Creating Basic Zope Applications¶

This chapter will take you, step by step, through building a basic web application in Zope. As we go through the chapter, we will examine some of Zope’s main concepts at work. Using Zope Folder, Script (Python), and Page Template objects, we’ll create a simple website for an imaginary zoo: the “Zope Zoo”, of course!

We will develop the website as a Zope “instance-space” application. A discussion of instance space is at the end of this chapter, but for now it is enough to know that instance-space applications are the easiest and fastest kind to build, because we can do everything in our favorite web browser.

Goals for the Zope Zoo Web Site¶

As with any project, we first need to clarify our goals for the Zope Zoo application. The application’s primary goal is to create a website for the world-renowned Zope Zoo. Furthermore, we want to make the website easy to use and manage. Here are some things we’ll do:

- Enable web users to navigate the site easily, as if they were moving around a real zoo.

- Keep all our shared web layout tools, like a Cascading Style Sheet (CSS), in a single, easy-to-manage location.

- Design the website so that future site-wide changes are quick and easy to implement.

- Take advantage of Zope to create a dynamic website in which web pages build themselves “on the fly” when requested so that they are always up to date.

- Provide a simple file library of various documents that describe the animals.

Beginning with a Folder¶

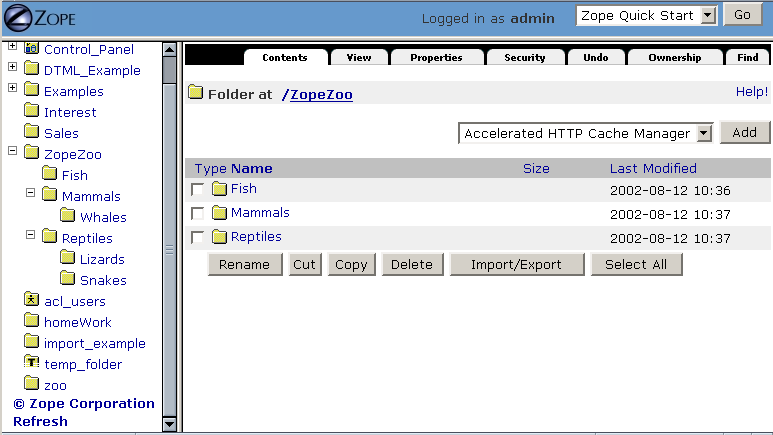

Zope Folder objects provide natural containers and organizers for web applications. A good way to start building an application is to create a new Folder to hold all the objects and subfolders related to the application.

Consider, for example, a Zope folder named Invoices to hold an application for managing invoices through the Web. The Invoices folder could contain both the logic objects - or “methods” - which allow you to add and edit invoices, as well as the actual data of the invoices. The Invoices folder thus becomes a small Zope application.

We begin building our Zope Zoo website application by creating a Zope Folder object to hold it all together in one place.

Step 1: Create ZopeZoo Folder¶

If you haven’t already, start your Zope installation and log into the Zope Management Interface (ZMI) using your favorite browser. (If you are not familiar with the ZMI, refer to the Installing and Starting Zope chapter.)

- Navigate to Zope’s top-level root folder.

- Use the Add list to create a new Folder.

- Give the new folder the Id ‘ZopeZoo’.

- Check Create public interface.

- Click Add.

(For now, we will ignore the optional Title fields.)

Modifying a Subsection of the Site¶

What if you want the reptile page to display something besides the welcome message? You can replace the index_html method in the reptile section with a more appropriate display method and still take advantage of the main template including navigation.

Step 12: Create index_html for the Reptile House¶

Go to the Reptile folder.

Add a new Page Template named ‘index_html’.

Give it some content more appropriate to reptiles:

<metal:macro metal:use-macro="context/z_zoo.pt/macros/page"> <metal:slot metal:fill-slot="headline"> <h1>The Reptile House</h1> </metal:slot> <metal:slot metal:fill-slot="content"> <p>Welcome to the Reptile House.</p> <p>We are open from 6pm to midnight Monday through Friday.</p> </metal:slot> </metal:macro>

Now take a look at the reptile page by going to the Reptile folder and clicking the View tab.

