Matrices and transforms¶

Introduction¶

Before reading this tutorial, it is advised to read the previous one about Vector math as this one is a direct continuation.

This tutorial will be about transformations and will cover a little about matrices (but not in-depth).

Transformations are most of the time applied as translation, rotation and scale so they will be considered as priority here.

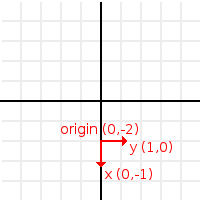

Oriented coordinate system (OCS)¶

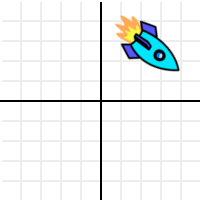

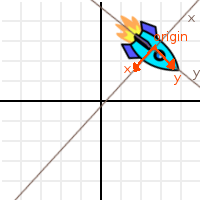

Imagine we have a spaceship somewhere in space. In Godot this is easy, just move the ship somewhere and rotate it:

Ok, so in 2D this looks simple, a position and an angle for a rotation. But remember, we are grown ups here and don’t use angles (plus, angles are not really even that useful when working in 3D).

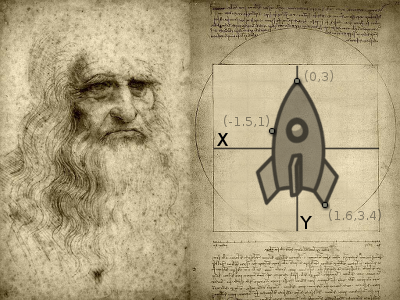

We should realize that at some point, someone designed this spaceship. Be it for 2D in a drawing such as Paint.net, Gimp, Photoshop, etc. or in 3D through a 3D DCC tool such as Blender, Max, Maya, etc.

When it was designed, it was not rotated. It was designed in it’s own coordinate system.

This means that the tip of the ship has a coordinate, the fin has another, etc. Be it in pixels (2D) or vertices (3D).

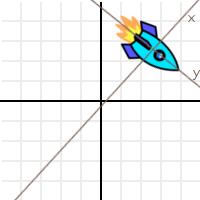

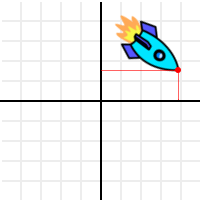

So, let’s recall again that the ship was somewhere in space:

How did it get there? What moved it and rotated it from the place it was designed to it’s current position? The answer is... a transform, the ship was transformed from their original position to the new one. This allows the ship to be displayed where it is.

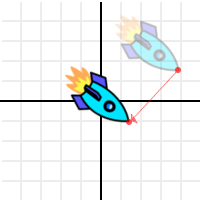

But transform is too generic of a term to describe this process. To solve this puzzle, we will superimpose the ship’s original design position at their current position:

So, we can see that the “design space” has been transformed too. How can we best represent this transformation? Let’s use 3 vectors for this (in 2D), a unit vector pointing towards X positive, a unit vector pointing towards Y positive and a translation.

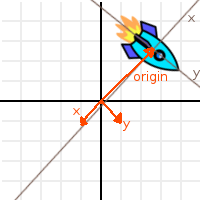

Let’s call the 3 vectors “X”, “Y” and “Origin”, and let’s also superimpose them over the ship so it makes more sense:

Ok, this is nicer, but it still does not make sense. What do X,Y and Origin have to do with how the ship got there?

Well, let’s take the point from top tip of the ship as reference:

And let’s apply the following operation to it (and to all the points in the ship too, but we’ll track the top tip as our reference point):

var new_pos = pos - origin

Doing this to the selected point will move it back to the center:

This was expected, but then let’s do something more interesting. Use the dot product of X and the point, and add it to the dot product of Y and the point:

var final_pos = x.dot(new_pos) + y.dot(new_pos)

Then what we have is.. wait a minute, it’s the ship in it’s design position!

How did this black magic happen? The ship was lost in space, and now it’s back home!

It might seem strange, but it does have plenty of logic. Remember, as we have seen in the Vector math, what happened is that the distance to X axis, and the distance to Y axis were computed. Calculating distance in a direction or plane was one of the uses for the dot product. This was enough to obtain back the design coordinates for every point in the ship.

So, what he have been working with so far (with X, Y and Origin) is an Oriented Coordinate System*. X an Y are the **Basis*, and *Origin* is the offset.

Basis¶

We know what the Origin is. It’s where the 0,0 (origin) of the design coordinate system ended up after being transformed to a new position. This is why it’s called Origin, But in practice, it’s just an offset to the new position.

