Sound

This chapter will demonstrate how to use the sound features that you'll find in openFrameworks, as well as some techniques you can use to generate and process sound.

Here's a quick overview of the classes you can use to work with sound in openFrameworks:

ofSoundPlayer provides simple access to sound files, allowing you to easily load and play sounds, add sound effects to an app and extract some data about the file's sound as it's playing.

ofSoundStream gives you access to the computer's sound hardware, allowing you to generate your own sound as well as react to sound coming into your computer from something like a microphone or line-in jack.

ofSoundBuffer is used to store a sequence of audio samples and perform audio-related things on said samples (like resampling). This is new in openFrameworks 0.9.0.

Getting Started With Sound Files

Playing a sound file is only a couple lines of code in openFrameworks. Just point an ofSoundPlayer at a file stored in your app's data folder and tell it to play.

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp {

// ... other things ...

ofSoundPlayer soundPlayer;

};

void ofApp::setup() {

soundPlayer.loadSound("song.mp3");

soundPlayer.play();

}This is fine for adding some background music or ambiance to your app, but ofSoundPlayer comes with a few extra features that are particularly handy for handling sound effects.

"Multiplay" allows you to have a file playing several times simultaneously. This is great for any sound effect which might end up getting triggered rapidly, so you don't get stuck with an unnatural cutoff as the player's playhead abruptly jumps back to the beginning of the file. Multiplay isn't on by default. Use soundPlayer.setMultiPlay(true) to enable it. Then you can get natural sound effect behaviour with dead-simple trigger logic like this:

if ( thingHappened ) {

soundPlayer.play();

}Another feature built-in to ofSoundPlayer is speed control. If you set the speed faster than normal, the sound's pitch will rise accordingly, and vice-versa (just like a vinyl record). Playback speed is defined relative to "1", so "0.5" is half speed and "2" is double speed.

Speed control and multiplay are made for each other. Making use of both simultaneously can really extend the life of a single sound effect file. Every time you change a sound player's playback speed with multiplay enabled, previously triggered sound effects continue on unaffected. So, by extending the above trigger logic to something like...

if( thingHappened ) {

soundPlayer.setSpeed(ofRandom(0.8, 1.2));

soundPlayer.play();

}...you'll introduce a bit of unique character to each instance of the sound.

One other big feature of ofSoundPlayer is easy spectrum access. On the desktop platforms, you can make use of ofSoundGetSpectrum() to get the frequency domain representation of the sound coming from all of the currently active ofSoundPlayers in your app. An explanation of the frequency domain is coming a little later in this chapter, but running the openFrameworks soundPlayerFFTExample will give you the gist.

Ultimately, ofSoundPlayer is a tradeoff between ease-of-use and control. You get access to multiplay and pitch-shifted playback but you don't get extremely precise control or access to the individual samples in the sound file. For this level of control, ofSoundStream is the tool for the job.

Getting Started With the Sound Stream

ofSoundStream is the gateway to the audio hardware on your computer, such as the microphone and the speakers. If you want to have your app react to live audio input or generate sound on the fly, this is the section for you!

You may never have to use the ofSoundStream directly, but it's the object that manages the resources needed to trigger audioOut() and audioIn() on your app. These two functions are optional members of your ofApp, like keyPressed(), windowResized() and mouseMoved(). They will start being called once you implement them and initiate the sound stream. Here's the basic structure for a sound-producing openFrameworks app:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp {

// ... other things ...

void audioOut( float * output, int bufferSize, int nChannels );

double phase;

};

void ofApp::setup() {

phase = 0;

ofSoundStreamSetup(2, 0); // 2 output channels (stereo), 0 input channels

}

void ofApp::audioOut( float * output, int bufferSize, int nChannels ) {

for(int i = 0; i < bufferSize * nChannels; i += 2) {

float sample = sin(phase); // generating a sine wave sample

output[i] = sample; // writing to the left channel

output[i+1] = sample; // writing to the right channel

phase += 0.05;

}

}When producing or receiving audio, the format is floating point numbers between -1 and 1 (the reason for this is coming a little later in this chapter). The sound will arrive in your app in the form of buffers. Buffers are just arrays, but the term "buffer" implies that each time you get a new one, it represents the chunk of time after the previous buffer. The reason openFrameworks asks you for buffers (instead of individual samples) is due to the overhead involved in shuttling data from your program to the audio hardware, and is a little outside the scope of this book.