Since the index_html method in the Reptile folder uses the same macro as the main index_html, the reptile page still includes your navigation system.

Click on the Snakes link on the reptile page to see what the Snakes section looks like. The snakes page looks like the Reptiles page because the Snakes folder acquires its index_html display method from the Reptiles folder instead of from the ZopeZoo folder.

Creating a File Library¶

File libraries are common on websites since many sites distribute files of some sort. The old fashioned way to create a file library is to upload your files, then create a web page that contains links to those files. With Zope you can dynamically create links to files. When you upload, change or delete files, the file library’s links can change automatically.

Step 13: Creating Library Folder and some Files¶

- Add a new Folder to ZopeZoo with Id ‘Files’ and Title ‘File Library’.

- Within that folder, add two File objects called ‘DogGrooming’ and ‘HomeScienceExperiments’.

We don’t need any content within the files to test the library. Feel free to add some more files and upload some content.

Step 14: Adding index_html Script and Template¶

Within the Files folder, add this new Script (Python) with the Id ‘index_html’:

## Script (Python) "index_html" ##parameters= ## library_items = [] items = context.objectValues(['File']) for item in items: library_items.append( { 'title': item.title_or_id(), 'url': item.absolute_url(), 'modified': item.bobobase_modification_time().aCommon() } ) options = { 'library_items': tuple(library_items) } return options

Also add a new Page Template named ‘index_html.pt’ with this content:

<metal:macro metal:use-macro="context/z_zoo.pt/macros/page"> <metal:slot metal:fill-slot="content"> <table> <tr> <th width="300">File</th> <th>Last Modified</th> </tr> <tr> <td><a href="URL">TITLE</a></td> <td>MON DD, YYYY H:MM AM</td> </tr> </table> </metal:slot> </metal:macro>

This time the logic for our ‘index_html’ method will be more complex, so we should separate logic from presentation. We start with two unconnected objects: A Script (Python) to generate the results and a Page Template to present them as HTML page.

The script loops over ‘context.objectValues([‘File’])’, a list of all File objects in our Files folder, and appends for each file the needed values to the library_items list. Again the dynamic values are UPPERCASE in our mockup, so what we need are the file title, the url and the last modified date in a format like this: Mar 1, 1997 1:45 pm. Most Zope objects have the bobobase_modification_time method that returns a DateTime object. Looking at the API of DateTime, you’ll find that the aCommon method returns the format we want.

Later we will have more return values, so we store them in the options dictionary. Using the Test tab of the script you will see the returned dictionary contains all the dynamic content needed by our template.

The template uses again the page macro of z_zoo.pt. Unlike before there is only one ‘metal:fill-slot’ statement because we don’t want to override the headline slot. Go to the Test tab of the template to see how our file library will look like.

Step 15: Bringing Things Together¶

Replace the last line of the index_html script by this one:

return getattr(context, 'index_html.pt')(**options)

Look for this example table row in index_html.pt:

<tr> <td><a href="URL">TITLE</a></td> <td>MON DD, YYYY H:MM AM</td> </tr>

Replace it by that code:

<tr tal:repeat="item options/library_items"> <td><a href="URL" tal:attributes="href item/url" tal:content="item/title">TITLE</a></td> <td tal:content="item/modified">MON DD, YYYY H:MM AM</td> </tr>

Now our script calls the index_html.pt after doing all the computing and passes the resulting options dictionary to the template, which creates the HTML presentation of options. The Test tab of the template no longer works because it now depends on the script. Go to the Test tab of the script to see the result: The file library!

If you add another file, Zope will dynamically adjust the file library page. You may also want to try changing the titles of the files, uploading new files, or deleting some of the files.

