the companies have implemented the revised interface [Gingell et al, 1987].

Once again, time pressure prevented 4.3BSD from providing an implementation of the interface. Although the latter could have been built into the existing 4.3BSD virtual-memory system, the developers decided not to put it in because that implementation was nearly 10 years old. Furthermore, the original virtual-memory design was based on the assumption that computer memories were small and expensive, whereas disks were locally connected, fast, large, and inexpensive. Thus, the virtual-memory system was designed to be frugal with its use of memory at the expense of generating extra disk traffic. In addition, the 4.3BSD implementation was riddled with VAX memory-management hardware dependencies that impeded its portability to other computer architectures. Finally, the virtual-memory system was not designed to support the tightly coupled multiprocessors that are becoming increasingly common and important today.

Attempts to improve the old implementation incrementally seemed doomed to failure. A completely new design, on the other hand, could take advantage of large memories, conserve disk transfers, and have the potential to run on multiprocessors. Consequently, the virtual-memory system was completely replaced in 4.4BSD. The 4.4BSD virtual-memory system is based on the Mach 2.0 VM system [Tevanian, 1987]. with updates from Mach 2.5 and Mach 3.0. It features efficient support for sharing, a clean separation of machine-independent and machine-dependent features, as well as (currently unused) multiprocessor support. Processes can map files anywhere in their address space. They can share parts of their address space by doing a shared mapping of the same file. Changes made by one process are visible in the address space of the other process, and also are written back to the file itself. Processes can also request private mappings of a file, which prevents any changes that they make from being visible to other processes mapping the file or being written back to the file itself.

Another issue with the virtual-memory system is the way that information is passed into the kernel when a system call is made. 4.4BSD always copies data from the process address space into a buffer in the kernel. For read or write operations that are transferring large quantities of data, doing the copy can be time consuming. An alternative to doing the copying is to remap the process memory into the kernel. The 4.4BSD kernel always copies the data for several reasons:

Often, the user data are not page aligned and are not a multiple of the hardware page length.

If the page is taken away from the process, it will no longer be able to reference that page. Some programs depend on the data remaining in the buffer even after those data have been written.

If the process is allowed to keep a copy of the page (as it is in current 4.4BSD semantics), the page must be made copy-on-write. A copy-on-write page is one that is protected against being written by being made read-only. If the process attempts to modify the page, the kernel gets a write fault. The kernel then makes a copy of the page that the process can modify. Unfortunately, the typical process will immediately try to write new data to its output buffer, forcing the data to be copied anyway.

When pages are remapped to new virtual-memory addresses, most memory-management hardware requires that the hardware address-translation cache be purged selectively. The cache purges are often slow. The net effect is that remapping is slower than copying for blocks of data less than 4 to 8 Kbyte.

The biggest incentives for memory mapping are the needs for accessing big files and for passing large quantities of data between processes. The mmap interface provides a way for both of these tasks to be done without copying.

The kernel often does allocations of memory that are needed for only the duration of a single system call. In a user process, such short-term memory would be allocated on the run-time stack. Because the kernel has a limited run-time stack, it is not feasible to allocate even moderate-sized blocks of memory on it. Consequently, such memory must be allocated through a more dynamic mechanism. For example, when the system must translate a pathname, it must allocate a 1-Kbyte buffer to hold the name. Other blocks of memory must be more persistent than a single system call, and thus could not be allocated on the stack even if there was space. An example is protocol-control blocks that remain throughout the duration of a network connection.

Demands for dynamic memory allocation in the kernel have increased as more services have been added. A generalized memory allocator reduces the complexity of writing code inside the kernel. Thus, the 4.4BSD kernel has a single memory allocator that can be used by any part of the system. It has an interface similar to the C library routines malloc and free that provide memory allocation to application programs [McKusick & Karels, 1988]. Like the C library interface, the allocation routine takes a parameter specifying the size of memory that is needed. The range of sizes for memory requests is not constrained; however, physical memory is allocated and is not paged. The free routine takes a pointer to the storage being freed, but does not require the size of the piece of memory being freed.

The basic model of the UNIX I/O system is a sequence of bytes that can be accessed either randomly or sequentially. There are no access methods and no control blocks in a typical UNIX user process.