The buffer size is adjustable, but it's usually a good idea to leave it at the default. The default isn't any number in particular, but will usually be whatever the hardware on your computer prefers. In practice, this is probably about 512 samples per buffer (256 and 1024 are other common buffer sizes).

Sound buffers in openFrameworks are interleaved meaning that the samples for each channel are right next to each other, like:

[Left] [Right] [Left] [Right] ...This means you access individual sound channels in much the same way as accessing different colours in an ofPixels object (i.e. buffer[i] for the left channel, buffer[i + 1] for the right channel). The total size of the buffer you get in audioIn() / audioOut() can be calculated with bufferSize * nChannels.

An important caveat to keep in mind when dealing with ofSoundStream is that audio callbacks like audioIn() and audioOut() will be called on a seperate thread from the standard setup(), update(), draw() functions. This means that if you'd like to share any data between (for example) update() and audioOut(), you need to make use of an ofMutex to keep both threads from getting in each others' way. You can see this in action a little later in this chapter, or check out the threads chapter for a more in-depth explanation.

In openFrameworks 0.9.0, there's a new class ofSoundBuffer that can be used in audioOut() instead of the float * output, int bufferSize, int channels form. In this case, the audioOut() function above can be rewritten to the simpler form:

void ofApp::audioOut(ofSoundBuffer &outBuffer) {

for(int i = 0; i < outBuffer.size(); i += 2) {

float sample = sin(phase); // generating a sine wave sample

outBuffer[i] = sample; // writing to the left channel

outBuffer[i + 1] = sample; // writing to the right channel

phase += 0.05;

}

}Why -1 to 1?

In order to understand why openFrameworks chooses to represent sound as a continuous stream of float values ranging from -1 to 1, it'll be helpful to know how sound is created on a physical level.