Step 16: Making the Library Sortable¶

Find the table headers in index_html.pt:

<th width="300">File</th> <th>Last Modified</th>

Replace them with these dynamic table headers:

<th width="300"><a href="SORT_TITLE_URL" tal:omit-tag="not: options/sort_title_url" tal:attributes="href options/sort_title_url" >File</a></th> <th><a href="SORT_MODIFIED_URL" tal:omit-tag="not: options/sort_modified_url" tal:attributes="href options/sort_modified_url" >Last Modified</a></th>Extend index_html to make it look like this:

## Script (Python) "index_html" ##parameters=sort='title' ## library_items = [] items = context.objectValues(['File']) if sort == 'title': sort_on = ( ('title_or_id', 'cmp', 'asc'), ) sort_title_url = '' sort_modified_url = '%s?sort=modified' % context.absolute_url() else: sort_on = ( ('bobobase_modification_time', 'cmp', 'desc'), ) sort_title_url = '%s?sort=title' % context.absolute_url() sort_modified_url = '' items = sequence.sort(items, sort_on) for item in items: library_items.append( { 'title': item.title_or_id(), 'url': item.absolute_url(), 'modified': item.bobobase_modification_time().aCommon() } ) options = { 'sort_title_url': sort_title_url, 'sort_modified_url': sort_modified_url, 'library_items': tuple(library_items) } return getattr(context, 'index_html.pt')(**options)

The changes in the template are quite simple. If an url is provided, the column header becomes a link. If not, the ‘not:’ expression of the ‘tal:omit-tag’ statement is true and the ‘a’ tag is omitted. The script will always provide an url for the column that isn’t currently sorted.

Basically we have to extend the logic, so most changes are in the script. First of all we define an optional parameter sort. By default it is ‘title’, so if no value is passed in we sort by title. Sort criteria and urls depend on the sort parameter. We use the sort function of the built in sequence module to apply the sort criteria to the items list.

Now view the file library and click on the File and Last Modified links to sort the files. If there is a sort variable and if it has a value of modified then the files are sorted by modification time. Otherwise the files are sorted by title.

Building “Instance-Space” Applications¶

In Zope, there are a few ways to develop a web application. The simplest and fastest way, and the one we’ve been concentrating on thus far in this book, is to build an application in instance space. To understand the term “instance space”, we need to once again put on our “object orientation hats”.

When you create Zope objects by selecting them from the Zope “Add” list, you are creating instances of a class defined by someone else (see the Object Orientation chapter if you need to brush up on these terms). For example, when you add a Script (Python) object to your Zope database, you are creating an instance of the Script (Python) class. The Script (Python) class was written by a Zope Corporation engineer. When you select “Script (Python)” from the Add list, and you fill in the form to give an id and title and whatnot, and click the submit button on the form, Zope creates an instance of that class in the Folder of your choosing. Instances such as these are inserted into your Zope database and they live there until you delete them.

In the Zope application server, most object instances serve to perform presentation duties, logic duties, or content duties. You can “glue” these instances together to create basic Zope applications. Since these objects are really instances of a class, the term “instance space” is commonly used to describe the Zope root folder and all of its subfolders. “Building an application in instance space” is defined as the act of creating Zope object instances in this space and modifying them to act a certain way when they are executed.

Instance-space applications are typically created from common Zope objects. Script (Python) objects, Folders, Page Templates, and other Zope services can be glued together to build simple applications.

Instance-Space Applications vs. Python packages¶

In contrast to building applications in instance space, you may also build applications in Zope by building them as Python packages. Building an application as a package differs from creating applications in instance space inasmuch as the act of creating a package typically is more familiar to developers and does not constrain them in any way.

Building a package also typically allows you to more easily distribute an application to other people, and allows you to build objects that may more closely resemble your “problem space”.

Building a package is typically more complicated than building an “instance-space” application, so we get started here by describing how to build instance-space applications. When you find that it becomes difficult to maintain, extend, or distribute an instance-space application you’ve written, it’s probably time to reconsider rewriting it as a package.

The Next Step¶

This chapter shows how simple web applications can be made. Zope has many more features in addition to these, but these simple examples should get you started on create well managed, complex websites.

In the next chapter, we’ll see how the Zope security system lets Zope work with many different users at the same time and allows them to collaborate together on the same projects.