Multilayer Perceptron¶

Note

This section assumes the reader has already read through Classifying MNIST digits using Logistic Regression. Additionally, it uses the following new Theano functions and concepts: T.tanh, shared variables, basic arithmetic ops, T.grad, L1 and L2 regularization, floatX. If you intend to run the code on GPU also read GPU.

Note

The code for this section is available for download here.

The next architecture we are going to present using Theano is the

single-hidden-layer Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). An MLP can be viewed as a

logistic regression classifier where the input is first transformed using a

learnt non-linear transformation  . This transformation projects the

input data into a space where it becomes linearly separable. This intermediate

layer is referred to as a hidden layer. A single hidden layer is sufficient

to make MLPs a universal approximator. However we will see later on that

there are substantial benefits to using many such hidden layers, i.e. the very

premise of deep learning. See these course notes for an introduction to

MLPs, the back-propagation algorithm, and how to train MLPs.

. This transformation projects the

input data into a space where it becomes linearly separable. This intermediate

layer is referred to as a hidden layer. A single hidden layer is sufficient

to make MLPs a universal approximator. However we will see later on that

there are substantial benefits to using many such hidden layers, i.e. the very

premise of deep learning. See these course notes for an introduction to

MLPs, the back-propagation algorithm, and how to train MLPs.

This tutorial will again tackle the problem of MNIST digit classification.

The Model¶

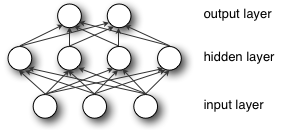

An MLP (or Artificial Neural Network - ANN) with a single hidden layer can be represented graphically as follows:

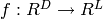

Formally, a one-hidden-layer MLP is a function  , where

, where  is the size of input vector

is the size of input vector  and

and  is

the size of the output vector

is

the size of the output vector  , such that, in matrix notation:

, such that, in matrix notation:

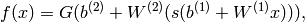

with bias vectors  ,

,  ; weight matrices

; weight matrices

,

,  and activation functions

and activation functions  and

and  .

.

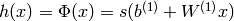

The vector  constitutes the hidden layer.

constitutes the hidden layer.

is the weight matrix connecting the input vector

to the hidden layer. Each column

is the weight matrix connecting the input vector

to the hidden layer. Each column  represents the weights

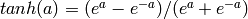

from the input units to the i-th hidden unit. Typical choices for

represents the weights

from the input units to the i-th hidden unit. Typical choices for  include

include  , with

, with  ,

or the logistic

,

or the logistic  function, with

function, with  . We will be using

. We will be using

in this tutorial because it typically yields to faster training

(and sometimes also to better local minima). Both the

in this tutorial because it typically yields to faster training

(and sometimes also to better local minima). Both the  and

and  are scalar-to-scalar functions but their natural

extension to vectors and tensors consists in applying them element-wise

(e.g. separately on each element of the vector, yielding a same-size vector).

are scalar-to-scalar functions but their natural

extension to vectors and tensors consists in applying them element-wise

(e.g. separately on each element of the vector, yielding a same-size vector).

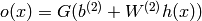

The output vector is then obtained as:  .

The reader should recognize the form we already used for

Classifying MNIST digits using Logistic Regression. As before,

class-membership probabilities can be obtained by choosing

.

The reader should recognize the form we already used for

Classifying MNIST digits using Logistic Regression. As before,

class-membership probabilities can be obtained by choosing  as the

as the

function (in the case of multi-class classification).

function (in the case of multi-class classification).

To train an MLP, we learn all parameters of the model, and here we use

Stochastic Gradient Descent with minibatches.

The set of parameters to learn is the set  . Obtaining the gradients

. Obtaining the gradients

can be achieved through the

backpropagation algorithm (a special case of the chain-rule of derivation).

Thankfully, since Theano performs automatic differentation, we will not need to

cover this in the tutorial !

can be achieved through the

backpropagation algorithm (a special case of the chain-rule of derivation).

Thankfully, since Theano performs automatic differentation, we will not need to

cover this in the tutorial !

