Chapter 2. Securing Your Network

2.1. Workstation Security

Securing a Linux environment begins with the workstation. Whether locking down a personal machine or securing an enterprise system, sound security policy begins with the individual computer. A computer network is only as secure as its weakest node.

2.1.1. Evaluating Workstation Security

When evaluating the security of a Red Hat Enterprise Linux workstation, consider the following:

BIOS and Boot Loader Security — Can an unauthorized user physically access the machine and boot into single user or rescue mode without a password?

Password Security — How secure are the user account passwords on the machine?

Administrative Controls — Who has an account on the system and how much administrative control do they have?

Available Network Services — What services are listening for requests from the network and should they be running at all?

Personal Firewalls — What type of firewall, if any, is necessary?

Security Enhanced Communication Tools — Which tools should be used to communicate between workstations and which should be avoided?

2.1.2. BIOS and Boot Loader Security

Password protection for the BIOS (or BIOS equivalent) and the boot loader can prevent unauthorized users who have physical access to systems from booting using removable media or obtaining root privileges through single user mode. The security measures you should take to protect against such attacks depends both on the sensitivity of the information on the workstation and the location of the machine.

For example, if a machine is used in a trade show and contains no sensitive information, then it may not be critical to prevent such attacks. However, if an employee's laptop with private, unencrypted SSH keys for the corporate network is left unattended at that same trade show, it could lead to a major security breach with ramifications for the entire company.

If the workstation is located in a place where only authorized or trusted people have access, however, then securing the BIOS or the boot loader may not be necessary.

The two primary reasons for password protecting the BIOS of a computer are[]:

Preventing Changes to BIOS Settings — If an intruder has access to the BIOS, they can set it to boot from a diskette or CD-ROM. This makes it possible for them to enter rescue mode or single user mode, which in turn allows them to start arbitrary processes on the system or copy sensitive data.

Preventing System Booting — Some BIOSes allow password protection of the boot process. When activated, an attacker is forced to enter a password before the BIOS launches the boot loader.

Because the methods for setting a BIOS password vary between computer manufacturers, consult the computer's manual for specific instructions.

If you forget the BIOS password, it can either be reset with jumpers on the motherboard or by disconnecting the CMOS battery. For this reason, it is good practice to lock the computer case if possible. However, consult the manual for the computer or motherboard before attempting to disconnect the CMOS battery.

2.1.2.2. Boot Loader Passwords

The primary reasons for password protecting a Linux boot loader are as follows:

Preventing Access to Single User Mode — If attackers can boot the system into single user mode, they are logged in automatically as root without being prompted for the root password.

Preventing Access to the GRUB Console — If the machine uses GRUB as its boot loader, an attacker can use the GRUB editor interface to change its configuration or to gather information using the cat command.

Preventing Access to Insecure Operating Systems — If it is a dual-boot system, an attacker can select an operating system at boot time (for example, DOS), which ignores access controls and file permissions.

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 ships with the GRUB boot loader on the x86 platform. For a detailed look at GRUB, refer to the Red Hat Installation Guide.

2.1.2.2.1. Password Protecting GRUB

You can configure GRUB to address the first two issues listed in

Section 2.1.2.2, “Boot Loader Passwords” by adding a password directive to its configuration file. To do this, first choose a strong password, open a shell, log in as root, and then type the following command:

/sbin/grub-md5-crypt

When prompted, type the GRUB password and press Enter. This returns an MD5 hash of the password.

Next, edit the GRUB configuration file /boot/grub/grub.conf. Open the file and below the timeout line in the main section of the document, add the following line:

password --md5 <password-hash>

Replace <password-hash> with the value returned by /sbin/grub-md5-crypt[].

The next time the system boots, the GRUB menu prevents access to the editor or command interface without first pressing p followed by the GRUB password.

Unfortunately, this solution does not prevent an attacker from booting into an insecure operating system in a dual-boot environment. For this, a different part of the /boot/grub/grub.conf file must be edited.