Different programs expect various levels of structure, but the kernel does not impose structure on I/O. For instance, the convention for text files is lines of ASCII characters separated by a single newline character (the ASCII line-feed character), but the kernel knows nothing about this convention. For the purposes of most programs, the model is further simplified to being a stream of data bytes, or an I/O stream. It is this single common data form that makes the characteristic UNIX tool-based approach work [Kernighan & Pike, 1984]. An I/O stream from one program can be fed as input to almost any other program. (This kind of traditional UNIX I/O stream should not be confused with the Eighth Edition stream I/O system or with the System V, Release 3 STREAMS, both of which can be accessed as traditional I/O streams.)

UNIX processes use descriptors to reference I/O streams. Descriptors are small unsigned integers obtained from the open and socket system calls. The open system call takes as arguments the name of a file and a permission mode to specify whether the file should be open for reading or for writing, or for both. This system call also can be used to create a new, empty file. A read or write system call can be applied to a descriptor to transfer data. The close system call can be used to deallocate any descriptor.

Descriptors represent underlying objects supported by the kernel, and are created by system calls specific to the type of object. In 4.4BSD, three kinds of objects can be represented by descriptors: files, pipes, and sockets.

A file is a linear array of bytes with at least one name. A file exists until all its names are deleted explicitly and no process holds a descriptor for it. A process acquires a descriptor for a file by opening that file's name with the open system call. I/O devices are accessed as files.

A pipe is a linear array of bytes, as is a file, but it is used solely as an I/O stream, and it is unidirectional. It also has no name, and thus cannot be opened with open. Instead, it is created by the pipe system call, which returns two descriptors, one of which accepts input that is sent to the other descriptor reliably, without duplication, and in order. The system also supports a named pipe or FIFO. A FIFO has properties identical to a pipe, except that it appears in the filesystem; thus, it can be opened using the open system call. Two processes that wish to communicate each open the FIFO: One opens it for reading, the other for writing.

A socket is a transient object that is used for interprocess communication; it exists only as long as some process holds a descriptor referring to it. A socket is created by the socket system call, which returns a descriptor for it. There are different kinds of sockets that support various communication semantics, such as reliable delivery of data, preservation of message ordering, and preservation of message boundaries.

In systems before 4.2BSD, pipes were implemented using the filesystem; when sockets were introduced in 4.2BSD, pipes were reimplemented as sockets.

The kernel keeps for each process a descriptor table, which is a table that the kernel uses to translate the external representation of a descriptor into an internal representation. (The descriptor is merely an index into this table.) The descriptor table of a process is inherited from that process's parent, and thus access to the objects to which the descriptors refer also is inherited. The main ways that a process can obtain a descriptor are by opening or creation of an object, and by inheritance from the parent process. In addition, socket IPC allows passing of descriptors in messages between unrelated processes on the same machine.

Every valid descriptor has an associated file offset in bytes from the beginning of the object. Read and write operations start at this offset, which is updated after each data transfer. For objects that permit random access, the file offset also may be set with the lseek system call. Ordinary files permit random access, and some devices do, as well. Pipes and sockets do not.

When a process terminates, the kernel reclaims all the descriptors that were in use by that process. If the process was holding the final reference to an object, the object's manager is notified so that it can do any necessary cleanup actions, such as final deletion of a file or deallocation of a socket.

Most processes expect three descriptors to be open already when they start running. These descriptors are 0, 1, 2, more commonly known as standard input, standard output, and standard error, respectively. Usually, all three are associated with the user's terminal by the login process (see Section 14.6) and are inherited through fork and exec by processes run by the user. Thus, a program can read what the user types by reading standard input, and the program can send output to the user's screen by writing to standard output. The standard error descriptor also is open for writing and is used for error output, whereas standard output is used for ordinary output.

These (and other) descriptors can be mapped to objects other than the terminal; such mapping is called I/O redirection, and all the standard shells permit users to do it. The shell can direct the output of a program to a file by closing descriptor 1 (standard output) and opening the desired output file to produce a new descriptor 1. It can similarly redirect standard input to come from a file by closing descriptor 0 and opening the file.