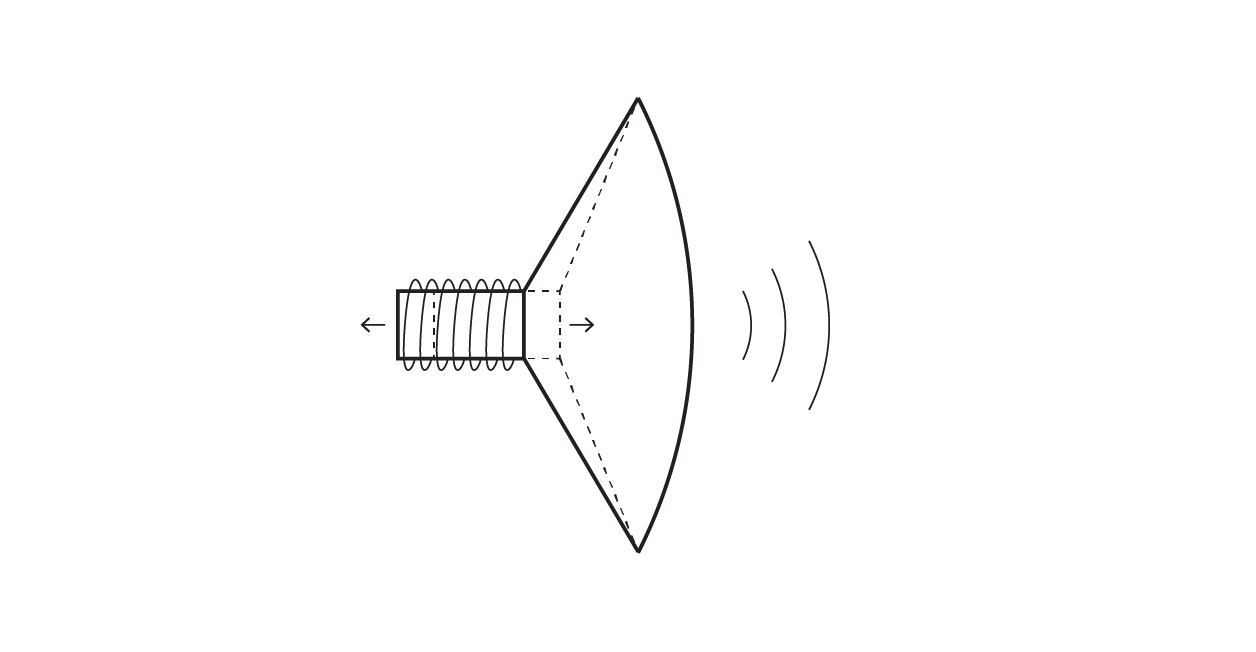

At the most basic level, a speaker consists of a cone and an electromagnet. The electromagnet pushes and pulls the cone to create vibrations in air pressure. These vibrations make their way to your ears, where they are interpreted as sound. When the electromagnet is off, the cone is simply "at rest", neither pulled in or pushed out. A basic microphone works much the same way: allowing air pressure to vibrate an object held in place by a magnet, thereby creating an electrical signal.

From the perspective of an openFrameworks app, it's not important what the sound hardware's specific voltages are. All that really matters is that the speaker cone is being driven between its "fully pushed out" and "fully pulled in" positions, which are represented as 1 and -1. This is similar to the notion of "1" as a representation of 100% as described in the animation chapter, though sound introduces the concept of -100%.

Some other systems use an integer-based representation, moving between something like -65535 and +65535 with 0 still being the representation of "at rest". The Web Audio API provides an unsigned 8-bit representation, which ranges between 0 and 255 with 127 being "at rest".

A major way that sound differs from visual content is that there isn't really a "static" representation of sound. For example, if you were dealing with an OpenGL texture which represents 0 as "black" and 1 as "white", you could fill the texture with all 0s or all 1s and end up with a static image of "black" or "white" respectively. This is not the case with sound. If you were to create a sound buffer of all 0s, all 1s, all -1s, or any single number, they would all sound like exactly the same thing: nothing at all.

Technically, you'd probably hear a pop right at the beginning as the speaker moves from the "at rest" position to whatever number your buffer is full of, but the remainder of your sound buffer would just be silence.

This is because what you actually hear is the changes in values over time. Any individual sample in a buffer doesn't really have a sound on its own. What you hear is the difference between the sample and the one before it. For instance, a sound's "loudness" isn't necessarily related to how "big" the individual numbers in a buffer are. A sine wave which oscillates between 0.9 and 1.0 is going to be much much quieter than one that oscillates between -0.5 and 0.5.

