This tutorial covers how to write components that provide a "selected object" and how to write components that update themselves as the global selection changes.

"Selection" is an important concept for any non-trivial

application. NetBeans has two basic concepts of selection—the contents of

the focused

TopComponent's

Lookup, and

the focused TopComponent's

activated Node(s). Here you will deal only with the Lookup

portion of selection—doing more advanced things will be covered in a later

tutorial.

Selection is used to make possible such things as context sensitive actions (actions that are enabled or disabled depending on what is displayed), and palette windows such as the Property Sheet or Navigator components in the IDE, which each display some aspect of whatever is selected.

Basically, each TopComponent has a bag of objects that it can put things

into, and which other code is able to query. That bag of objects is its

Lookup—essentially a Map where the keys are class objects and the

values are objects that extend or implement the key-class. The thing that

makes this approach tremendously useful is the ability to use this mechanism

to decouple the components that provide some object and the components that

consume those objects—so they can be implemented in separate modules, or

new editors for old objects can be provided and the rest of the system will

continue to work transparently.

To download the completed sample, click here.

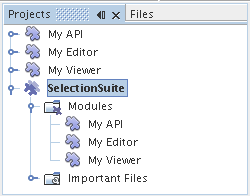

The example for this tutorial will contain three modules, contained within a module suite, as illustrated below:

Start by creating the module suite to contain all three modules:

Right click the org.myorg.myapi package and choose

New > Java Class, as shown below:

APIObject.

public final class APIObject {

private final Date date = new Date();

private static int count = 0;

private final int index;

public APIObject() {

index = count++;

}

public Date getDate() {

return date;

}

public int getIndex() {

return index;

}

public String toString() {

return index + " - " + date;

}

}

This will be all of the code that this module contains. As you can see,

each time a new instance of APIObject is created, a counter

is incremented—so there will be some unique attribute to each instance

of APIObject.

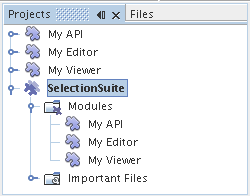

org.myorg.myapi

package so other modules can see classes in it. Right click the My API project

and choose Properties.In the API Versioning page

in the Project Properties dialog box, check the

checkbox for org.myorg.api in the

Public Packages list, shown below:

APIObject class, so each of them needs to

say that they depend on the API module.

For each of the other module projects in turn,

right click the project node and choose Properties.

In the Libraries page of each Project

Properties dialog box, click the Add Dependency

button. In the dialog box that pops up,

type APIObject—there

should be only one match, which is your API module.

Select it and click

OK to add the dependency.

Now you will create a singleton component that will track if there is an

APIObject available in the global selection (i.e., if the

focused TopComponent has one in its Lookup). If there is one, it will display

some data about it. One common use case for this sort of thing is creating

master/detail views.

A "singleton component" is a component like the Projects window in the NetBeans IDE, or the Property Sheet or the Navigator—a component that there is only ever one of in the system. The Window Component wizard will automatically generate all of the code needed to create such a singleton component—you just have to use the form designer or write code to provide the contents of your singleton component.

org.myorg.myviewer package and choose

New > Other.On the "Basic Settings" page of the wizard,

select navigator as the

location in which to place your viewer component, and check the

checkbox to open the component on startup,

as shown below:

MyViewer and

click Finish (or press Enter).TopComponent—a singleton component called

MyViewerTopComponent. Click the editor tab for

MyViewerTopComponent—the form editor should be visible.

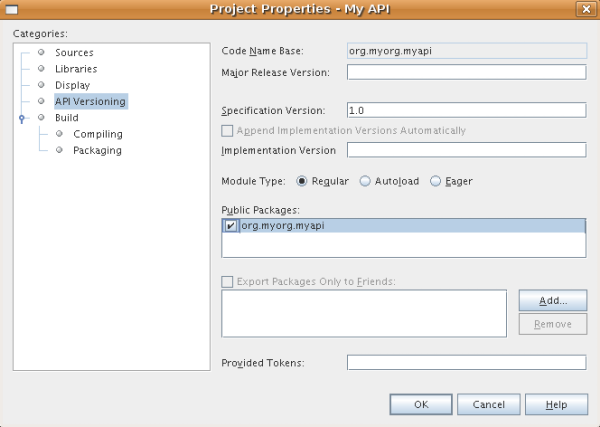

You will add two labels to the component, which will display some information

about the selected APIObject if there is one.