Pipes allow the output of one program to be input to another program without rewriting or even relinking of either program. Instead of descriptor 1 (standard output) of the source program being set up to write to the terminal, it is set up to be the input descriptor of a pipe. Similarly, descriptor 0 (standard input) of the sink program is set up to reference the output of the pipe, instead of the terminal keyboard. The resulting set of two processes and the connecting pipe is known as a pipeline. Pipelines can be arbitrarily long series of processes connected by pipes.

The open, pipe, and socket system calls produce new descriptors with the lowest unused number usable for a descriptor. For pipelines to work, some mechanism must be provided to map such descriptors into 0 and 1. The dup system call creates a copy of a descriptor that points to the same file-table entry. The new descriptor is also the lowest unused one, but if the desired descriptor is closed first, dup can be used to do the desired mapping. Care is required, however: If descriptor 1 is desired, and descriptor 0 happens also to have been closed, descriptor 0 will be the result. To avoid this problem, the system provides the dup2 system call; it is like dup, but it takes an additional argument specifying the number of the desired descriptor (if the desired descriptor was already open, dup2 closes it before reusing it).

Hardware devices have filenames, and may be accessed by the user via the same system calls used for regular files. The kernel can distinguish a device special file or special file, and can determine to what device it refers, but most processes do not need to make this determination. Terminals, printers, and tape drives are all accessed as though they were streams of bytes, like 4.4BSD disk files. Thus, device dependencies and peculiarities are kept in the kernel as much as possible, and even in the kernel most of them are segregated in the device drivers.

Hardware devices can be categorized as either structured or unstructured; they are known as block or character devices, respectively. Processes typically access devices through special files in the filesystem. I/O operations to these files are handled by kernel-resident software modules termed device drivers. Most network-communication hardware devices are accessible through only the interprocess-communication facilities, and do not have special files in the filesystem name space, because the raw-socket interface provides a more natural interface than does a special file.

Structured or block devices are typified by disks and magnetic tapes, and include most random-access devices. The kernel supports read-modify-write-type buffering actions on block-oriented structured devices to allow the latter to be read and written in a totally random byte-addressed fashion, like regular files. Filesystems are created on block devices.

Unstructured devices are those devices that do not support a block structure. Familiar unstructured devices are communication lines, raster plotters, and unbuffered magnetic tapes and disks. Unstructured devices typically support large block I/O transfers.

Unstructured files are called character devices because the first of these to be implemented were terminal device drivers. The kernel interface to the driver for these devices proved convenient for other devices that were not block structured.

Device special files are created by the mknod system call. There is an additional system call, ioctl, for manipulating the underlying device parameters of special files. The operations that can be done differ for each device. This system call allows the special characteristics of devices to be accessed, rather than overloading the semantics of other system calls. For example, there is an ioctl on a tape drive to write an end-of-tape mark, instead of there being a special or modified version of write.

The 4.2BSD kernel introduced an IPC mechanism more flexible than pipes, based on sockets. A socket is an endpoint of communication referred to by a descriptor, just like a file or a pipe. Two processes can each create a socket, and then connect those two endpoints to produce a reliable byte stream. Once connected, the descriptors for the sockets can be read or written by processes, just as the latter would do with a pipe. The transparency of sockets allows the kernel to redirect the output of one process to the input of another process residing on another machine. A major difference between pipes and sockets is that pipes require a common parent process to set up the communications channel. A connection between sockets can be set up by two unrelated processes, possibly residing on different machines.

System V provides local interprocess communication through FIFOs (also known as named pipes). FIFOs appear as an object in the filesystem that unrelated processes can open and send data through in the same way as they would communicate through a pipe. Thus, FIFOs do not require a common parent to set them up; they can be connected after a pair of processes are up and running. Unlike sockets, FIFOs can be used on only a local machine; they cannot be used to communicate between processes on different machines. FIFOs are implemented in 4.4BSD only because they are required by the POSIX.1 standard. Their functionality is a subset of the socket interface.

The socket mechanism requires extensions to the traditional UNIX I/O system calls to provide the associated naming and connection semantics. Rather than overloading the existing interface, the developers used the existing interfaces to the extent that the latter worked without being changed, and designed new interfaces to handle the added semantics. The read and write system calls were used for byte-stream type connections, but six new system calls were added to allow sending and receiving addressed messages such as network datagrams. The system calls for writing messages include send, sendto, and sendmsg. The system calls for reading messages include recv, recvfrom, and recvmsg. In retrospect, the first two in each class are special cases of the others; recvfrom and sendto probably should have been added as library interfaces to recvmsg and sendmsg, respectively.