Time Domain vs Frequency Domain

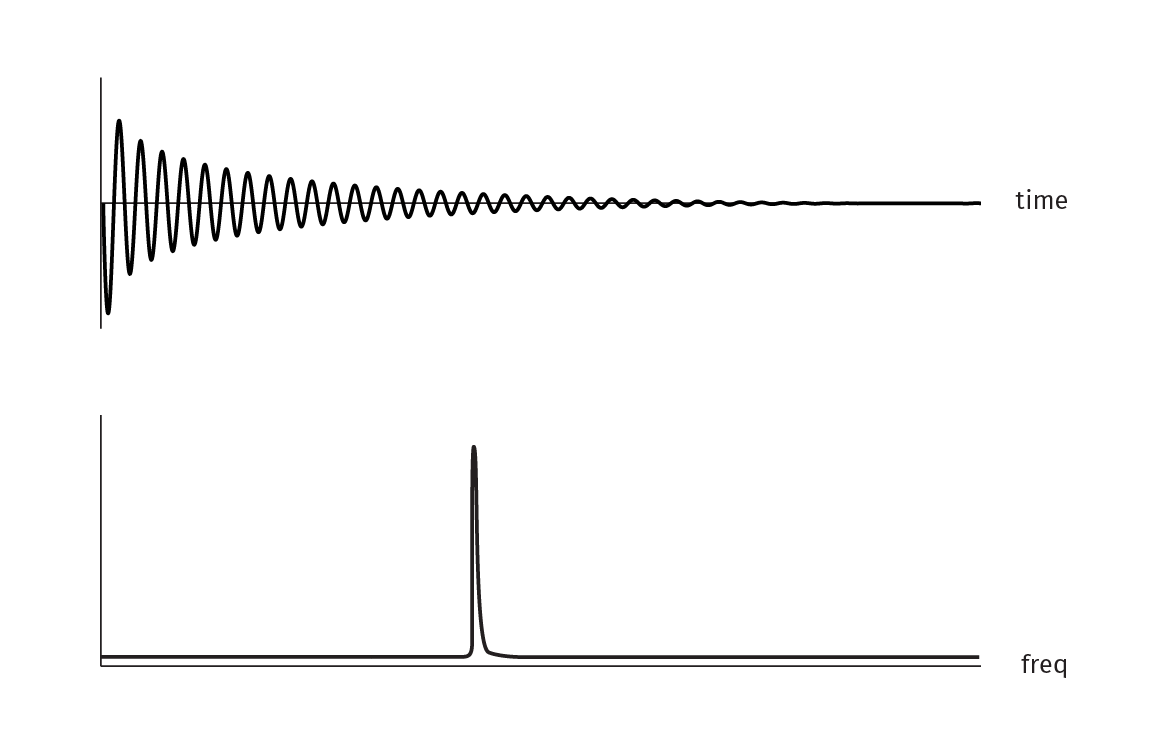

When representing sound as a continuous stream of values between -1 and 1, you're working with sound in what's known as the "Time Domain". This means that each value you're dealing with is referring to a specific moment in time. There is another way of representing sound which can be very helpful when you're using sound to drive some other aspect of your app. That representation is known as the "Frequency Domain".

In the frequency domain, you'll be able to see how much of your input signal lies in various frequencies, split into separate "bins" (see above image).

You can transform a signal from the time domain to the frequency domain by a ubiquitous algorithm called the Fast Fourier Transform. You can get an openFrameworks-ready implementation of the FFT (along with examples!) in either the ofxFFT or ofxFft addons (by Lukasz Karluk and Kyle McDonald respectively).

In an FFT sample, bins in the higher indexes will represent higher pitched frequencies (i.e. treble) and the lower ones will represent bassy frequencies. Exactly which frequency is represented by each bin depends on the number of time-domain samples that went into the transform. You can calculate this as follows:

frequency = (binIndex * sampleRate) / totalSampleCountSo, if you were to run an FFT on a buffer of 1024 time domain samples at 44100Hz, bin 3 would represent 129.2Hz ( (3 * 44100) / 1024 ≈ 129.2 ). This calculation demonstrates a property of the FFT that is very useful to keep in mind: the more time domain samples you use to calculate the FFT, the better frequency resolution you'll get (as in, each subsequent FFT bin will represent frequencies that are closer together). The tradeoff for increasing the frequency resolution this way is that you'll start losing track of time, since your FFT will be representing a bigger portion of the signal.

Note: A raw FFT sample will typically represent its output as Complex numbers, though this probably isn't what you're after if you're attempting to do something like audio visualization. A more intuitive representation is the magnitude of each complex number, which is calculated as:

magnitude = sqrt( pow(complex.real, 2) + pow(complex.imaginary, 2) )If you're working with an FFT implementation that gives you a simple array of float values, it's most likely already done this calculation for you.

You can also transform a signal from the frequency domain back to the time domain, using an Inverse Fast Fourier Transform (aka IFFT). This is less common, but there is an entire genre of audio synthesis called Additive Synthesis which is built around this principle (generating values in the frequency domain then running an IFFT on them to create synthesized sound).

The frequency domain is useful for many things, but one of the most straightforward is isolating particular elements of a sound by frequency range, such as instruments in a song. Another common use is analyzing the character or timbre of a sound, in order to drive complex audio-reactive visuals.

The math behind the Fourier transform is a bit tricky, but it is fairly straightforward once you get the concept. I felt that this explanation of the Fourier Transform does a great job of demonstrating the underlying math, along with some interactive visual examples.

Reacting to Live Audio

RMS

One of the simplest ways to add audio-reactivity to your app is to calculate the RMS of incoming buffers of audio data. RMS stands for "root mean square" and is a pretty straightforward calculation that serves as a good approximation of "loudness" (much better than something like averaging the buffer or picking the maximum value). The "square" step of the algorithim will ensure that the output will always be a positive value. This means you can ignore the fact that the original audio may have had "negative" samples (since they'd sound just as loud as their positive equivalent, anyway). You can see RMS being calculated in the audioInputExample.

