Group communication uses the terms group and member. Members are part of a group. In the more common terminology, a member is a node and a groups is a cluster. We use these words interchangeably.

A node is a process, residing on some host. A cluster can have one or more nodes belonging to it. There can be multiple nodes on the same host, and all may or may not be part of the same cluster.

JGroups is toolkit for reliable group communication. Processes can join a group, send messages to all members or single members and receive messages from members in the group. The system keeps track of the members in every group, and notifies group members when a new member joins, or an existing member leaves or crashes. A group is identified by its name. Groups do not have to be created explicitly; when a process joins a non-existing group, that group will be created automatically. Member processes of a group can be located on the same host, within the same LAN, or across a WAN. A member can be part of multiple groups.

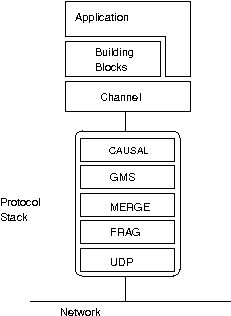

The architecture of JGroups is shown in Figure 1.1, “The architecture of JGroups”.

It consists of 3 parts: (1) the Channel API used by application programmers to build reliable group communication applications, (2) the building blocks, which are layered on top of the channel and provide a higher abstraction level and (3) the protocol stack, which implements the properties specified for a given channel.

This document describes how to install and use JGroups, ie. the Channel API and the building blocks. The targeted audience is application programmers who want to use JGroups to build reliable distributed programs that need group communication. Programmers who want to implement their own protocols to be used with JGroups should consult the Programmer's Guide for more details about the architecture and implementation of JGroups.

A channel is connected to a protocol stack. Whenever the application sends a message, the channel passes it on to the protocol stack, which passes it to the topmost protocol. The protocol processes the message and the passes it on to the protocol below it. Thus the message is handed from protocol to protocol until the bottom protocol puts it on the network. The same happens in the reverse direction: the bottom (transport) protocol listens for messages on the network. When a message is received it will be handed up the protocol stack until it reaches the channel. The channel stores the message in a queue until the application consumes it.

When an application connects to the channel, the protocol stack will be started, and when it disconnects the stack will be stopped. When the channel is closed, the stack will be destroyed, releasing its resources.

The following three sections give an overview of channels, building blocks and the protocol stack.

To join a group and send messages, a process has to create a channel and connect to it using the group name (all channels with the same name form a group). The channel is the handle to the group. While connected, a member may send and receive messages to/from all other group members. The client leaves a group by disconnecting from the channel. A channel can be reused: clients can connect to it again after having disconnected. However, a channel allows only 1 client to be connected at a time. If multiple groups are to be joined, multiple channels can be created and connected to. A client signals that it no longer wants to use a channel by closing it. After this operation, the channel cannot be used any longer.

Each channel has a unique address. Channels always know who the other members are in the same group: a list of member addresses can be retrieved from any channel. This list is called a view. A process can select an address from this list and send a unicast message to it (also to itself), or it may send a multicast message to all members of the current view. Whenever a process joins or leaves a group, or when a crashed process has been detected, a new view is sent to all remaining group members. When a member process is suspected of having crashed, a suspicion message is received by all non-faulty members. Thus, channels receive regular messages, view messages and suspicion messages. A client may choose to turn reception of views and suspicions on/off on a channel basis.

Channels are similar to BSD sockets: messages are stored in a channel until a client removes the next one (pull-principle). When no message is currently available, a client is blocked until the next available message has been received.

There is currently only one implementation of Channel: JChannel.

The properties of a channel are typically defined in an XML file, but JGroups also allows for configuration through simple strings, URIs, DOM trees or even programming.

The Channel API and its related classes is described in Chapter 3, API.

Channels are simple and primitive. They offer the bare functionality of group communication, and have on purpose been designed after the simple model of BSD sockets, which are widely used and well understood. The reason is that an application can make use of just this small subset of JGroups, without having to include a whole set of sophisticated classes, that it may not even need. Also, a somewhat minimalistic interface is simple to understand: a client needs to know about 12 methods to be able to create and use a channel (and oftentimes will only use 3-4 methods frequently).

Channels provide asynchronous message sending/reception, somewhat similar to UDP. A message sent is essentially put on the network and the send() method will return immediately. Conceptual requests, or responses to previous requests, are received in undefined order, and the application has to take care of matching responses with requests.

Also, an application has to actively retrieve messages from a channel (pull-style); it is not notified when a message has been received. Note that pull-style message reception often needs another thread of execution, or some form of event-loop, in which a channel is periodically polled for messages.

JGroups offers building blocks that provide more sophisticated APIs on top of a Channel. Building blocks either create and use channels internally, or require an existing channel to be specified when creating a building block. Applications communicate directly with the building block, rather than the channel. Building blocks are intended to save the application programmer from having to write tedious and recurring code, e.g. request-response correlation.

Building blocks are described in Chapter 4, Building Blocks.

The protocol stack containins a number of protocol layers in a bidirectional list. All messages sent and received over the channel have to pass through the protocol stack. Every layer may modify, reorder, pass or drop a message, or add a header to a message. A fragmentation layer might break up a message into several smaller messages, adding a header with an id to each fragment, and re-assemble the fragments on the receiver's side.

The composition of the protocol stack, i.e. its layers, is determined by the creator of the channel: an XML file defines the layers to be used (and the parameters for each layer). This string might be interpreted differently by each channel implementation; in JChannel it is used to create the stack, depending on the protocol names given in the property.

Knowledge about the protocol stack is not necessary when only using channels in an application. However, when an application wishes to ignore the default properties for a protocol stack, and configure their own stack, then knowledge about what the individual layers are supposed to do is needed. Although it is syntactically possible to stack any layer on top of each other (they all have the same interface), this wouldn't make sense semantically in most cases.

A header is a custom bit of information that can be added to each message. JGroups uses headers extensively, for example to add sequence numbers to each message (NAKACK and UNICAST), so that those messages can be delivered in the order in which they were sent.