Going from logistic regression to MLP¶

This tutorial will focus on a single-hidden-layer MLP. We start off by implementing a class that will represent a hidden layer. To construct the MLP we will then only need to throw a logistic regression layer on top.

class HiddenLayer(object):

def __init__(self, rng, input, n_in, n_out, W=None, b=None,

activation=T.tanh):

"""

Typical hidden layer of a MLP: units are fully-connected and have

sigmoidal activation function. Weight matrix W is of shape (n_in,n_out)

and the bias vector b is of shape (n_out,).

NOTE : The nonlinearity used here is tanh

Hidden unit activation is given by: tanh(dot(input,W) + b)

:type rng: numpy.random.RandomState

:param rng: a random number generator used to initialize weights

:type input: theano.tensor.dmatrix

:param input: a symbolic tensor of shape (n_examples, n_in)

:type n_in: int

:param n_in: dimensionality of input

:type n_out: int

:param n_out: number of hidden units

:type activation: theano.Op or function

:param activation: Non linearity to be applied in the hidden

layer

"""

self.input = input

The initial values for the weights of a hidden layer  should be uniformly

sampled from a symmetric interval that depends on the activation function. For

should be uniformly

sampled from a symmetric interval that depends on the activation function. For

activation function results obtained in [Xavier10] show that the

interval should be

activation function results obtained in [Xavier10] show that the

interval should be

![[-\sqrt{\frac{6}{fan_{in}+fan_{out}}},\sqrt{\frac{6}{fan_{in}+fan_{out}}}]](_images/math/1dfc4a270526d7a1f3411a25a81a580f05b61d84.png) , where

, where

is the number of units in the

is the number of units in the  -th layer,

and

-th layer,

and  is the number of units in the

is the number of units in the  -th layer. For

the sigmoid function the interval is

-th layer. For

the sigmoid function the interval is ![[-4\sqrt{\frac{6}{fan_{in}+fan_{out}}},4\sqrt{\frac{6}{fan_{in}+fan_{out}}}]](_images/math/67fb8dc5b0626d0673435da43542cab7e3453c38.png) .

This initialization ensures that, early in training, each neuron operates in a

regime of its activation function where information can easily be propagated

both upward (activations flowing from inputs to outputs) and backward

(gradients flowing from outputs to inputs).

.

This initialization ensures that, early in training, each neuron operates in a

regime of its activation function where information can easily be propagated

both upward (activations flowing from inputs to outputs) and backward

(gradients flowing from outputs to inputs).

# `W` is initialized with `W_values` which is uniformely sampled

# from sqrt(-6./(n_in+n_hidden)) and sqrt(6./(n_in+n_hidden))

# for tanh activation function

# the output of uniform if converted using asarray to dtype

# theano.config.floatX so that the code is runable on GPU

# Note : optimal initialization of weights is dependent on the

# activation function used (among other things).

# For example, results presented in [Xavier10] suggest that you

# should use 4 times larger initial weights for sigmoid

# compared to tanh

# We have no info for other function, so we use the same as

# tanh.

if W is None:

W_values = numpy.asarray(

rng.uniform(

low=-numpy.sqrt(6. / (n_in + n_out)),

high=numpy.sqrt(6. / (n_in + n_out)),

size=(n_in, n_out)

),

dtype=theano.config.floatX

)

if activation == theano.tensor.nnet.sigmoid:

W_values *= 4

W = theano.shared(value=W_values, name='W', borrow=True)

if b is None:

b_values = numpy.zeros((n_out,), dtype=theano.config.floatX)

b = theano.shared(value=b_values, name='b', borrow=True)

self.W = W

self.b = b

Note that we used a given non-linear function as the activation function of the hidden layer. By default this is tanh, but in many cases we might want

to use something else.

lin_output = T.dot(input, self.W) + self.b

self.output = (

lin_output if activation is None

else activation(lin_output)

)

If you look into theory this class implements the graph that computes

the hidden layer value  .

If you give this graph as input to the

.

If you give this graph as input to the LogisticRegression class,

implemented in the previous tutorial Classifying MNIST digits using Logistic Regression, you get the output

of the MLP. You can see this in the following short implementation of

the MLP class.

class MLP(object):

"""Multi-Layer Perceptron Class

A multilayer perceptron is a feedforward artificial neural network model

that has one layer or more of hidden units and nonlinear activations.