// modified from audioInputExample

float rms = 0.0;

int numCounted = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < bufferSize; i++){

float leftSample = input[i * 2] * 0.5;

float rightSample = input[i * 2 + 1] * 0.5;

rms += leftSample * leftSample;

rms += rightSample * rightSample;

numCounted += 2;

}

rms /= (float)numCounted;

rms = sqrt(rms);

// rms is now calculatedOnset Detection (aka Beat Detection)

Onset detection algorithms attempt to locate moments in an audio stream where an onset occurs, which is usually something like an instrument playing a note or the impulse of a drum hit. There are many onset detection algorithms available at various levels of complexity and accuracy, some fine-tuned for speech as opposed to music, some working in the frequency domain instead of the time domain, some made for offline processing as opposed to realtime, etc.

A simple realtime onset detection algorithm can be built on top of the RMS calculation above.

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp {

// ... other members from audioInputExample ...

float threshold;

float minimumThreshold;

float decayRate;

};

void ofApp::setup() {

// ... the contents of setup() from audioInputExample ...

decayRate = 0.05;

minimumThreshold = 0.1;

threshold = minimumThreshold;

}

void ofApp::audioIn(float * input, int bufferSize, int nChannels) {

// ... the contents of audioIn() from audioInputExample ...

threshold = ofLerp(threshold, minimumThreshold, decayRate);

if(rms > threshold) {

// onset detected!

threshold = rms;

}

}This will probably work fine on an isolated drum track, sparse music or for something like detecting whether or not someone's speaking into a microphone. However, in practice you'll likely find that this won't really cut it for reliable audio visualization or more intricate audio work.

You could of course grab an external onset detection algorithm (there's quite a few addons available for it), but if you'd like to experiment, try incorporating the FFT into your algorithm. For instance, try swapping the RMS for the average amplitude of a range of FFT bins.

If you'd like to dig into the world of onset detection algorithms (and the larger ecosystem of what's known as "music information retrieval" algorithms), the Music Information Retrieval Evaluation eXchange wiki is a great source. On this wiki, you'll find the results of annual competitions comparing algorithms for things like onset detection, musical key detection, melody extraction, tempo estimation and so on.

FFT

Running an FFT on your input audio will give you back a buffer of values representing the input's frequency content. A straight up FFT won't tell you which notes are present in a piece of music, but you will be able to use the data to take the input's sonic "texture" into account. For instance, the FFT data will let you know how much "bass" / "mid" / "treble" there is in the input at a pretty fine granularity (a typical FFT used for realtime audio-reactive work will give you something like 512 to 4096 individual frequency bins to play with).

When using the FFT to analyze music, you should keep in mind that the FFT's bins increment on a linear scale, whereas humans interpret frequency on a logarithmic scale. So, if you were to use an FFT to split a musical signal into 512 bins, the lowest bins (bin 0 through bin 40 or so) will probably contain the bulk of the data, and the remaining bins will mostly just be high frequency content. If you were to isolate the sound on a bin-to-bin basis, you'd be able to easily tell the difference between the sound of bins 3 and 4, but bins 500 and 501 would probably sound exactly the same. Unless you had robot ears.

There's another transform called the Constant Q Transform (aka CQT) that is similar in concept to the FFT, but spaces its bins out logarithmically, which is much more intuitive when dealing with music. For instance you can space out the result bins in a CQT such that they represent C, C#, D... in order. As of this writing I'm not aware of any openFrameworks-ready addons for the CQT, but it's worth keeping in mind if you feel like pursuing other audio visualization options beyond the FFT. I've had good results with this Constant-Q implementation, which is part of the Vamp collection of plugins and tools.

Synthesizing Audio

This section will walk you through the creation of a basic musical synthesizer. A full blown instrument is outside the scope of this book, but here you'll be introduced to the basic building blocks of synthesized sound.

A simple synthesizer can be implemented as a waveform modulated by an envelope, forming a single oscillator. A typical "real" synthesizer will have several oscillators and will also introduce filters, but many synthesizers at their root are variations on the theme of a waveform + envelope combo.

Waveforms

Your synthesizer's waveform will define the oscillator's "timbre". The closer the waveform is to a sine wave, the more "pure" the resulting tone will be. A waveform can be made of just about anything, and many genres of synthesis revolve around techniques for generating and manipulating waveforms.

A common technique for implementing a waveform is to create a Lookup Table containing the full waveform at a certain resolution. A phase index is used to scan through the table, and the speed that the phase index is incremented determines the pitch of the oscillator.