Look for the title line of the operating system that you want to secure, and add a line with the lock directive immediately beneath it.

For a DOS system, the stanza should begin similar to the following:

title DOS lock

A password line must be present in the main section of the /boot/grub/grub.conf file for this method to work properly. Otherwise, an attacker can access the GRUB editor interface and remove the lock line.

To create a different password for a particular kernel or operating system, add a lock line to the stanza, followed by a password line.

Each stanza protected with a unique password should begin with lines similar to the following example:

title DOS lock password --md5 <password-hash>

Passwords are the primary method that Red Hat Enterprise Linux uses to verify a user's identity. This is why password security is so important for protection of the user, the workstation, and the network.

For security purposes, the installation program configures the system to use Secure Hash Algorithm 512 (SHA512) and shadow passwords. It is highly recommended that you do not alter these settings.

If shadow passwords are deselected during installation, all passwords are stored as a one-way hash in the world-readable /etc/passwd file, which makes the system vulnerable to offline password cracking attacks. If an intruder can gain access to the machine as a regular user, he can copy the /etc/passwd file to his own machine and run any number of password cracking programs against it. If there is an insecure password in the file, it is only a matter of time before the password cracker discovers it.

Shadow passwords eliminate this type of attack by storing the password hashes in the file /etc/shadow, which is readable only by the root user.

This forces a potential attacker to attempt password cracking remotely by logging into a network service on the machine, such as SSH or FTP. This sort of brute-force attack is much slower and leaves an obvious trail as hundreds of failed login attempts are written to system files. Of course, if the cracker starts an attack in the middle of the night on a system with weak passwords, the cracker may have gained access before dawn and edited the log files to cover his tracks.

In addition to format and storage considerations is the issue of content. The single most important thing a user can do to protect his account against a password cracking attack is create a strong password.

2.1.3.1. Creating Strong Passwords

When creating a secure password, it is a good idea to follow these guidelines:

Do Not Use Only Words or Numbers — Never use only numbers or words in a password.

Some insecure examples include the following:

Do Not Use Recognizable Words — Words such as proper names, dictionary words, or even terms from television shows or novels should be avoided, even if they are bookended with numbers.

Some insecure examples include the following:

Do Not Use Words in Foreign Languages — Password cracking programs often check against word lists that encompass dictionaries of many languages. Relying on foreign languages for secure passwords is not secure.

Some insecure examples include the following:

cheguevara

bienvenido1

1dumbKopf

Do Not Use Hacker Terminology — If you think you are elite because you use hacker terminology — also called l337 (LEET) speak — in your password, think again. Many word lists include LEET speak.

Some insecure examples include the following:

Do Not Use Personal Information — Avoid using any personal information in your passwords. If the attacker knows your identity, the task of deducing your password becomes easier. The following is a list of the types of information to avoid when creating a password:

Some insecure examples include the following:

Do Not Invert Recognizable Words — Good password checkers always reverse common words, so inverting a bad password does not make it any more secure.

Some insecure examples include the following:

Do Not Write Down Your Password — Never store a password on paper. It is much safer to memorize it.

Do Not Use the Same Password For All Machines — It is important to make separate passwords for each machine. This way if one system is compromised, all of your machines are not immediately at risk.

The following guidelines will help you to create a strong password:

Make the Password at Least Eight Characters Long — The longer the password, the better. If using MD5 passwords, it should be 15 characters or longer. With DES passwords, use the maximum length (eight characters).

Mix Upper and Lower Case Letters — Red Hat Enterprise Linux is case sensitive, so mix cases to enhance the strength of the password.

Mix Letters and Numbers — Adding numbers to passwords, especially when added to the middle (not just at the beginning or the end), can enhance password strength.

Include Non-Alphanumeric Characters — Special characters such as &, $, and > can greatly improve the strength of a password (this is not possible if using DES passwords).