In addition to the traditional read and write system calls, 4.2BSD introduced the ability to do scatter/gather I/O. Scatter input uses the readv system call to allow a single read to be placed in several different buffers. Conversely, the writev system call allows several different buffers to be written in a single atomic write. Instead of passing a single buffer and length parameter, as is done with read and write, the process passes in a pointer to an array of buffers and lengths, along with a count describing the size of the array.

This facility allows buffers in different parts of a process address space to be written atomically, without the need to copy them to a single contiguous buffer. Atomic writes are necessary in the case where the underlying abstraction is record based, such as tape drives that output a tape block on each write request. It is also convenient to be able to read a single request into several different buffers (such as a record header into one place and the data into another). Although an application can simulate the ability to scatter data by reading the data into a large buffer and then copying the pieces to their intended destinations, the cost of memory-to-memory copying in such cases often would more than double the running time of the affected application.

Just as send and recv could have been implemented as library interfaces to sendto and recvfrom, it also would have been possible to simulate read with readv and write with writev. However, read and write are used so much more frequently that the added cost of simulating them would not have been worthwhile.

With the expansion of network computing, it became desirable to support both local and remote filesystems. To simplify the support of multiple filesystems, the developers added a new virtual node or vnode interface to the kernel. The set of operations exported from the vnode interface appear much like the filesystem operations previously supported by the local filesystem. However, they may be supported by a wide range of filesystem types:

Local disk-based filesystems

Files imported using a variety of remote filesystem protocols

Read-only CD-ROM filesystems

Filesystems providing special-purpose interfaces -- for example, the

/procfilesystem

A few variants of 4.4BSD, such as FreeBSD, allow filesystems to be loaded dynamically when the filesystems are first referenced by the mount system call. The vnode interface is described in Section 6.5; its ancillary support routines are described in Section 6.6; several of the special-purpose filesystems are described in Section 6.7.

A regular file is a linear array of bytes, and can be read and written starting at any byte in the file. The kernel distinguishes no record boundaries in regular files, although many programs recognize line-feed characters as distinguishing the ends of lines, and other programs may impose other structure. No system-related information about a file is kept in the file itself, but the filesystem stores a small amount of ownership, protection, and usage information with each file.

A filename component is a string of up to 255 characters. These filenames are stored in a type of file called a directory. The information in a directory about a file is called a directory entry and includes, in addition to the filename, a pointer to the file itself. Directory entries may refer to other directories, as well as to plain files. A hierarchy of directories and files is thus formed, and is called a filesystem;

a small one is shown in Figure 2.2, “A small filesystem”. Directories may contain subdirectories, and there is no inherent limitation to the depth with which directory nesting may occur. To protect the consistency of the filesystem, the kernel does not permit processes to write directly into directories. A filesystem may include not only plain files and directories, but also references to other objects, such as devices and sockets.

The filesystem forms a tree, the beginning of which is the

root directory,

sometimes referred to by the name

slash,

spelled with a single solidus character (/).

The root directory contains files; in our example in Fig 2.2, it contains

vmunix,

a copy of the kernel-executable object file.

It also contains directories; in this example, it contains the

usr

directory.

Within the

usr

directory is the

bin

directory, which mostly contains executable object code of programs,

such as the files

ls

and

vi.

A process identifies a file by specifying that file's pathname, which is a string composed of zero or more filenames separated by slash (/) characters. The kernel associates two directories with each process for use in interpreting pathnames. A process's root directory is the topmost point in the filesystem that the process can access; it is ordinarily set to the root directory of the entire filesystem. A pathname beginning with a slash is called an absolute pathname, and is interpreted by the kernel starting with the process's root directory.

A pathname that does not begin with a slash is called a

relative pathname,

and is interpreted relative to the

current working directory

of the process.

(This directory also is known by the shorter names

current directory

or

working directory.)

The current directory itself may be referred to directly by the name

dot,

spelled with a single period

(.).

The filename

dot-dot

(..)

refers to a directory's parent directory.