Intermediate layers usually have as activation function tanh or the

sigmoid function (defined here by a ``HiddenLayer`` class) while the

top layer is a softmax layer (defined here by a ``LogisticRegression``

class).

"""

def __init__(self, rng, input, n_in, n_hidden, n_out):

"""Initialize the parameters for the multilayer perceptron

:type rng: numpy.random.RandomState

:param rng: a random number generator used to initialize weights

:type input: theano.tensor.TensorType

:param input: symbolic variable that describes the input of the

architecture (one minibatch)

:type n_in: int

:param n_in: number of input units, the dimension of the space in

which the datapoints lie

:type n_hidden: int

:param n_hidden: number of hidden units

:type n_out: int

:param n_out: number of output units, the dimension of the space in

which the labels lie

"""

# Since we are dealing with a one hidden layer MLP, this will translate

# into a HiddenLayer with a tanh activation function connected to the

# LogisticRegression layer; the activation function can be replaced by

# sigmoid or any other nonlinear function

self.hiddenLayer = HiddenLayer(

rng=rng,

input=input,

n_in=n_in,

n_out=n_hidden,

activation=T.tanh

)

# The logistic regression layer gets as input the hidden units

# of the hidden layer

self.logRegressionLayer = LogisticRegression(

input=self.hiddenLayer.output,

n_in=n_hidden,

n_out=n_out

)

In this tutorial we will also use L1 and L2 regularization (see

L1 and L2 regularization). For this, we need to compute the L1 norm and the squared L2

norm of the weights  .

.

# L1 norm ; one regularization option is to enforce L1 norm to

# be small

self.L1 = (

abs(self.hiddenLayer.W).sum()

+ abs(self.logRegressionLayer.W).sum()

)

# square of L2 norm ; one regularization option is to enforce

# square of L2 norm to be small

self.L2_sqr = (

(self.hiddenLayer.W ** 2).sum()

+ (self.logRegressionLayer.W ** 2).sum()

)

# negative log likelihood of the MLP is given by the negative

# log likelihood of the output of the model, computed in the

# logistic regression layer

self.negative_log_likelihood = (

self.logRegressionLayer.negative_log_likelihood

)

# same holds for the function computing the number of errors

self.errors = self.logRegressionLayer.errors

# the parameters of the model are the parameters of the two layer it is

# made out of

self.params = self.hiddenLayer.params + self.logRegressionLayer.params

As before, we train this model using stochastic gradient descent with

mini-batches. The difference is that we modify the cost function to include the

regularization term. L1_reg and L2_reg are the hyperparameters

controlling the weight of these regularization terms in the total cost function.

The code that computes the new cost is:

# the cost we minimize during training is the negative log likelihood of

# the model plus the regularization terms (L1 and L2); cost is expressed

# here symbolically

cost = (

classifier.negative_log_likelihood(y)

+ L1_reg * classifier.L1

+ L2_reg * classifier.L2_sqr

)

We then update the parameters of the model using the gradient. This code is

almost identical to the one for logistic regression. Only the number of

parameters differ. To get around this ( and write code that could work

for any number of parameters) we will use the list of parameters that

we created with the model params and parse it, computing a gradient

at each step.

# compute the gradient of cost with respect to theta (sotred in params)

# the resulting gradients will be stored in a list gparams

gparams = [T.grad(cost, param) for param in classifier.params]

# specify how to update the parameters of the model as a list of

# (variable, update expression) pairs

# given two lists of the same length, A = [a1, a2, a3, a4] and

# B = [b1, b2, b3, b4], zip generates a list C of same size, where each

# element is a pair formed from the two lists :

# C = [(a1, b1), (a2, b2), (a3, b3), (a4, b4)]

updates = [

(param, param - learning_rate * gparam)

for param, gparam in zip(classifier.params, gparams)

]

# compiling a Theano function `train_model` that returns the cost, but

# in the same time updates the parameter of the model based on the rules

# defined in `updates`

train_model = theano.function(

inputs=[index],

outputs=cost,

updates=updates,

givens={

x: train_set_x[index * batch_size: (index + 1) * batch_size],

y: train_set_y[index * batch_size: (index + 1) * batch_size]

}

)

Putting it All Together¶

Having covered the basic concepts, writing an MLP class becomes quite easy. The code below shows how this can be done, in a way which is analogous to our previous logistic regression implementation.