Pick a Password You Can Remember — The best password in the world does little good if you cannot remember it; use acronyms or other mnemonic devices to aid in memorizing passwords.

With all these rules, it may seem difficult to create a password that meets all of the criteria for good passwords while avoiding the traits of a bad one. Fortunately, there are some steps you can take to generate an easily-remembered, secure password.

2.1.3.1.1. Secure Password Creation Methodology

There are many methods that people use to create secure passwords. One of the more popular methods involves acronyms. For example:

Think of an easily-remembered phrase, such as:

"over the river and through the woods, to grandmother's house we go."

Next, turn it into an acronym (including the punctuation).

otrattw,tghwg.

Add complexity by substituting numbers and symbols for letters in the acronym. For example, substitute 7 for t and the at symbol (@) for a:

o7r@77w,7ghwg.

Add more complexity by capitalizing at least one letter, such as H.

o7r@77w,7gHwg.

Finally, do not use the example password above for any systems, ever.

While creating secure passwords is imperative, managing them properly is also important, especially for system administrators within larger organizations. The following section details good practices for creating and managing user passwords within an organization.

2.1.3.2. Creating User Passwords Within an Organization

If an organization has a large number of users, the system administrators have two basic options available to force the use of good passwords. They can create passwords for the user, or they can let users create their own passwords, while verifying the passwords are of acceptable quality.

Creating the passwords for the users ensures that the passwords are good, but it becomes a daunting task as the organization grows. It also increases the risk of users writing their passwords down.

For these reasons, most system administrators prefer to have the users create their own passwords, but actively verify that the passwords are good and, in some cases, force users to change their passwords periodically through password aging.

2.1.3.2.1. Forcing Strong Passwords

To protect the network from intrusion it is a good idea for system administrators to verify that the passwords used within an organization are strong ones. When users are asked to create or change passwords, they can use the command line application

passwd, which is

Pluggable Authentication Modules (

PAM) aware and therefore checks to see if the password is too short or otherwise easy to crack. This check is performed using the

pam_cracklib.so PAM module. Since PAM is customizable, it is possible to add more password integrity checkers, such as

pam_passwdqc (available from

http://www.openwall.com/passwdqc/) or to write a new module. For a list of available PAM modules, refer to

http://www.kernel.org/pub/linux/libs/pam/modules.html. For more information about PAM, refer to

Managing Single Sign-On and Smart Cards.

The password check that is performed at the time of their creation does not discover bad passwords as effectively as running a password cracking program against the passwords.

Many password cracking programs are available that run under Red Hat Enterprise Linux, although none ship with the operating system. Below is a brief list of some of the more popular password cracking programs:

John The Ripper — A fast and flexible password cracking program. It allows the use of multiple word lists and is capable of brute-force password cracking. It is available online at

http://www.openwall.com/john/.

Slurpie —

Slurpie is similar to

John The Ripper and

Crack, but it is designed to run on multiple computers simultaneously, creating a distributed password cracking attack. It can be found along with a number of other distributed attack security evaluation tools online at

http://www.ussrback.com/distributed.htm.

Always get authorization in writing before attempting to crack passwords within an organization.

Passphrases and passwords are the cornerstone to security in most of today's systems. Unfortunately, techniques such as biometrics and two-factor authentication have not yet become mainstream in many systems. If passwords are going to be used to secure a system, then the use of passphrases should be considered. Passphrases are longer than passwords and provide better protection than a password even when implemented with non-standard characters such as numbers and symbols.

2.1.3.2.3. Password Aging

Password aging is another technique used by system administrators to defend against bad passwords within an organization. Password aging means that after a specified period (usually 90 days), the user is prompted to create a new password. The theory behind this is that if a user is forced to change his password periodically, a cracked password is only useful to an intruder for a limited amount of time. The downside to password aging, however, is that users are more likely to write their passwords down.