The root directory is its own parent.

A process may set its root directory with the chroot system call, and its current directory with the chdir system call. Any process may do chdir at any time, but chroot is permitted only a process with superuser privileges. Chroot is normally used to set up restricted access to the system.

Using the filesystem shown in Fig. 2.2,

if a process has the root of the filesystem as its root directory, and has

/usr

as its current directory, it can refer to the file

vi

either from the root with the absolute pathname

/usr/bin/vi,

or from its current directory with the relative pathname

bin/vi.

System utilities and databases are kept in certain well-known directories.

Part of the well-defined hierarchy includes a directory that contains the

home directory

for each user -- for example,

/usr/staff/mckusick

and

/usr/staff/karels

in Fig. 2.2.

When users log in,

the current working directory of their shell is set to the

home directory.

Within their home directories,

users can create directories as easily as they can regular files.

Thus, a user can build arbitrarily complex subhierarchies.

The user usually knows of only one filesystem, but the system may know that this one virtual filesystem is really composed of several physical filesystems, each on a different device. A physical filesystem may not span multiple hardware devices. Since most physical disk devices are divided into several logical devices, there may be more than one filesystem per physical device, but there will be no more than one per logical device. One filesystem -- the filesystem that anchors all absolute pathnames -- is called the root filesystem, and is always available. Others may be mounted; that is, they may be integrated into the directory hierarchy of the root filesystem. References to a directory that has a filesystem mounted on it are converted transparently by the kernel into references to the root directory of the mounted filesystem.

The link system call takes the name of an existing file and another name to create for that file. After a successful link, the file can be accessed by either filename. A filename can be removed with the unlink system call. When the final name for a file is removed (and the final process that has the file open closes it), the file is deleted.

Files are organized hierarchically in directories. A directory is a type of file, but, in contrast to regular files, a directory has a structure imposed on it by the system. A process can read a directory as it would an ordinary file, but only the kernel is permitted to modify a directory. Directories are created by the mkdir system call and are removed by the rmdir system call. Before 4.2BSD, the mkdir and rmdir system calls were implemented by a series of link and unlink system calls being done. There were three reasons for adding systems calls explicitly to create and delete directories:

The operation could be made atomic. If the system crashed, the directory would not be left half-constructed, as could happen when a series of link operations were used.

When a networked filesystem is being run, the creation and deletion of files and directories need to be specified atomically so that they can be serialized.

When supporting non-UNIX filesystems, such as an MS-DOS filesystem, on another partition of the disk, the other filesystem may not support link operations. Although other filesystems might support the concept of directories, they probably would not create and delete the directories with links, as the UNIX filesystem does. Consequently, they could create and delete directories only if explicit directory create and delete requests were presented.

The chown system call sets the owner and group of a file, and chmod changes protection attributes. Stat applied to a filename can be used to read back such properties of a file. The fchown, fchmod, and fstat system calls are applied to a descriptor, instead of to a filename, to do the same set of operations. The rename system call can be used to give a file a new name in the filesystem, replacing one of the file's old names. Like the directory-creation and directory-deletion operations, the rename system call was added to 4.2BSD to provide atomicity to name changes in the local filesystem. Later, it proved useful explicitly to export renaming operations to foreign filesystems and over the network.

The truncate system call was added to 4.2BSD to allow files to be shortened to an arbitrary offset. The call was added primarily in support of the Fortran run-time library, which has the semantics such that the end of a random-access file is set to be wherever the program most recently accessed that file. Without the truncate system call, the only way to shorten a file was to copy the part that was desired to a new file, to delete the old file, then to rename the copy to the original name. As well as this algorithm being slow, the library could potentially fail on a full filesystem.

Once the filesystem had the ability to shorten files, the kernel took advantage of that ability to shorten large empty directories. The advantage of shortening empty directories is that it reduces the time spent in the kernel searching them when names are being created or deleted.

Newly created files are assigned the user identifier of the process that created them and the group identifier of the directory in which they were created. A three-level access-control mechanism is provided for the protection of files. These three levels specify the accessibility of a file to

The user who owns the file

The group that owns the file

Everyone else

Each level of access has separate indicators for read permission, write permission, and execute permission.