"""

This tutorial introduces the multilayer perceptron using Theano.

A multilayer perceptron is a logistic regressor where

instead of feeding the input to the logistic regression you insert a

intermediate layer, called the hidden layer, that has a nonlinear

activation function (usually tanh or sigmoid) . One can use many such

hidden layers making the architecture deep. The tutorial will also tackle

the problem of MNIST digit classification.

.. math::

f(x) = G( b^{(2)} + W^{(2)}( s( b^{(1)} + W^{(1)} x))),

References:

- textbooks: "Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning" -

Christopher M. Bishop, section 5

"""

__docformat__ = 'restructedtext en'

import os

import sys

import timeit

import numpy

import theano

import theano.tensor as T

from logistic_sgd import LogisticRegression, load_data

# start-snippet-1

class HiddenLayer(object):

def __init__(self, rng, input, n_in, n_out, W=None, b=None,

activation=T.tanh):

"""

Typical hidden layer of a MLP: units are fully-connected and have

sigmoidal activation function. Weight matrix W is of shape (n_in,n_out)

and the bias vector b is of shape (n_out,).

NOTE : The nonlinearity used here is tanh

Hidden unit activation is given by: tanh(dot(input,W) + b)

:type rng: numpy.random.RandomState

:param rng: a random number generator used to initialize weights

:type input: theano.tensor.dmatrix

:param input: a symbolic tensor of shape (n_examples, n_in)

:type n_in: int

:param n_in: dimensionality of input

:type n_out: int

:param n_out: number of hidden units

:type activation: theano.Op or function

:param activation: Non linearity to be applied in the hidden

layer

"""

self.input = input

# end-snippet-1

# `W` is initialized with `W_values` which is uniformely sampled

# from sqrt(-6./(n_in+n_hidden)) and sqrt(6./(n_in+n_hidden))

# for tanh activation function

# the output of uniform if converted using asarray to dtype

# theano.config.floatX so that the code is runable on GPU

# Note : optimal initialization of weights is dependent on the

# activation function used (among other things).

# For example, results presented in [Xavier10] suggest that you

# should use 4 times larger initial weights for sigmoid

# compared to tanh

# We have no info for other function, so we use the same as

# tanh.

if W is None:

W_values = numpy.asarray(

rng.uniform(

low=-numpy.sqrt(6. / (n_in + n_out)),

high=numpy.sqrt(6. / (n_in + n_out)),

size=(n_in, n_out)

),

dtype=theano.config.floatX

)

if activation == theano.tensor.nnet.sigmoid:

W_values *= 4

W = theano.shared(value=W_values, name='W', borrow=True)

if b is None:

b_values = numpy.zeros((n_out,), dtype=theano.config.floatX)

b = theano.shared(value=b_values, name='b', borrow=True)

self.W = W

self.b = b

lin_output = T.dot(input, self.W) + self.b

self.output = (

lin_output if activation is None

else activation(lin_output)

)

# parameters of the model

self.params = [self.W, self.b]

# start-snippet-2

class MLP(object):

"""Multi-Layer Perceptron Class

A multilayer perceptron is a feedforward artificial neural network model

that has one layer or more of hidden units and nonlinear activations.

Intermediate layers usually have as activation function tanh or the

sigmoid function (defined here by a ``HiddenLayer`` class) while the

top layer is a softmax layer (defined here by a ``LogisticRegression``

class).