The Basis is more interesting. The basis is the direction of X and Y in the OCS from the new, transformed location. It tells what has changed, in either 2D or 3D. The Origin (offset) and Basis (direction) communicate “Hey, the original X and Y axes of your design are right here, pointing towards these directions.”

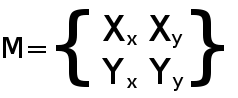

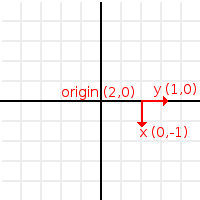

So, let’s change the representation of the basis. Instead of 2 vectors, let’s use a matrix.

The vectors are up there in the matrix, horizontally. The next problem now is that.. what is this matrix thing? Well, we’ll assume you’ve never heard of a matrix.

Transforms in Godot¶

This tutorial will not explain matrix math (and their operations) in depth, only its practical use. There is plenty of material for that, which should be a lot simpler to understand after completing this tutorial. We’ll just explain how to use transforms.

Matrix32¶

Matrix32 is a 3x2 matrix. It has 3 Vector2 elements and it’s used for 2D. The “X” axis is the element 0, “Y” axis is the element 1 and “Origin” is element 2. It’s not divided in basis/origin for convenience, due to it’s simplicity.

var m = Matrix32()

var x = m[0] # 'X'

var y = m[1] # 'Y'

var o = m[2] # 'Origin'

Most operations will be explained with this datatype (Matrix32), but the same logic applies to 3D.

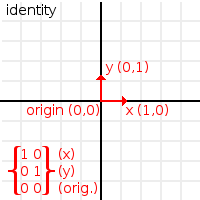

Identity¶

By default, Matrix32 is created as an “identity” matrix. This means:

- ‘X’ Points right: Vector2(1,0)

- ‘Y’ Points up (or down in pixels): Vector2(0,1)

- ‘Origin’ is the origin Vector2(0,0)

It’s easy to guess that an identity matrix is just a matrix that aligns the transform to it’s parent coordinate system. It’s an OCS that hasn’t been translated, rotated or scaled. All transform types in Godot are created with identity.

Operations¶

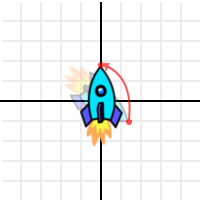

Rotation¶

Rotating Matrix32 is done by using the “rotated” function:

var m = Matrix32()

m = m.rotated(PI/2) # rotate 90°

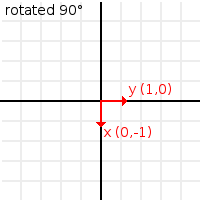

Translation¶

There are two ways to translate a Matrix32, the first one is just moving the origin:

# Move 2 units to the right

var m = Matrix32()

m = m.rotated(PI/2) # rotate 90°

m[2]+=Vector2(2,0)

This will always work in global coordinates.

If instead, translation is desired in local coordinates of the matrix (towards where the basis is oriented), there is the Matrix32.translated() method:

# Move 2 units towards where the basis is oriented

var m = Matrix32()

m = m.rotated(PI/2) # rotate 90°

m=m.translated( Vector2(2,0) )

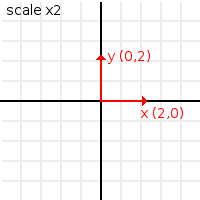

Scale¶

A matrix can be scaled too. Scaling will multiply the basis vectors by a vector (X vector by x component of the scale, Y vector by y component of the scale). It will leave the origin alone:

# Make the basis twice it's size.

var m = Matrix32()

m = m.scaled( Vector2(2,2) )

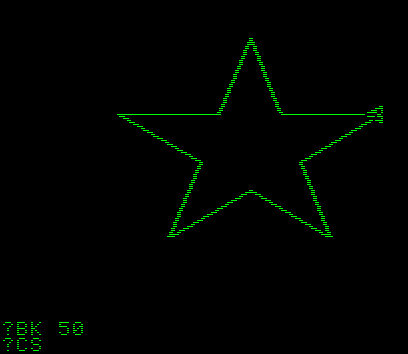

These kind of operations in matrices are accumulative. It means every one starts relative to the previous one. For those that have been living on this planet long enough, a good reference of how transform works is this:

A matrix is used similarly to a turtle. The turtle most likely had a matrix inside (and you are likely learning this may years after discovering Santa is not real).