Files are created with zero length, and may grow when they are written. While a file is open, the system maintains a pointer into the file indicating the current location in the file associated with the descriptor. This pointer can be moved about in the file in a random-access fashion. Processes sharing a file descriptor through a fork or dup system call share the current location pointer. Descriptors created by separate open system calls have separate current location pointers. Files may have holes in them. Holes are void areas in the linear extent of the file where data have never been written. A process can create these holes by positioning the pointer past the current end-of-file and writing. When read, holes are treated by the system as zero-valued bytes.

Earlier UNIX systems had a limit of 14 characters per filename component.

This limitation was often a problem.

For example,

in addition to the natural desire of users

to give files long descriptive names,

a common way of forming filenames is as

basename.extension.c

for C source or

.o

for intermediate binary object)

is one to three characters,

leaving 10 to 12 characters for the basename.

Source-code-control systems and editors usually take up another

two characters, either as a prefix or a suffix, for their purposes,

leaving eight to 10 characters.

It is easy to use 10 or 12 characters in a single

English word as a basename (e.g., ``multiplexer'').

It is possible to keep within these limits,

but it is inconvenient or even dangerous, because other UNIX

systems accept strings longer than the limit when creating files,

but then

truncate

to the limit.

A C language source file named

multiplexer.c

(already 13 characters) might have a source-code-control file

with

s.

prepended, producing a filename

s.multiplexer

that is indistinguishable from the source-code-control file for

multiplexer.ms,

a file containing

troff

source for documentation for the C program.

The contents of the two original files could easily get confused

with no warning from the source-code-control system.

Careful coding can detect this problem, but the

long filenames

first introduced in 4.2BSD practically eliminate it.

The operations defined for local filesystems are divided into two parts. Common to all local filesystems are hierarchical naming, locking, quotas, attribute management, and protection. These features are independent of how the data will be stored. 4.4BSD has a single implementation to provide these semantics.

The other part of the local filesystem is the organization and management of the data on the storage media. Laying out the contents of files on the storage media is the responsibility of the filestore. 4.4BSD supports three different filestore layouts:

The traditional Berkeley Fast Filesystem

The log-structured filesystem, based on the Sprite operating-system design [Rosenblum & Ousterhout, 1992]

A memory-based filesystem

Although the organizations of these filestores are completely different, these differences are indistinguishable to the processes using the filestores.

The Fast Filesystem organizes data into cylinder groups. Files that are likely to be accessed together, based on their locations in the filesystem hierarchy, are stored in the same cylinder group. Files that are not expected to accessed together are moved into different cylinder groups. Thus, files written at the same time may be placed far apart on the disk.

The log-structured filesystem organizes data as a log. All data being written at any point in time are gathered together, and are written at the same disk location. Data are never overwritten; instead, a new copy of the file is written that replaces the old one. The old files are reclaimed by a garbage-collection process that runs when the filesystem becomes full and additional free space is needed.

The memory-based filesystem is designed to store data in virtual memory.

It is used for filesystems that need to support

fast but temporary data, such as

/tmp.

The goal of the memory-based filesystem is to keep

the storage packed as compactly as possible to minimize

the usage of virtual-memory resources.

Initially, networking was used to transfer data from one machine to another. Later, it evolved to allowing users to log in remotely to another machine. The next logical step was to bring the data to the user, instead of having the user go to the data -- and network filesystems were born. Users working locally do not experience the network delays on each keystroke, so they have a more responsive environment.

Bringing the filesystem to a local machine was among the first of the major client-server applications. The server is the remote machine that exports one or more of its filesystems. The client is the local machine that imports those filesystems. From the local client's point of view, a remotely mounted filesystem appears in the file-tree name space just like any other locally mounted filesystem. Local clients can change into directories on the remote filesystem, and can read, write, and execute binaries within that remote filesystem identically to the way that they can do these operations on a local filesystem.

When the local client does an operation on a remote filesystem, the request is packaged and is sent to the server. The server does the requested operation and returns either the requested information or an error indicating why the request was denied. To get reasonable performance, the client must cache frequently accessed data. The complexity of remote filesystems lies in maintaining cache consistency between the server and its many clients.