"""

def __init__(self, rng, input, n_in, n_hidden, n_out):

"""Initialize the parameters for the multilayer perceptron

:type rng: numpy.random.RandomState

:param rng: a random number generator used to initialize weights

:type input: theano.tensor.TensorType

:param input: symbolic variable that describes the input of the

architecture (one minibatch)

:type n_in: int

:param n_in: number of input units, the dimension of the space in

which the datapoints lie

:type n_hidden: int

:param n_hidden: number of hidden units

:type n_out: int

:param n_out: number of output units, the dimension of the space in

which the labels lie

"""

# Since we are dealing with a one hidden layer MLP, this will translate

# into a HiddenLayer with a tanh activation function connected to the

# LogisticRegression layer; the activation function can be replaced by

# sigmoid or any other nonlinear function

self.hiddenLayer = HiddenLayer(

rng=rng,

input=input,

n_in=n_in,

n_out=n_hidden,

activation=T.tanh

)

# The logistic regression layer gets as input the hidden units

# of the hidden layer

self.logRegressionLayer = LogisticRegression(

input=self.hiddenLayer.output,

n_in=n_hidden,

n_out=n_out

)

# end-snippet-2 start-snippet-3

# L1 norm ; one regularization option is to enforce L1 norm to

# be small

self.L1 = (

abs(self.hiddenLayer.W).sum()

+ abs(self.logRegressionLayer.W).sum()

)

# square of L2 norm ; one regularization option is to enforce

# square of L2 norm to be small

self.L2_sqr = (

(self.hiddenLayer.W ** 2).sum()

+ (self.logRegressionLayer.W ** 2).sum()

)

# negative log likelihood of the MLP is given by the negative

# log likelihood of the output of the model, computed in the

# logistic regression layer

self.negative_log_likelihood = (

self.logRegressionLayer.negative_log_likelihood

)

# same holds for the function computing the number of errors

self.errors = self.logRegressionLayer.errors

# the parameters of the model are the parameters of the two layer it is

# made out of

self.params = self.hiddenLayer.params + self.logRegressionLayer.params

# end-snippet-3

# keep track of model input

self.input = input

def test_mlp(learning_rate=0.01, L1_reg=0.00, L2_reg=0.0001, n_epochs=1000,

dataset='mnist.pkl.gz', batch_size=20, n_hidden=500):

"""

Demonstrate stochastic gradient descent optimization for a multilayer

perceptron

This is demonstrated on MNIST.

:type learning_rate: float

:param learning_rate: learning rate used (factor for the stochastic

gradient

:type L1_reg: float

:param L1_reg: L1-norm's weight when added to the cost (see

regularization)

:type L2_reg: float

:param L2_reg: L2-norm's weight when added to the cost (see

regularization)

:type n_epochs: int

:param n_epochs: maximal number of epochs to run the optimizer

:type dataset: string

:param dataset: the path of the MNIST dataset file from

http://www.iro.umontreal.ca/~lisa/deep/data/mnist/mnist.pkl.gz

"""

datasets = load_data(dataset)

train_set_x, train_set_y = datasets[0]

valid_set_x, valid_set_y = datasets[1]

test_set_x, test_set_y = datasets[2]

# compute number of minibatches for training, validation and testing

n_train_batches = train_set_x.get_value(borrow=True).shape[0] / batch_size

n_valid_batches = valid_set_x.get_value(borrow=True).shape[0] / batch_size

n_test_batches = test_set_x.get_value(borrow=True).shape[0] / batch_size

######################

# BUILD ACTUAL MODEL #

######################

print '... building the model'

# allocate symbolic variables for the data

index = T.lscalar() # index to a [mini]batch

x = T.matrix('x') # the data is presented as rasterized images

y = T.ivector('y') # the labels are presented as 1D vector of

# [int] labels

rng = numpy.random.RandomState(1234)

# construct the MLP class

classifier = MLP(

rng=rng,

input=x,

n_in=28 * 28,

n_hidden=n_hidden,

n_out=10

)

# start-snippet-4

# the cost we minimize during training is the negative log likelihood of

# the model plus the regularization terms (L1 and L2); cost is expressed

# here symbolically

cost = (

classifier.negative_log_likelihood(y)

+ L1_reg * classifier.L1

+ L2_reg * classifier.L2_sqr

)

# end-snippet-4

# compiling a Theano function that computes the mistakes that are made

# by the model on a minibatch

test_model = theano.function(

inputs=[index],

outputs=classifier.errors(y),

givens={

x: test_set_x[index * batch_size:(index + 1) * batch_size],

y: test_set_y[index * batch_size:(index + 1) * batch_size]