Transform¶

Transform is the act of switching between coordinate systems. To convert a position (either 2D or 3D) from “designer” coordinate system to the OCS, the “xform” method is used.

var new_pos = m.xform(pos)

And only for basis (no translation):

var new_pos = m.basis_xform(pos)

Post - multiplying is also valid:

var new_pos = m * pos

Inverse transform¶

To do the opposite operation (what we did up there with the rocket), the “xform_inv” method is used:

var new_pos = m.xform_inv(pos)

Only for Basis:

var new_pos = m.basis_xform_inv(pos)

Or pre-multiplication:

var new_pos = pos * m

Orthonormal matrices¶

However, if the Matrix has been scaled (vectors are not unit length), or the basis vectors are not orthogonal (90°), the inverse transform will not work.

In other words, inverse transform is only valid in orthonormal matrices. For this, these cases an affine inverse must be computed.

The transform, or inverse transform of an identity matrix will return the position unchanged:

# Does nothing, pos is unchanged

pos = Matrix32().xform(pos)

Affine inverse¶

The affine inverse is a matrix that does the inverse operation of another matrix, no matter if the matrix has scale or the axis vectors are not orthogonal. The affine inverse is calculated with the affine_inverse() method:

var mi = m.affine_inverse()

var pos = m.xform(pos)

pos = mi.xform(pos)

# pos is unchanged

If the matrix is orthonormal, then:

# if m is orthonormal, then

pos = mi.xform(pos)

# is the same is

pos = m.xform_inv(pos)

Matrix multiplication¶

Matrices can be multiplied. Multiplication of two matrices “chains” (concatenates) their transforms.

However, as per convention, multiplication takes place in reverse order.

Example:

var m = more_transforms * some_transforms

To make it a little clearer, this:

pos = transform1.xform(pos)

pos = transform2.xform(pos)

Is the same as:

# note the inverse order

pos = (transform2 * transform1).xform(pos)

However, this is not the same:

# yields a different results

pos = (transform1 * transform2).xform(pos)

Because in matrix math, A + B is not the same as B + A.

Multiplication by inverse¶

Multiplying a matrix by it’s inverse, results in identity

# No matter what A is, B will be identity

B = A.affine_inverse() * A

Multiplication by identity¶

Multiplying a matrix by identity, will result in the unchanged matrix:

# B will be equal to A

B = A * Matrix32()

Matrix tips¶

When using a transform hierarchy, remember that matrix multiplication is reversed! To obtain the global transform for a hierarchy, do:

var global_xform = parent_matrix * child_matrix

For 3 levels:

# due to reverse order, parenthesis are needed

var global_xform = gradparent_matrix + (parent_matrix + child_matrix)

To make a matrix relative to the parent, use the affine inverse (or regular inverse for orthonormal matrices).

# transform B from a global matrix to one local to A

var B_local_to_A = A.affine_inverse() * B

Revert it just like the example above:

# transform back local B to global B

var B = A * B_local_to_A

OK, hopefully this should be enough! Let’s complete the tutorial by moving to 3D matrices.

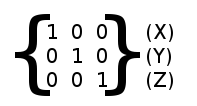

Matrices & transforms in 3D¶

As mentioned before, for 3D, we deal with 3 Vector3 vectors for the rotation matrix, and an extra one for the origin.

Matrix3¶

Godot has a special type for a 3x3 matrix, named Matrix3. It can be used to represent a 3D rotation and scale. Sub vectors can be accessed as:

var m = Matrix3()

var x = m[0] # Vector3

var y = m[1] # Vector3

var z = m[2] # Vector3

Or, alternatively as:

var m = Matrix3()

var x = m.x # Vector3

var y = m.y # Vector3

var z = m.z # Vector3

Matrix3 is also initialized to Identity by default:

Rotation in 3D¶

Rotation in 3D is more complex than in 2D (translation and scale are the same), because rotation is an implicit 2D operation. To rotate in 3D, an axis, must be picked. Rotation, then, happens around this axis.

The axis for the rotation must be a normal vector. As in, a vector that can point to any direction, but length must be one (1.0).

#rotate in Y axis

var m3 = Matrix3()

m3 = m3.rotated( Vector3(0,1,0), PI/2 )

Transform¶

To add the final component to the mix, Godot provides the Transform type. Transform has two members:

Any 3D transform can be represented with Transform, and the separation of basis and origin makes it easier to work translation and rotation separately.

An example:

var t = Transform()

pos = t.xform(pos) # transform 3D position

pos = t.basis.xform(pos) # (only rotate)

pos = t.origin + pos (only translate)