Drag two JLabels to the form from the Palette, one below the other.

Change the text of the first as shown above, so that by default it displays "[nothing selected]".

MyViewerTopComponent

implements LookupListener:

public class MyViewerTopComponent extends TopComponent implements LookupListener {

LookupListener is imported.Put the caret in the signature line as shown below. A lightbulb glyph should appear in the editor margin. Press Alt-Enter, and then Enter again when the popup appears with the text "Implement All Abstract Methods". This will add the LookupListener method to your class.

LookupListener. Now it needs

something to listen to. In your case, there is a convenient global Lookup

object, which simply proxies the Lookup of whatever component has focus—it

can be obtained from the call Utilities.actionsGlobalContext().

So rather than tracking what component has focus yourself, you can simply

listen to this one global selection lookup, which will fire appropriate

changes whenever focus changes. Edit the source code so that it contains

the following methods as shown here:

private Lookup.Result result = null;

public void componentOpened() {

Lookup.Template tpl = new Lookup.Template (APIObject.class);

result = Utilities.actionsGlobalContext().lookup(tpl);

result.addLookupListener (this);

}

public void componentClosed() {

result.removeLookupListener (this);

result = null;

}

public void resultChanged(LookupEvent lookupEvent) {

Lookup.Result r = (Lookup.Result) lookupEvent.getSource();

Collection c = r.allInstances();

if (!c.isEmpty()) {

APIObject o = (APIObject) c.iterator().next();

jLabel1.setText (Integer.toString(o.getIndex()));

jLabel2.setText (o.getDate().toString());

} else {

jLabel1.setText("[no selection]");

jLabel2.setText ("");

}

}

componentOpened() is called whenever the component is

made visible by the window system; componentClosed() is

called whenever the user clicks the X button on its tab to close it.

So whenever the component is showing, you want it to be tracking the

selection—which is what the above code does.

The resultChanged() method is your implementation of

LookupListener. Whenever the selected APIObject

changes, it will update the two JLabels you put on the form.

Now you need something to actually provide instances of APIObject,

for this code to be of any use. Fortunately this is quite simple.

You will create another TopComponent, this time, one that opens

in the editor area and offers an instance of APIObject from

its Lookup. You could use the Window Component template

again, but that template is designed for creating singleton components, rather

than components there can be many of. So you will simply create a TopComponent

subclass without the template, and an action which will open additional ones.

TopComponent. The

dialog should automatically suggest setting a dependency on the

Window System API. Do the same thing for Lookups (Utilities

API).org.myorg.myeditor package in the

My Editor project, and choose New > JPanel Form.false for each one.MyEditor to extends TopComponent

instead of javax.swing.JPanel:

public class MyEditor extends TopComponent {

MyEditor:

APIObject obj = new APIObject();

associateLookup (Lookups.singleton (obj);

jTextField1.setText ("APIObject #" + obj.getIndex());

jTextField2.setText ("Created: " + obj.getDate());

setDisplayName ("MyEditor " + obj.getIndex());

Right-click in the editor

and choose Fix Imports.

The line

associateLookup (Lookups.singleton (obj));

will create a Lookup that contains only one object—the new

instance of APIObject—and assign that Lookup

to be what is returned by MyEditor.getLookup().

While this is an artificial example,

you can imagine how APIObject might represent a file, an entity in a

database or anything else you might want to edit or view. Probably you

can also imagine one component that allowed you to select or edit multiple

unique instances of APIObject—that will be the subject of the

next tutorial.