Although many remote-filesystem protocols have been developed over the years, the most pervasive one in use among UNIX systems is the Network Filesystem (NFS), whose protocol and most widely used implementation were done by Sun Microsystems. The 4.4BSD kernel supports the NFS protocol, although the implementation was done independently from the protocol specification [Macklem, 1994]. The NFS protocol is described in Chapter 9.

Terminals support the standard system I/O operations, as well as a collection of terminal-specific operations to control input-character editing and output delays. At the lowest level are the terminal device drivers that control the hardware terminal ports. Terminal input is handled according to the underlying communication characteristics, such as baud rate, and according to a set of software-controllable parameters, such as parity checking.

Layered above the terminal device drivers are line disciplines that provide various degrees of character processing. The default line discipline is selected when a port is being used for an interactive login. The line discipline is run in canonical mode; input is processed to provide standard line-oriented editing functions, and input is presented to a process on a line-by-line basis.

Screen editors and programs that communicate with other computers generally run in noncanonical mode (also commonly referred to as raw mode or character-at-a-time mode). In this mode, input is passed through to the reading process immediately and without interpretation. All special-character input processing is disabled, no erase or other line editing processing is done, and all characters are passed to the program that is reading from the terminal.

It is possible to configure the terminal in thousands of combinations between these two extremes. For example, a screen editor that wanted to receive user interrupts asynchronously might enable the special characters that generate signals and enable output flow control, but otherwise run in noncanonical mode; all other characters would be passed through to the process uninterpreted.

On output, the terminal handler provides simple formatting services, including

Converting the line-feed character to the two-character carriage-return-line-feed sequence

Inserting delays after certain standard control characters

Expanding tabs

Displaying echoed nongraphic ASCII characters as a two-character sequence of the form ``^C'' (i.e., the ASCII caret character followed by the ASCII character that is the character's value offset from the ASCII ``@'' character).

Each of these formatting services can be disabled individually by a process through control requests.

Interprocess communication in 4.4BSD is organized in communication domains. Domains currently supported include the local domain, for communication between processes executing on the same machine; the internet domain, for communication between processes using the TCP/IP protocol suite (perhaps within the Internet); the ISO/OSI protocol family for communication between sites required to run them; and the XNS domain, for communication between processes using the XEROX Network Systems (XNS) protocols.

Within a domain, communication takes place between communication endpoints known as sockets. As mentioned in Section 2.6, the socket system call creates a socket and returns a descriptor; other IPC system calls are described in Chapter 11. Each socket has a type that defines its communications semantics; these semantics include properties such as reliability, ordering, and prevention of duplication of messages.

Each socket has associated with it a communication protocol. This protocol provides the semantics required by the socket according to the latter's type. Applications may request a specific protocol when creating a socket, or may allow the system to select a protocol that is appropriate for the type of socket being created.

Sockets may have addresses bound to them. The form and meaning of socket addresses are dependent on the communication domain in which the socket is created. Binding a name to a socket in the local domain causes a file to be created in the filesystem.

Normal data transmitted and received through sockets are untyped. Data-representation issues are the responsibility of libraries built on top of the interprocess-communication facilities. In addition to transporting normal data, communication domains may support the transmission and reception of specially typed data, termed access rights. The local domain, for example, uses this facility to pass descriptors between processes.

Networking implementations on UNIX before 4.2BSD usually worked by overloading the character-device interfaces. One goal of the socket interface was for naive programs to be able to work without change on stream-style connections. Such programs can work only if the read and write systems calls are unchanged. Consequently, the original interfaces were left intact, and were made to work on stream-type sockets. A new interface was added for more complicated sockets, such as those used to send datagrams, with which a destination address must be presented with each send call.

Another benefit is that the new interface is highly portable. Shortly after a test release was available from Berkeley, the socket interface had been ported to System III by a UNIX vendor (although AT&T did not support the socket interface until the release of System V Release 4, deciding instead to use the Eighth Edition stream mechanism). The socket interface was also ported to run in many Ethernet boards by vendors, such as Excelan and Interlan, that were selling into the PC market, where the machines were too small to run networking in the main processor. More recently, the socket interface was used as the basis for Microsoft's Winsock networking interface for Windows.

Some of the communication domains supported by the socket IPC mechanism provide access to network protocols. These protocols are implemented as a separate software layer logically below the socket software in the kernel. The kernel provides many ancillary services, such as buffer management, message routing, standardized interfaces to the protocols, and interfaces to the network interface drivers for the use of the various network protocols.

