We have presented many examples of client/server applications in this book, all of which assume that the client and server programs are running either on the same host, or on multiple hosts with no network restrictions. We can justify this assumption because this is an instructional text, but a real-world network environment is usually much more complicated: client and server hosts with access to public networks often reside behind protective router-firewalls that not only restrict incoming connections, but also allow the protected networks to run in a private address space using Network Address Translation (NAT). These features, which are practically mandatory in today’s hostile network environments, also disrupt the ideal world in which our examples are running.

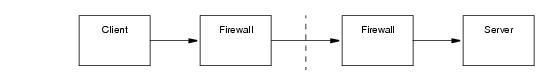

Let us assume that a client and server need to communicate over an untrusted network, and that the client and server hosts reside in private networks behind firewalls, as shown in

Figure 42.1.

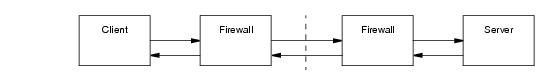

To complicate the scenario even further, Figure 42.2 adds a callback from the server to the client. Callbacks imply that the client is also a server, therefore all of the issues associated with

Figure 42.1 now apply to the client as well.

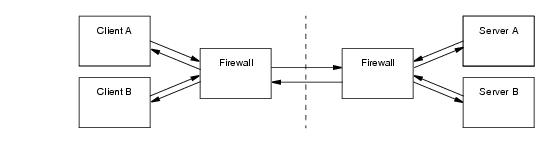

As if this was not complicated enough already, Figure 42.3 adds multiple clients and servers. Each additional server (including clients requiring callbacks) adds more work for the firewall administrator as more ports are dedicated to forwarding requests.

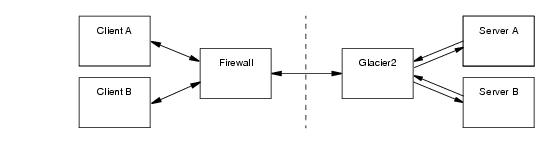

Glacier2, the router-firewall for Ice applications, addresses the issues raised in Section 42.2.1 with minimal impact on clients or servers (or firewall administrators). In

Figure 42.4, Glacier2 becomes the server firewall for Ice applications. What is not obvious in the diagram, however, is how Glacier2 eliminates much of the complexity of the previous scenarios.

The Ice core supports a generic router facility, represented by the Ice::Router interface, that allows a third-party service to “intercept” requests on a properly-configured proxy and deliver them to the intended server. Glacier2 is an implementation of this service, although other implementations are certainly possible.

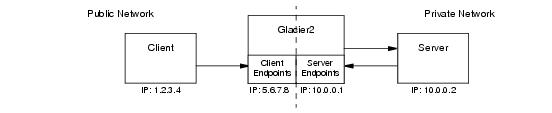

Glacier2 normally runs on a host in the private network behind a port-forwarding firewall (see

Section 42.11), but it can also operate on a host with access to both public and private networks. In this configuration it follows that Glacier2 must have endpoints on each network, as shown in

Figure 42.5.

In the client, proxies must be configured to use Glacier2 as a router. This configuration can be done statically for all proxies created by a communicator, or programmatically for a particular proxy. A proxy configured to use a router is called a

routed proxy.

When a client invokes an operation on a routed proxy, the client connects to one of Glacier2’s client endpoints and sends the request as if Glacier2 were the server. Glacier2 then establishes a client connection to the intended server, forwards the request, and returns the reply (if any). Glacier2 is essentially acting as a local client on behalf of the remote client.

If a server returns a proxy as the result of an operation, that proxy contains the server’s endpoints in the private network, as usual. (Remember, the server is unaware of Glacier2’s presence, and therefore assumes that the proxy is usable by the client that requested it.) Of course, those endpoints are not accessible to the client and, in the absence of a router, the client would receive an exception if it were to use the proxy. When that proxy is configured with a router, however, the client ignores the server’s endpoints and only sends requests to the router’s client endpoints.