To make your editor component at least somewhat interesting (though it

doesn't actually edit anything), you set the text

fields' values to values from the APIObject, so you have

something to display.

MyEditor components in the editor

area, so that there will be something to show. To do anything meaningful

with selection, you will need more than one editor so that there is more

than one APIObject to track.

Since you will want multiple editors,

you need a simple action on the main menu which will create and open another instance

of MyEditor in the window system (as opposed to what the

Window Component template would create for us, which is an action that always

looks up a singleton component such as the Navigator or Property Sheet components

in the IDE).

org.myorg.myeditor package and choose

New > Other.OpenEditorAction and set its display name to say

"Open Editor".OpenEditorAction,

which subclasses CallableSystemAction (a NetBeans subclass of

javax.swing.Action which lets you associate context sensitive

help with an action). Add the following code to its performAction()

method:

MyEditor editor = new MyEditor(); editor.open(); editor.requestActive();The above code will simply create a new instance of

MyEditor (which

in turn will create a new instance of APIObject and put it in

its Lookup) and

open it in the window system.

Now you're ready to run the tutorial. Simply right click SelectionSuite,

the module suite which owns your three modules, and choose Run from the popup

menu. When the IDE opens, simply choose File > Open Editor—invoke your

action. Do this a couple of times, so that there are several of your editor

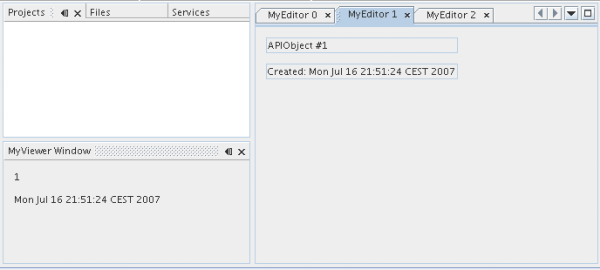

components open. Your singleton MyViewer window should also be open. Notice how

the MyViewer window's contents change as you click different tabs,

as shown here:

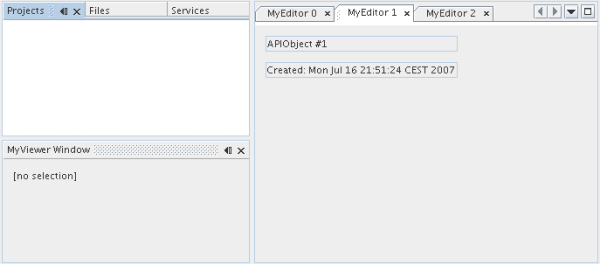

If you click in the Projects window, notice that the text changes to "[No Selection]", as shown below:

If you do not see the MyViewer window, you probably did not check

the checkbox in the wizard to open it on system start—simply go to the

Window menu and choose Open MyViewer Window to display it.

APIObject from its Lookup.

To really picture the value of this, imagine APIObject were something

much more complex; imagine that MyEditor is an image editor, and

APIObject represents an image being edited. The thing that's powerful here is

that you could replace MyEditor with, say, an SVG vector-based editor,

and the viewer component (presumably showing attributes of the currently edited image)

will work transparently with that new editor. It is this model of doing things

that is the reason you can add new tools into the NetBeans IDE that work against Java

files, and they will work in different versions of NetBeans, and that you can have

an alternate editor (such as the form editor) for Java files and all the components

and actions that work against Java files still work when the form editor is used.

This is very much the way NetBeans works with Java and other source files—

in their case, the thing that is available from the editor's Lookup is a

DataObject,

and components like Navigator and the Property Sheet are simply watching what object is

being made available by the focused TopComponent.

Another valuable thing about this approach is that often people are migrating existing applications to the NetBeans platform. The object that is part of the data model, in that case, is probably existing, working code that should not be changed in order to integrate it into NetBeans. By keeping the data model's API in a separate module, the NetBeans integration can be kept separate from the core business logic.

APIObject

it has with a new one on the fly.

MyEditor in the form editor (click the Design toolbar

button in the editor toolbar), and drag a JButton to it.text property of the JButton to "Replace".JButton and choose Events > Action > actionPerformed.