}

)

validate_model = theano.function(

inputs=[index],

outputs=classifier.errors(y),

givens={

x: valid_set_x[index * batch_size:(index + 1) * batch_size],

y: valid_set_y[index * batch_size:(index + 1) * batch_size]

}

)

# start-snippet-5

# compute the gradient of cost with respect to theta (sotred in params)

# the resulting gradients will be stored in a list gparams

gparams = [T.grad(cost, param) for param in classifier.params]

# specify how to update the parameters of the model as a list of

# (variable, update expression) pairs

# given two lists of the same length, A = [a1, a2, a3, a4] and

# B = [b1, b2, b3, b4], zip generates a list C of same size, where each

# element is a pair formed from the two lists :

# C = [(a1, b1), (a2, b2), (a3, b3), (a4, b4)]

updates = [

(param, param - learning_rate * gparam)

for param, gparam in zip(classifier.params, gparams)

]

# compiling a Theano function `train_model` that returns the cost, but

# in the same time updates the parameter of the model based on the rules

# defined in `updates`

train_model = theano.function(

inputs=[index],

outputs=cost,

updates=updates,

givens={

x: train_set_x[index * batch_size: (index + 1) * batch_size],

y: train_set_y[index * batch_size: (index + 1) * batch_size]

}

)

# end-snippet-5

###############

# TRAIN MODEL #

###############

print '... training'

# early-stopping parameters

patience = 10000 # look as this many examples regardless

patience_increase = 2 # wait this much longer when a new best is

# found

improvement_threshold = 0.995 # a relative improvement of this much is

# considered significant

validation_frequency = min(n_train_batches, patience / 2)

# go through this many

# minibatche before checking the network

# on the validation set; in this case we

# check every epoch

best_validation_loss = numpy.inf

best_iter = 0

test_score = 0.

start_time = timeit.default_timer()

epoch = 0

done_looping = False

while (epoch < n_epochs) and (not done_looping):

epoch = epoch + 1

for minibatch_index in xrange(n_train_batches):

minibatch_avg_cost = train_model(minibatch_index)

# iteration number

iter = (epoch - 1) * n_train_batches + minibatch_index

if (iter + 1) % validation_frequency == 0:

# compute zero-one loss on validation set

validation_losses = [validate_model(i) for i

in xrange(n_valid_batches)]

this_validation_loss = numpy.mean(validation_losses)

print(

'epoch %i, minibatch %i/%i, validation error %f %%' %

(

epoch,

minibatch_index + 1,

n_train_batches,

this_validation_loss * 100.

)

)

# if we got the best validation score until now

if this_validation_loss < best_validation_loss:

#improve patience if loss improvement is good enough

if (

this_validation_loss < best_validation_loss *

improvement_threshold

):

patience = max(patience, iter * patience_increase)

best_validation_loss = this_validation_loss

best_iter = iter

# test it on the test set

test_losses = [test_model(i) for i

in xrange(n_test_batches)]

test_score = numpy.mean(test_losses)

print((' epoch %i, minibatch %i/%i, test error of '

'best model %f %%') %

(epoch, minibatch_index + 1, n_train_batches,

test_score * 100.))

if patience <= iter:

done_looping = True

break

end_time = timeit.default_timer()

print(('Optimization complete. Best validation score of %f %% '

'obtained at iteration %i, with test performance %f %%') %

(best_validation_loss * 100., best_iter + 1, test_score * 100.))

print >> sys.stderr, ('The code for file ' +

os.path.split(__file__)[1] +

' ran for %.2fm' % ((end_time - start_time) / 60.))

if __name__ == '__main__':

test_mlp()

The user can then run the code by calling :

python code/mlp.py

The output one should expect is of the form :

Optimization complete. Best validation score of 1.690000 % obtained at iteration 2070000, with test performance 1.650000 %

The code for file mlp.py ran for 97.34m

On an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-2600K CPU @ 3.40GHz the code runs with approximately 10.3 epoch/minute and it took 828 epochs to reach a test error of 1.65%.