There are two primary programs used to specify password aging under Red Hat Enterprise Linux: the chage command or the graphical User Manager (system-config-users) application.

The -M option of the chage command specifies the maximum number of days the password is valid. For example, to set a user's password to expire in 90 days, use the following command:

chage -M 90 <username>

In the above command, replace <username> with the name of the user. To disable password expiration, it is traditional to use a value of 99999 after the -M option (this equates to a little over 273 years).

You can also use the chage command in interactive mode to modify multiple password aging and account details. Use the following command to enter interactive mode:

chage <username>

The following is a sample interactive session using this command:

[root@myServer ~]# chage davido

Changing the aging information for davido

Enter the new value, or press ENTER for the default

Minimum Password Age [0]: 10

Maximum Password Age [99999]: 90

Last Password Change (YYYY-MM-DD) [2006-08-18]:

Password Expiration Warning [7]:

Password Inactive [-1]:

Account Expiration Date (YYYY-MM-DD) [1969-12-31]:

[root@myServer ~]#

Refer to the man page for chage for more information on the available options.

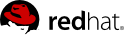

You can also use the graphical User Manager application to create password aging policies, as follows. Note: you need Administrator privileges to perform this procedure.

Click the menu on the Panel, point to and then click to display the User Manager. Alternatively, type the command system-config-users at a shell prompt.

Click the Users tab, and select the required user in the list of users.

Click Properties on the toolbar to display the User Properties dialog box (or choose on the menu).

Click the Password Info tab, and select the check box for Enable password expiration.

Enter the required value in the Days before change required field, and click OK.

2.1.4. Administrative Controls

When administering a home machine, the user must perform some tasks as the root user or by acquiring effective root privileges via a setuid program, such as sudo or su. A setuid program is one that operates with the user ID (UID) of the program's owner rather than the user operating the program. Such programs are denoted by an s in the owner section of a long format listing, as in the following example:

-rwsr-xr-x 1 root root 47324 May 1 08:09 /bin/su

The s may be upper case or lower case. If it appears as upper case, it means that the underlying permission bit has not been set.

For the system administrators of an organization, however, choices must be made as to how much administrative access users within the organization should have to their machine. Through a PAM module called pam_console.so, some activities normally reserved only for the root user, such as rebooting and mounting removable media are allowed for the first user that logs in at the physical console (refer to Managing Single Sign-On and Smart Cards for more information about the pam_console.so module.) However, other important system administration tasks, such as altering network settings, configuring a new mouse, or mounting network devices, are not possible without administrative privileges. As a result, system administrators must decide how much access the users on their network should receive.

2.1.4.1. Allowing Root Access

If the users within an organization are trusted and computer-literate, then allowing them root access may not be an issue. Allowing root access by users means that minor activities, like adding devices or configuring network interfaces, can be handled by the individual users, leaving system administrators free to deal with network security and other important issues.

On the other hand, giving root access to individual users can lead to the following issues:

Machine Misconfiguration — Users with root access can misconfigure their machines and require assistance to resolve issues. Even worse, they might open up security holes without knowing it.

Running Insecure Services — Users with root access might run insecure servers on their machine, such as FTP or Telnet, potentially putting usernames and passwords at risk. These services transmit this information over the network in plain text.

Running Email Attachments As Root — Although rare, email viruses that affect Linux do exist. The only time they are a threat, however, is when they are run by the root user.

2.1.4.2. Disallowing Root Access

If an administrator is uncomfortable allowing users to log in as root for these or other reasons, the root password should be kept secret, and access to runlevel one or single user mode should be disallowed through boot loader password protection (refer to

Section 2.1.2.2, “Boot Loader Passwords” for more information on this topic.)