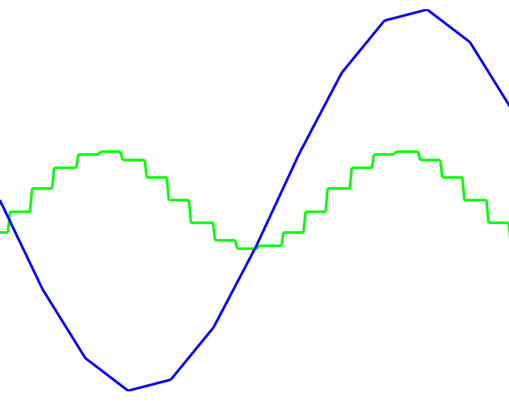

Here's a starting point for a synthesizer app that we'll keep expanding upon during this section. It demonstrates the lookup table technique for storing a waveform, and also visualizes the waveform and resulting audio output. You can use the mouse to change the resolution of the lookup table as well as the rendered frequency.

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp {

public:

void setup();

void update();

void draw();

void updateWaveform(int waveformResolution);

void audioOut(float * output, int bufferSize, int nChannels);

std::vector<float> waveform; // this is the lookup table

double phase;

float frequency;

ofMutex waveformMutex;

ofPolyline waveLine;

ofPolyline outLine;

};

void ofApp::setup() {

phase = 0;

updateWaveform(32);

ofSoundStreamSetup(1, 0); // mono output

}

void ofApp::update() {

ofScopedLock waveformLock(waveformMutex);

updateWaveform(ofMap(ofGetMouseX(), 0, ofGetWidth(), 3, 64, true));

frequency = ofMap(ofGetMouseY(), 0, ofGetHeight(), 60, 700, true);

}

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(ofColor::black);

ofSetLineWidth(5);

ofSetColor(ofColor::lightGreen);

outLine.draw();

ofSetColor(ofColor::cyan);

waveLine.draw();

}

void ofApp::updateWaveform(int waveformResolution) {

waveform.resize(waveformResolution);

waveLine.clear();

// "waveformStep" maps a full oscillation of sin() to the size

// of the waveform lookup table

float waveformStep = (M_PI * 2.) / (float) waveform.size();

for(int i = 0; i < waveform.size(); i++) {

waveform[i] = sin(i * waveformStep);

waveLine.addVertex(ofMap(i, 0, waveform.size() - 1, 0, ofGetWidth()),

ofMap(waveform[i], -1, 1, 0, ofGetHeight()));

}

}

void ofApp::audioOut(float * output, int bufferSize, int nChannels) {

ofScopedLock waveformLock(waveformMutex);

float sampleRate = 44100;

float phaseStep = frequency / sampleRate;

outLine.clear();

for(int i = 0; i < bufferSize * nChannels; i += nChannels) {

phase += phaseStep;

int waveformIndex = (int)(phase * waveform.size()) % waveform.size();

output[i] = waveform[waveformIndex];

outLine.addVertex(ofMap(i, 0, bufferSize - 1, 0, ofGetWidth()),

ofMap(output[i], -1, 1, 0, ofGetHeight()));

}

}Once you've got this running, try experimenting with different ways of filling up the waveform table (the line with sin(...) in it inside updateWaveform(...)). For instance, a fun one is to replace that line with:

waveform[i] = ofSignedNoise(i * waveformStep, ofGetElapsedTimef());This will get you a waveform that naturally evolves over time. Be careful to keep your waveform samples in the range -1 to 1, though, lest you explode your speakers and / or brain.

Envelopes

We've got a drone generator happening now, but adding some volume modulation into the mix will really bring the sound to life. This will let the waveform be played like an instrument, or otherwise let it sound like it's a living being that reacts to events.

We can create a simple (but effective) envelope with ofLerp(...) by adding the following to our app:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp {

// ... the same members as the earlier app ...

float volume;

};

void ofApp::setup() {

// ... the rest of setup() from before ...

volume = 0;

}

void ofApp::update() {

// ... the rest of update() from before ...

if(ofGetKeyPressed()) {

volume = ofLerp(volume, 1, 0.8); // jump quickly to 1

} else {

volume = ofLerp(volume, 0, 0.1); // fade slowly to 0

}

}

void ofApp::audioOut(float * output, int bufferSize, int nChannels) {

// ... change the "output[i] = " line from before into this:

output[i] = waveform[waveformIndex] * volume;

}Now, whenever you press a key the oscillator will spring to life, fading out gradually after the key is released.