To put this into perspective, we refer the reader to the results section of this page.

Tips and Tricks for training MLPs¶

There are several hyper-parameters in the above code, which are not (and, generally speaking, cannot be) optimized by gradient descent. Strictly speaking, finding an optimal set of values for these hyper-parameters is not a feasible problem. First, we can’t simply optimize each of them independently. Second, we cannot readily apply gradient techniques that we described previously (partly because some parameters are discrete values and others are real-valued). Third, the optimization problem is not convex and finding a (local) minimum would involve a non-trivial amount of work.

The good news is that over the last 25 years, researchers have devised various rules of thumb for choosing hyper-parameters in a neural network. A very good overview of these tricks can be found in Efficient BackProp by Yann LeCun, Leon Bottou, Genevieve Orr, and Klaus-Robert Mueller. In here, we summarize the same issues, with an emphasis on the parameters and techniques that we actually used in our code.

Nonlinearity¶

Two of the most common ones are the  and the

and the  function. For

reasons explained in Section 4.4, nonlinearities that

are symmetric around the origin are preferred because they tend to produce

zero-mean inputs to the next layer (which is a desirable property).

Empirically, we have observed that the

function. For

reasons explained in Section 4.4, nonlinearities that

are symmetric around the origin are preferred because they tend to produce

zero-mean inputs to the next layer (which is a desirable property).

Empirically, we have observed that the  has better convergence

properties.

has better convergence

properties.

Weight initialization¶

At initialization we want the weights to be small enough around the origin

so that the activation function operates in its linear regime, where gradients are

the largest. Other desirable properties, especially for deep networks,

are to conserve variance of the activation as well as variance of back-propagated gradients from layer to layer.

This allows information to flow well upward and downward in the network and

reduces discrepancies between layers.

Under some assumptions, a compromise between these two constraints leads to the following

initialization: ![uniform[-\frac{\sqrt{6}}{\sqrt{fan_{in}+fan_{out}}},\frac{\sqrt{6}}{\sqrt{fan_{in}+fan_{out}}}]](_images/math/55b43defc5994f5f6f1a84be5266083e1201a623.png) for tanh and

for tanh and ![uniform[-4*\frac{\sqrt{6}}{\sqrt{fan_{in}+fan_{out}}},4*\frac{\sqrt{6}}{\sqrt{fan_{in}+fan_{out}}}]](_images/math/2ee204005e40cd0997def1f9d4171915c4df4dd8.png) for sigmoid. Where

for sigmoid. Where  is the number of inputs and

is the number of inputs and  the number of hidden units.

For mathematical considerations please refer to [Xavier10].

the number of hidden units.

For mathematical considerations please refer to [Xavier10].

Learning rate¶

There is a great deal of literature on choosing a good learning rate. The

simplest solution is to simply have a constant rate. Rule of thumb: try

several log-spaced values ( ) and narrow the

(logarithmic) grid search to the region where you obtain the lowest

validation error.

) and narrow the

(logarithmic) grid search to the region where you obtain the lowest

validation error.

Decreasing the learning rate over time is sometimes a good idea. One simple

rule for doing that is  where

where

is the initial rate (chosen, perhaps, using the grid search

technique explained above),

is the initial rate (chosen, perhaps, using the grid search

technique explained above),  is a so-called “decrease constant”

which controls the rate at which the learning rate decreases (typically, a

smaller positive number,

is a so-called “decrease constant”

which controls the rate at which the learning rate decreases (typically, a

smaller positive number,  and smaller) and

and smaller) and  is the

epoch/stage.

is the

epoch/stage.

Section 4.7 details procedures for choosing a learning rate for each parameter (weight) in our network and for choosing them adaptively based on the error of the classifier.

Regularization parameter¶

Typical values to try for the L1/L2 regularization parameter  are

are  . In the framework that we described so

far, optimizing this parameter will not lead to significantly better

solutions, but is worth exploring nonetheless.

. In the framework that we described so

far, optimizing this parameter will not lead to significantly better

solutions, but is worth exploring nonetheless.

(recall

(recall  is the number of hidden units).

is the number of hidden units).