Table 2.1. Methods of Disabling the Root Account

|

Method

|

Description

|

Effects

|

Does Not Affect

|

|---|

|

Changing the root shell.

|

Edit the /etc/passwd file and change the shell from /bin/bash to /sbin/nologin.

|

| Prevents access to the root shell and logs any such attempts. | | The following programs are prevented from accessing the root account: | · login | · gdm | · kdm | · xdm | · su | · ssh | · scp | · sftp |

|

| Programs that do not require a shell, such as FTP clients, mail clients, and many setuid programs. | | The following programs are not prevented from accessing the root account: | · sudo | | · FTP clients | | · Email clients |

|

|

Disabling root access via any console device (tty).

|

An empty /etc/securetty file prevents root login on any devices attached to the computer.

|

| Prevents access to the root account via the console or the network. The following programs are prevented from accessing the root account: | · login | · gdm | · kdm | · xdm | | · Other network services that open a tty |

|

| Programs that do not log in as root, but perform administrative tasks through setuid or other mechanisms. | | The following programs are not prevented from accessing the root account: | · su | · sudo | · ssh | · scp | · sftp |

|

|

Disabling root SSH logins.

|

Edit the /etc/ssh/sshd_config file and set the PermitRootLogin parameter to no.

|

| Prevents root access via the OpenSSH suite of tools. The following programs are prevented from accessing the root account: | · ssh | · scp | · sftp |

|

| This only prevents root access to the OpenSSH suite of tools. |

|

|

Use PAM to limit root access to services.

|

Edit the file for the target service in the /etc/pam.d/ directory. Make sure the pam_listfile.so is required for authentication.[]

|

| Prevents root access to network services that are PAM aware. | | The following services are prevented from accessing the root account: | | · FTP clients | | · Email clients | · login | · gdm | · kdm | · xdm | · ssh | · scp | · sftp | | · Any PAM aware services |

|

| Programs and services that are not PAM aware. |

|

2.1.4.2.1. Disabling the Root Shell

To prevent users from logging in directly as root, the system administrator can set the root account's shell to /sbin/nologin in the /etc/passwd file. This prevents access to the root account through commands that require a shell, such as the su and the ssh commands.

Programs that do not require access to the shell, such as email clients or the sudo command, can still access the root account.

2.1.4.2.2. Disabling Root Logins

To further limit access to the root account, administrators can disable root logins at the console by editing the /etc/securetty file. This file lists all devices the root user is allowed to log into. If the file does not exist at all, the root user can log in through any communication device on the system, whether via the console or a raw network interface. This is dangerous, because a user can log in to his machine as root via Telnet, which transmits the password in plain text over the network. By default, Red Hat Enterprise Linux's /etc/securetty file only allows the root user to log in at the console physically attached to the machine. To prevent root from logging in, remove the contents of this file by typing the following command:

echo > /etc/securetty

A blank /etc/securetty file does not prevent the root user from logging in remotely using the OpenSSH suite of tools because the console is not opened until after authentication.

2.1.4.2.3. Disabling Root SSH Logins

Root logins via the SSH protocol are disabled by default in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6; however, if this option has been enabled, it can be disabled again by editing the SSH daemon's configuration file (/etc/ssh/sshd_config). Change the line that reads:

PermitRootLogin yes

to read as follows:

PermitRootLogin no

For these changes to take effect, the SSH daemon must be restarted. This can be done via the following command:

kill -HUP `cat /var/run/sshd.pid`

2.1.4.2.4. Disabling Root Using PAM

PAM, through the /lib/security/pam_listfile.so module, allows great flexibility in denying specific accounts. The administrator can use this module to reference a list of users who are not allowed to log in. Below is an example of how the module is used for the vsftpd FTP server in the /etc/pam.d/vsftpd PAM configuration file (the \ character at the end of the first line in the following example is not necessary if the directive is on one line):

auth required /lib/security/pam_listfile.so item=user \

sense=deny file=/etc/vsftpd.ftpusers onerr=succeed

This instructs PAM to consult the /etc/vsftpd.ftpusers file and deny access to the service for any listed user. The administrator can change the name of this file, and can keep separate lists for each service or use one central list to deny access to multiple services.