At the time that 4.2BSD was being implemented, there were many networking protocols in use or under development, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. There was no clearly superior protocol or protocol suite. By supporting multiple protocols, 4.2BSD could provide interoperability and resource sharing among the diverse set of machines that was available in the Berkeley environment. Multiple-protocol support also provides for future changes. Today's protocols designed for 10- to 100-Mbit-per-second Ethernets are likely to be inadequate for tomorrow's 1- to 10-Gbit-per-second fiber-optic networks. Consequently, the network-communication layer is designed to support multiple protocols. New protocols are added to the kernel without the support for older protocols being affected. Older applications can continue to operate using the old protocol over the same physical network as is used by newer applications running with a newer network protocol.

The first protocol suite implemented in 4.2BSD was DARPA's Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP). The CSRG chose TCP/IP as the first network to incorporate into the socket IPC framework, because a 4.1BSD-based implementation was publicly available from a DARPA-sponsored project at Bolt, Beranek, and Newman (BBN). That was an influential choice: The 4.2BSD implementation is the main reason for the extremely widespread use of this protocol suite. Later performance and capability improvements to the TCP/IP implementation have also been widely adopted. The TCP/IP implementation is described in detail in Chapter 13.

The release of 4.3BSD added the Xerox Network Systems (XNS) protocol suite, partly building on work done at the University of Maryland and at Cornell University. This suite was needed to connect isolated machines that could not communicate using TCP/IP.

The release of 4.4BSD added the ISO protocol suite because of the latter's increasing visibility both within and outside the United States. Because of the somewhat different semantics defined for the ISO protocols, some minor changes were required in the socket interface to accommodate these semantics. The changes were made such that they were invisible to clients of other existing protocols. The ISO protocols also required extensive addition to the two-level routing tables provided by the kernel in 4.3BSD. The greatly expanded routing capabilities of 4.4BSD include arbitrary levels of routing with variable-length addresses and network masks.

Bootstrapping mechanisms are used to start the system running. First, the 4.4BSD kernel must be loaded into the main memory of the processor. Once loaded, it must go through an initialization phase to set the hardware into a known state. Next, the kernel must do autoconfiguration, a process that finds and configures the peripherals that are attached to the processor. The system begins running in single-user mode while a start-up script does disk checks and starts the accounting and quota checking. Finally, the start-up script starts the general system services and brings up the system to full multiuser operation.

During multiuser operation, processes wait for login requests on the terminal lines and network ports that have been configured for user access. When a login request is detected, a login process is spawned and user validation is done. When the login validation is successful, a login shell is created from which the user can run additional processes.

[Accetta et al, 1986] “Mach: A New Kernel Foundation for UNIX Development"”. 93-113. USENIX Association Conference Proceedings. USENIX Association. June 1986.

[Ewens et al, 1985] “Tunis: A Distributed Multiprocessor Operating System”. 247-254. USENIX Assocation Conference Proceedings. USENIX Association. June 1985.

[Gingell et al, 1987] “Virtual Memory Architecture in SunOS”. 81-94. USENIX Association Conference Proceedings. USENIX Association. June 1987.

[Kernighan & Pike, 1984] The UNIX Programming Environment. Prentice-Hall. Englewood Cliffs NJ . 1984.

[Macklem, 1994] The 4.4BSD NFS Implementation. 6:1-14. 4.4BSD System Manager's Manual. O'Reilly & Associates, Inc.. Sebastopol CA . 1994.

[McKusick & Karels, 1988] “Design of a General Purpose Memory Allocator for the 4.3BSD UNIX Kernel”. 295-304. USENIX Assocation Conference Proceedings. USENIX Assocation. June 1998.

[McKusick et al, 1994] Berkeley Software Architecture Manual, 4.4BSD Edition. 5:1-42. 4.4BSD Programmer's Supplementary Documents. O'Reilly & Associates, Inc.. Sebastopol CA . 1994.

[Rosenblum & Ousterhout, 1992] “The Design and Implementation of a Log-Structured File System”. 26-52. ACM Transactions on Computer Systems, 10, 1. Association for Computing Machinery. February 1992.