This will cause the code editor to open with the caret in an event handler method.

public class MyEditor extends TopComponent {

private final InstanceContent content = new InstanceContent();

InstanceContent is a class which allows us to modify the content of a Lookup

(specifically an instance of AbstractLookup) on the fly.

associateLookup (new AbstractLookup (content));

jButton1ActionPerformed (null);

private void jButton1ActionPerformed(java.awt.event.ActionEvent evt) {

APIObject obj = new APIObject();

jTextField1.setText ("APIObject #" + obj.getIndex());

jTextField2.setText ("Created: " + obj.getDate());

setDisplayName ("MyEditor " + obj.getIndex());

content.set(Collections.singleton (obj), null);

}

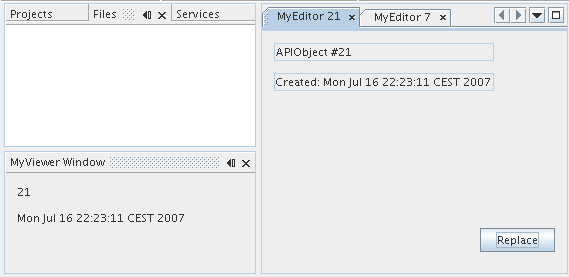

You're now ready to run the suite again. Right click SelectionSuite again and

choose Run. Notice how, now, when you click the Replace button, all of the

components update, including the instance of MyViewer—everything.

Map that only contains

one key and one value? The answer is, yes, it is like that. Where this technique becomes

even more powerful is when you provide multiple objects from multiple APIs.

As an example, it is very common in NetBeans to provide context sensitive

actions. A case in point is the built-in SaveAction that is part

of NetBeans' Actions API. What this action actually does is, it simply listens

for the presence of something called SaveCookie on the global context—

the same way your viewer window listens for APIObject. If a SaveCookie

appears (editors typically add one to their lookup when the content of the file

is modified but not yet saved), the action becomes enabled, so the Save toolbar

button and menu items become enabled. When the Save action is invoked, it calls

SaveCookie.save(), which in turn causes the SaveCookie to

disappear, so the Save action then becomes disabled until a new one appears.

As you may have noticed, context sensitivity was one option in the New

Action wizard. The actions currently generated by the wizard actually

use a way of doing this that pre-dates Lookup; the Lookup-based way of doing such

context sensitive actions is described

in the developer FAQ.

So the pattern in practice is to provide more than just a single object from

your component's Lookup—different auxilliary components and different

actions will be interested in different aspects of the object being edited. These

aspects can be cleanly separated into interfaces which those auxilliary components

and actions can depend on and listen for.

While not directly related to the topic of this tutorial, it's worth noticing

that if you open three MyEditor instances, and shut down and restart

NetBeans, you end up with three MyEditor instances magically appearing

on restart. By default, your editors are serialized to disk on shutdown and

restored on restart.

If you do not want this behavior, there are two other choices. Override

the following method on MyEditor to cause editors never to be reopened on restart:

public int getPersistenceType() {

return PERSISTENCE_NEVER;

}

If you want to persist the components that are open but discard those that have

been closed, return PERSISTENCE_ONLY_OPENED instead. The default

(for backward compatibility reasons) is PERSISTENCE_ALWAYS, which

is not appropriate for editor-style componenents—it means that even editors that have been closed

are kept forever and reloaded on restart.

Note, though, that part of what is serialized to disk is the location of

your component in the main window. So singleton TopComponentss such as the

property sheet, or our viewer component, should use PERSISTENCE_ALWAYS -

otherwise if they are closed once by the user, the next time they are opened they

will appear in the editor area instead of where they are supposed to be.

layer.xml file to install objects. In the case of the

My API module, it is actually not used. So a polite thing to do to get a

slight improvement in startup time would be the following:

OpenIDE-Module-Layer: org/myorg/myapi/layer.xml

layer.xml file in

org.myorg.myapi