If the administrator wants to deny access to multiple services, a similar line can be added to the PAM configuration files, such as /etc/pam.d/pop and /etc/pam.d/imap for mail clients, or /etc/pam.d/ssh for SSH clients.

For more information about PAM, refer to Managing Single Sign-On and Smart Cards.

2.1.4.3. Limiting Root Access

Rather than completely denying access to the root user, the administrator may want to allow access only via setuid programs, such as su or sudo.

2.1.4.3.1. The su Command

When a user executes the su command, they are prompted for the root password and, after authentication, is given a root shell prompt.

Once logged in via the su command, the user is the root user and has absolute administrative access to the system[]. In addition, once a user has become root, it is possible for them to use the su command to change to any other user on the system without being prompted for a password.

Because this program is so powerful, administrators within an organization may wish to limit who has access to the command.

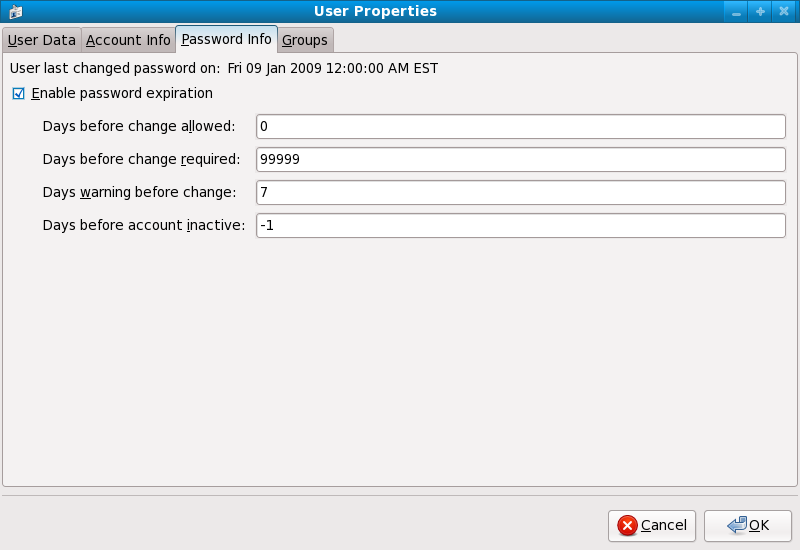

One of the simplest ways to do this is to add users to the special administrative group called wheel. To do this, type the following command as root:

usermod -G wheel <username>

In the previous command, replace <username> with the username you want to add to the wheel group.

You can also use the User Manager to modify group memberships, as follows. Note: you need Administrator privileges to perform this procedure.

Click the menu on the Panel, point to and then click to display the User Manager. Alternatively, type the command system-config-users at a shell prompt.

Click the Users tab, and select the required user in the list of users.

Click Properties on the toolbar to display the User Properties dialog box (or choose on the menu).

Open the PAM configuration file for su (/etc/pam.d/su) in a text editor and remove the comment # from the following line:

auth required /lib/security/$ISA/pam_wheel.so use_uid

This change means that only members of the administrative group wheel can use this program.

The root user is part of the wheel group by default.

2.1.4.3.2. The sudo Command

The sudo command offers another approach to giving users administrative access. When trusted users precede an administrative command with sudo, they are prompted for their own password. Then, when they have been authenticated and assuming that the command is permitted, the administrative command is executed as if they were the root user.

The basic format of the sudo command is as follows:

sudo <command>

In the above example, <command> would be replaced by a command normally reserved for the root user, such as mount.

Users of the sudo command should take extra care to log out before walking away from their machines since sudoers can use the command again without being asked for a password within a five minute period. This setting can be altered via the configuration file, /etc/sudoers.

The

sudo command allows for a high degree of flexibility. For instance, only users listed in the

/etc/sudoers configuration file are allowed to use the

sudo command and the command is executed in

the user's shell, not a root shell. This means the root shell can be completely disabled, as shown in

Section 2.1.4.2.1, “Disabling the Root Shell”.