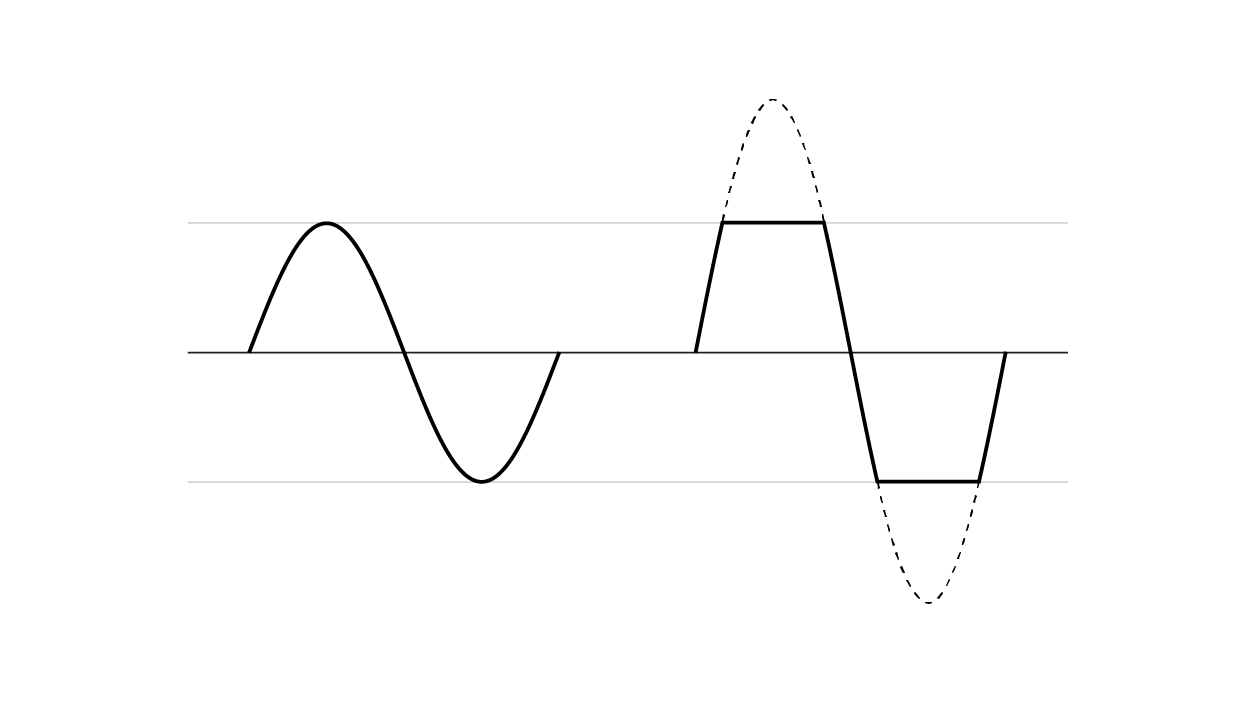

The standard way of controlling an envelope is with a relatively simple state machine called an ADSR, for "Attack, Decay, Sustain, Release".

- Attack is how fast the volume reaches its peak after a note is triggered

- Decay is how long it takes the volume to fall from the peak

- Sustain is the resting volume of the envelope, which stays constant until the note is released

- Release is how long it takes the volume to drop back to 0 after the note is released

A full ADSR implementation is left as an exercise for the reader, though this example from earlevel.com is a nice reference.

Frequency Control

You can probably tell where we're going, here. Now that the app is responding to key presses, we can use those key presses to determine the oscillator's frequency. We'll introduce a bit more ofLerp(...) here too to get a nice legato effect.

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp {

// ... the same members as the earlier app ...

void keyPressed(int key);

float frequencyTarget;

};

void ofApp::setup() {

// ... the rest of setup() from before ...

frequency = 0;

frequencyTarget = frequency;

}

void ofApp::update() {

// ... replace the "frequency = " line from earlier with this:

frequency = ofLerp(frequency, frequencyTarget, 0.4);

}

void ofApp::keyPressed(int key) {

if(key == 'z') {

frequencyTarget = 261.63; // C

} else if(key == 'x') {

frequencyTarget = 293.67; // D

} else if(key == 'c') {

frequencyTarget = 329.63; // E

} else if(key == 'v') {

frequencyTarget = 349.23; // F

} else if(key == 'b') {

frequencyTarget = 392.00; // G

} else if(key == 'n') {

frequencyTarget = 440.00; // A

} else if(key == 'm') {

frequencyTarget = 493.88; // B

}

}Now we've got a basic, useable instrument!

A few things to try, if you'd like to explore further:

- Instead of using

keyPressed(...)to determine the oscillator's frequency, use ofxMidi to respond to external MIDI messages. If you want to get fancy, try implementing pitch bend or use MIDI CC messages to control the frequency lerp rate. - Instead of "snapping" to the nearest sample in the waveform lookup table, try interpolating between neighbouring values to reduce the noisy artifacts a low-resolution lookup table produces

- Try filling the waveform table with data from an image, or from a live camera (

ofMap(...)will be handy to keep your data in the -1 to 1 range) - Implement a polyphonic synthesizer. This is one which uses multiple oscillators to let you play more than one note at a time.

- Keep several copies of the

phaseindex, and useofSignedNoise(...)to slightly modify the frequency they represent. Add each of the waveforms together inoutput, but average the result by the number of phases you're tracking.

For example:

void ofApp::audioOut(float * output, int bufferSize, int nChannels) {

ofScopedLock waveformLock(waveformMutex);

float sampleRate = 44100;

float t = ofGetElapsedTimef();

float detune = 5;

for(int phaseIndex = 0; phaseIndex < phases.size(); phaseIndex++) {

float phaseFreq = frequency + ofSignedNoise(phaseIndex, t) * detune;

float phaseStep = phaseFreq / sampleRate;

for(int i = 0; i < bufferSize * nChannels; i += nChannels) {

phases[phaseIndex] += phaseStep;

int waveformIndex = (int)(phases[phaseIndex] * waveform.size()) % waveform.size();

output[i] += waveform[waveformIndex] * volume;

}

}

outLine.clear();

for(int i = 0; i < bufferSize * nChannels; i+= nChannels) {

output[i] /= phases.size();

outLine.addVertex(ofMap(i, 0, bufferSize - 1, 0, ofGetWidth()),

ofMap(output[i], -1, 1, 0, ofGetHeight()));

}

}Audio Gotchas

"Popping"

When starting or ending playback of synthesized audio, you should try to quickly fade in / out the buffer, instead of starting or stopping abruptly. If you start playing back a buffer that begins like [1.0, 0.9, 0.8...], the first thing the speaker will do is jump from the "at rest" position of 0 immediately to 1.0. This is a huge jump, and will probably result in a "pop" that's quite a bit louder than you were expecting (based on your computer's current volume).

Usually, fading in / out over the course of about 30ms is enough to eliminate these sorts of pops.

If you're getting pops in the middle of your playback, you can diagnose it by trying to find reasons why the sound might be very briefly cutting out (i.e. jumping to 0, resulting in a pop if the waveform was previously at a non-zero value).

"Clipping" / Distortion

If your samples begin to exceed the range of -1 to 1, you'll likely start to hear what's known as "clipping", which generally sounds like a grating, unpleasant distortion. Some audio hardware will handle this gracefully by allowing you a bit of leeway outside of the -1 to 1 range, but others will "clip" your buffers.

Assuming this isn't your intent, you can generally blame clipping on a misbehaving addition or subtraction in your code. A multiplication of any two numbers between -1 and 1 will always result in another number between -1 and 1.

If you want distortion, it's much more common to use a waveshaping algorithm instead of trying to find a way to make clipping sound good.

Latency

No matter what, sound you produce in your app will arrive at the speakers sometime after the event that triggered the sound. The total time of this round trip, from the event to your app to the speakers is referred to as latency.

In practice, this usually isn't a big deal unless you're working on something like a musical instrument with very tight reaction time requirements (a drum instrument, for instance). If you're finding that your app's sound isn't responsive enough, you can try lowering the buffer size of your ofSoundStream. Be careful, though! The default buffer size is typically the default because it's determined to be the best tradeoff between latency and reliability. If you use a smaller buffer size, you might experience "popping" (as explained above) if your app can't keep up with the extra-strict audio deadlines.