The sudo command also provides a comprehensive audit trail. Each successful authentication is logged to the file /var/log/messages and the command issued along with the issuer's user name is logged to the file /var/log/secure.

Another advantage of the sudo command is that an administrator can allow different users access to specific commands based on their needs.

Administrators wanting to edit the sudo configuration file, /etc/sudoers, should use the visudo command.

To give someone full administrative privileges, type visudo and add a line similar to the following in the user privilege specification section:

juan ALL=(ALL) ALL

This example states that the user, juan, can use sudo from any host and execute any command.

The example below illustrates the granularity possible when configuring sudo:

%users localhost=/sbin/shutdown -h now

This example states that any user can issue the command /sbin/shutdown -h now as long as it is issued from the console.

The man page for sudoers has a detailed listing of options for this file.

2.1.5. Available Network Services

While user access to administrative controls is an important issue for system administrators within an organization, monitoring which network services are active is of paramount importance to anyone who administers and operates a Linux system.

Many services under Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 behave as network servers. If a network service is running on a machine, then a server application (called a daemon), is listening for connections on one or more network ports. Each of these servers should be treated as a potential avenue of attack.

2.1.5.1. Risks To Services

Network services can pose many risks for Linux systems. Below is a list of some of the primary issues:

Denial of Service Attacks (DoS) — By flooding a service with requests, a denial of service attack can render a system unusable as it tries to log and answer each request.

Distributed Denial of Service Attack (DDoS) — A type of DoS attack which uses multiple compromised machines (often numbering in the thousands or more) to direct a co-ordinated attack on a service, flooding it with requests and making it unusable.

Script Vulnerability Attacks — If a server is using scripts to execute server-side actions, as Web servers commonly do, a cracker can attack improperly written scripts. These script vulnerability attacks can lead to a buffer overflow condition or allow the attacker to alter files on the system.

Buffer Overflow Attacks — Services that connect to ports numbered 0 through 1023 must run as an administrative user. If the application has an exploitable buffer overflow, an attacker could gain access to the system as the user running the daemon. Because exploitable buffer overflows exist, crackers use automated tools to identify systems with vulnerabilities, and once they have gained access, they use automated rootkits to maintain their access to the system.

The threat of buffer overflow vulnerabilities is mitigated in Red Hat Enterprise Linux by ExecShield, an executable memory segmentation and protection technology supported by x86-compatible uni- and multi-processor kernels. ExecShield reduces the risk of buffer overflow by separating virtual memory into executable and non-executable segments. Any program code that tries to execute outside of the executable segment (such as malicious code injected from a buffer overflow exploit) triggers a segmentation fault and terminates.

Execshield also includes support for

No eXecute (

NX) technology on AMD64 platforms and

eXecute Disable (

XD) technology on Itanium and

Intel® 64 systems. These technologies work in conjunction with ExecShield to prevent malicious code from running in the executable portion of virtual memory with a granularity of 4KB of executable code, lowering the risk of attack from stealthy buffer overflow exploits.

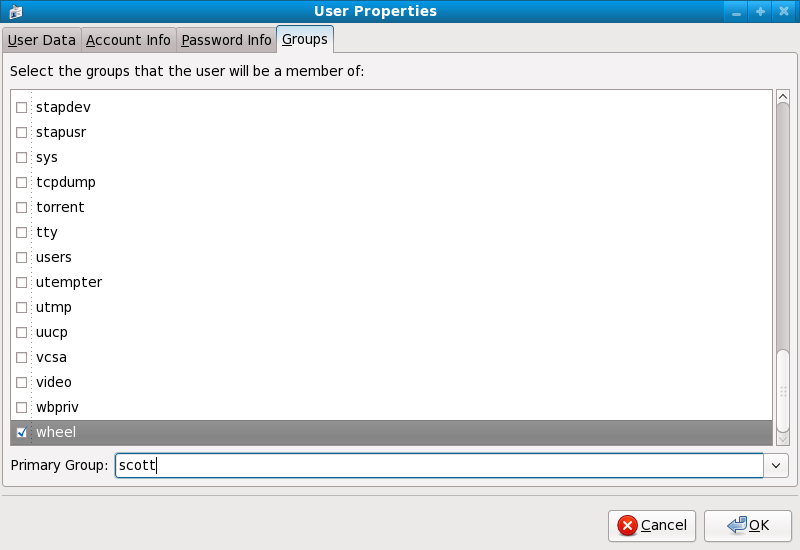

To limit exposure to attacks over the network, all services that are unused should be turned off.

2.1.5.2. Identifying and Configuring Services

To enhance security, most network services installed with Red Hat Enterprise Linux are turned off by default. There are, however, some notable exceptions:

cupsd — The default print server for Red Hat Enterprise Linux.

lpd — An alternative print server.

xinetd — A super server that controls connections to a range of subordinate servers, such as gssftp and telnet.

sendmail — The Sendmail

Mail Transport Agent (

MTA) is enabled by default, but only listens for connections from the

localhost.

sshd — The OpenSSH server, which is a secure replacement for Telnet.

When determining whether to leave these services running, it is best to use common sense and err on the side of caution. For example, if a printer is not available, do not leave cupsd running. The same is true for portmap. If you do not mount NFSv3 volumes or use NIS (the ypbind service), then portmap should be disabled.

2.1.5.3. Insecure Services

Potentially, any network service is insecure. This is why turning off unused services is so important. Exploits for services are routinely revealed and patched, making it very important to regularly update packages associated with any network service. Refer to

Section 1.5, “Security Updates” for more information.

Some network protocols are inherently more insecure than others. These include any services that:

Transmit Usernames and Passwords Over a Network Unencrypted — Many older protocols, such as Telnet and FTP, do not encrypt the authentication session and should be avoided whenever possible.

Transmit Sensitive Data Over a Network Unencrypted — Many protocols transmit data over the network unencrypted. These protocols include Telnet, FTP, HTTP, and SMTP. Many network file systems, such as NFS and SMB, also transmit information over the network unencrypted. It is the user's responsibility when using these protocols to limit what type of data is transmitted.

Remote memory dump services, like netdump, transmit the contents of memory over the network unencrypted. Memory dumps can contain passwords or, even worse, database entries and other sensitive information.

Other services like finger and rwhod reveal information about users of the system.

Examples of inherently insecure services include rlogin, rsh, telnet, and vsftpd.

FTP is not as inherently dangerous to the security of the system as remote shells, but FTP servers must be carefully configured and monitored to avoid problems. Refer to

Section 2.2.6, “Securing FTP” for more information about securing FTP servers.

Services that should be carefully implemented and behind a firewall include:

The next section discusses tools available to set up a simple firewall.

2.1.6. Personal Firewalls

After the necessary network services are configured, it is important to implement a firewall.

You should configure the necessary services and implement a firewall before connecting to the Internet or any other network that you do not trust.

Firewalls prevent network packets from accessing the system's network interface. If a request is made to a port that is blocked by a firewall, the request is ignored. If a service is listening on one of these blocked ports, it does not receive the packets and is effectively disabled. For this reason, care should be taken when configuring a firewall to block access to ports not in use, while not blocking access to ports used by configured services.

For most users, the best tool for configuring a simple firewall is the graphical firewall configuration tool which ships with Red Hat Enterprise Linux: the Firewall Configuration Tool (system-config-firewall). This tool creates broad iptables rules for a general-purpose firewall using a control panel interface.

For advanced users and server administrators, manually configuring a firewall with

iptables is probably a better option. Refer to

Section 2.5, “Firewalls” for more information. Refer to

Section 2.6, “IPTables” for a comprehensive guide to the

iptables command.